Final Space, Kid Cosmic, and the complication of space adventures

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Television, Writing on September 20, 2021

Final Space ended its run after three seasons, and honestly, it was to be expected. The ratings for the third season were down rather significantly. While the marketing didn’t really do the show any favors, it was particularly telling how no one across social media seemed to even praise the animation of the show (which continues to be incredible), let alone the show overall. It’s on Netflix now, and there’s a chance that new viewers will latch on the show via binging, arguably a better way to watch the show than week-to-week, and garner so many hits that some kind of finale–weather a season or a movie–could be commissioned. I have my doubts though.

Final Space has been both amazing and frustrating to watch, a rare expansive (and expensive) show of incredible visuals and moments of epic dramatic scale, that nevertheless just could not focus. Final Space feels like the ur-example of the importance of how simply “pacing” can make or break a show. Because Final Space had it all: compelling characters (with perhaps the exception of the lead, but more on this in a second), an escalating set of stakes; a juicy, constantly evolving plot; raw, shifty villains; eye-popping animation, rich themes; and, uh, humor. That last point, as you can see, I hesitated on, because comedy, beyond all that has been mentioned, is wholly dependent on timing and pacing, and because Final Space struggled at pacing overall, a majority of the jokes and humorous moments fell flat.

It’s hard to describe without watching Final Space and seeing the attempts at jokes in action. Generally speaking, the humor was split between “characters with funny voices talk in funny ways” and that kinda of improv-y, stammering humor that seems to be all the rage now. It could be funny, if only because it was inevitable that a certain line reading or a particular reaction would garner laughs, but it was difficult to describe the show as comedic. The scale of Final Space’s dramatic beats were so high that it often became impossible to pull back to make a jokey bit work, and no amount of exasperated reactions and belabored metaphors could really make Gary comedically sharp enough to carry the show the way its creators probably expected. Gary’s most memorable moment across Final Space’s three season had nothing to do with “cookies,” but the brutal, emotional fight between him and Avocato over the truth about Lil’ Cato’s parentage.

In fact, the bits about the cookies are a good example of Final Space’s comedic struggles. Many early jokes wrap around Gary trying to acquire a cookie that’s always out of reach, with increasingly nonsensical obstacles getting in his way, but what isn’t clear is if Gary even likes cookies, or if he just wants one. “Cookie” is a funny sounding word, too, with it’s hard ‘K’ sounds and humorous tints when spoken fast and kind of high-pitched. But it wholly separated from Gary as a character and certainly separated from the intensity of the show, and its clear why this specific joke gets a nigh mention in its third season.

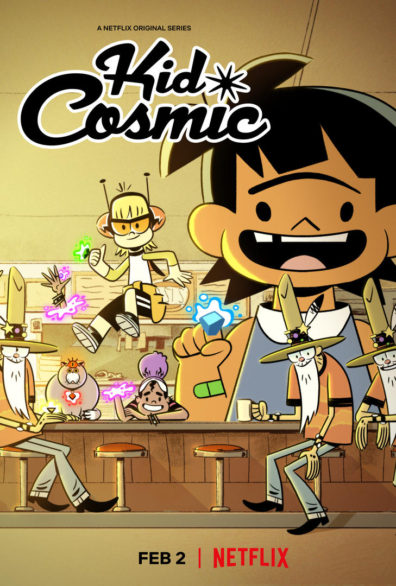

It’s somewhat interesting to compare this show to Kid Cosmic, Craig McCracken’s cracking Netflix series, also about a group of ragtag “nobodies” facing increasingly dire, astronomical dangers. Both shows are clearly aiming for different audiences, but both shows also struggle with squaring its world-ending stakes with its snappy, funnier moments. McCracken, to be clear, is much better at it than Olan Rogers, but I do think the second season goes so far, again, into viciously high stakes that comedic moments feel forced, or leave its characters acting dumber than usual. There is no logical reason whatsoever for Jo to force her team to celebrate at a party filled with bad dudes, after just barely completing a nearly-blown heist from that same party. Jo struggles with tempering her expectations and behaviors as she learns how to be a leader, and forcing “co-workers” to celebrate has the thematic groaner energy that feels familiar and relatable, but to do so at the party you just infiltrated (and almost botched) is an Archer bit of idiocy; sure, it works for that show, but it comes across too dumb here. (I think this episode is meant to arouse suspicion with Queen Xhan, as she is familiar the leader of the villains here, and she’s the one who convinces Jo to celebrate among the criminals they just fleeced, but not only she not a traitor, that red herring leads nowhere else.)

And then there’s the stories of each of these shows, the narrative concocted in order for these shows to reach these dramatic highs. Sci-fi space, with its infinite, unimaginable vastness and the made-up jargon and tech that allows for more made-up adventures and travel within it, requires a deft, comfortable hand in maintaining a clear narrative to follow, to understand what the characters are doing, and why. (The final season of Voltron absolutely gets lost in the weeds with its own lore, becoming a robot-smash, shout-fest of nonsensical terms). The characters in Final Space actually reach Final Space, and I still don’t know what “Final Space” is. Earth is also destroyed twice? I mean, I don’t really need to know the details; I know full well I can do a deep dive into the wikis, or a re-watch, and “figure it out”. It’s really more a matter of character needs and goals, and the specificity of what’s needed, and what obstacles are in their way, and why. That gets muddled pretty fast, and perhaps ten episodes weren’t enough to slow things down to Explain Things and What It All Means, and plopping some riffs with poor comedy here and there made things worse, not (in terms of escapist reprieves) better.

Interestingly enough, Kid Cosmic had the opposite issue, where not even eight episodes, one of which didn’t even crack the fifteen minute mark, possessed enough “stuff” to fill them all. (Which is weird, because you’d think the search for thirteen Rings of Power would have sorts of narrative potential.) There’s a bit of a slag in the middle of the run, which includes a baffling flashback opener of ring acquisitions and losses. Often, character decisions feel more like they’re made for thematic purposes over narrative ones (Jo joining a battle royale just to “prove herself” comes across as silly, regardless of how depressed and down she’s feeling). The escalation what it means to be a hero, and the choices that heroes have to make, is rich thematic fodder but gets muddled when they become prime motivations instead of the specific choices that are needed to solve current narrative problems. (This is kind of a long way around to say it probably would have made more sense for Jo to join that battle royale alone if she noticed the ring of power in Krosh’s eye from the TV commercial; as it stands, Jo yelling “character notes” about proving herself in the midst of battle is kind of sloppy, even in a “kid’s” show.)

And to be clear, both Final Space and Kid Cosmic are filled with rich, powerful moments that, in isolation, are worth it. But these moments often dramatic trees, scattered about a semi-empty field of narrative, crooked branches and comedic weeds. (Gary’s forced, belabored metaphors are rubbing off on me.) Part of me thinks that the rushed schedules of animation is starting to really filter down into the production of these shows, providing less time to really work through the ins and outs of certain plot points or the overall story. Regardless though, both shows never quite could sink its teeth into the universe that it established. I like what I see, but I can never love it.

Still working through how best I want to handle blog posts, I think I’m going to update every two weeks now (which gives me time to work on other projects), and I’m not going to provide summaries or outlines on what I’m gonna write next, because really, it’s all based on what mood strikes me and what I happened to have watched or what I happen to think about at the moment!

Hilda and its Mom Problem; Spy Racers and Camp Cretaceous puts in the work

Posted by Admin in Animation, Television, Uncategorized, Writing on August 30, 2021

Hilda has a ton of promise as show, although it’s “third season” will be a movie instead, presumably about the fallout from the ending of the second season, which left Hilda in a body-switch scenario with a troll. It’s a pretty fraught storyline in which to end a season, especially after a season in which Hilda and her mother fought and struggled to make bonds or connections that used to come so easily to the two. They were quite the unit at the beginning of season one–the two of them living alone in a cabin in the woods, all filled with wonder and magic and near-infinite space for exploring and adventure. When they had to move to the city (their cabin was destroyed by a giant!), there was a bit of mother-daughter conflict, mostly due to Hilda’s prickly response to city-living and friend-making. But Hilda’s mom quickly showed her daughter that not only did the city possess a huge number of opportunities for adventure on its own, but that she herself knew her away around them. It was the show’s small but notable way of showcasing a strong parent-sibling bond in the face of the kind of craziness that could break them–and, by avoiding the trope of parents being unfamiliar with or ignorant of the weirdness around them, pulls its adult characters into the delightfully audacious imaginations of their children: everyone is apart of this world and has to deal with its antics equally.

So it was kind of a shock when Hilda began to exhibit alienating, and even hostile, anger at her mother throughout season two. It seemed quite a strong counter to the connection they held in season one. There’s a very specific, narrow thread to Hilda’s determined stubbornness, which can be frustrating to other people not quite attuned to it (this, in fact, causes a big blow up between her and Frieda in season one, a conflict that might require two or more watches to get.) But after watching all of season one and seeing how Hilda’s mom seemed totally on board with Hilda’s behavior, and how Hilda’s respect for her mom was so ingrained, watching her suddenly show flashes of attitude at her mom seemed so sudden and… weird. The show tried to thread this shift in Hilda’s demeanor by giving her a deep seated anxiety that had her worried that she was becoming too “naughty” with all of her antics. But it makes little sense. Season two Hilda wasn’t more or less “bad” than season one Hilda, and, again, her voracious outgoing energy has been, time and again, embraced by her mom (give or take the general concern/love/desire for safety that’s normal for any parent.)

There is, arguably, a dramatic, emotionally-rich narrative in which a young but maturing girl starts to question their status under her parent’s roof, that the hormonal and emotional changes that come with puberty and growing up might trigger confused, conflicting reactions to the rules and structure that, not long before, was accepted and tolerated. Hilda suddenly bristling at her mother’s… everything could have worked if Hilda’s encounters began to trigger new, confusing feelings within her. Maybe the moody, ghost-esque teens suddenly begin to look more appealing, or there’s a cute boy (or girl) that slowly begins to catch Hilda’s fancy. There is a potential maturation tale in which Hilda dabbles with witchcraft–although that’s mainly with Frieda, the career-defining vibe to this particular story suggests falling into an adventure-filled “job” that Hilda may want tackle sans parental helicoptering. But we never get that, not even in the narrow, nuanced ways in which Hilda usually functions (the only clue we get is a new, slightly weird post-credits song that “Hilda” sings about her struggles with her stubbornness, which kind of feels weird and desperate, a last-minute Hail Mary method to clarify Hilda’s new emotional responses since that never really happens in-show). Hilda thrives with potential, and that new struggle with her mom could have been as complex and well-handled as Steven’s post-war trauma in Steven Universe Future. But it was never meant to be; perhaps the next movie can put in the tricky, ret-con-y work to plug those daughter/mother dilemmas.

One thing I like about Fast And Furious: Spy Racers? It’s efficiency. Every season is eight ridiculous but snappy episodes that roll in, do their thing, and roll out. There’s no real commitment to the cast, theme, or story here–just fast vehicles doing crazy stunts. The jokes are dumb and forced, but everything moves at such a fast pace that nothing really sticks around long enough to be bothersome, save for a few exceptions (one second season villain, a bad parody of a Real Housewife/Instagram influencer, wears out her welcome upon returning in the third season; the Sahara season is boring because, well, racing in deserts is boring, and it drags pretty heavily).

It, and its “spiritual” counterpart, Jurassic World Camp Cretaceous, both star groups of kids in scenarios that shouldn’t star groups of kids. But both have just enough winking energy to let it roll off your shoulder. Camp Cretaceous is a lot more “grounded” than Spy Racers, in that those kids are way more defined and “realistic,” and have a much more tighter familial connection than Spy Racers hilariously throw-way “we’re family” vomit. But neither is particularly necessary; if your kids like cars and/or dinosaurs, then they’re gonna watch them. Still, shows like these are worth at least exploring once, I think, because of their efficient, workman-like approach to knocking out a season of action, drama, interpersonal conflicts, and broad, cheesy humor. At their peak, both shows can provide an episode that fires on all yeoman cylinders, a thrilling 22-minutes that almost, almost, capture that respective franchise’s best, most enjoyable moments. For Spy Racers, it’s an absurd chase between a submarine and a jet bent on destroying said sub. For Camp Cretaceous, it’s a dinosaur/kids chase within tight quarters and rickety elevators, echoing the high thrills of the OG Jurassic Park. These moments are rare and perhaps not worth wadding through so many seasons of off/on entertainment, but it shows that there’s value in shows that “do the work”.

Spy Racers thrives on bombast and nonsensical cutting edge tech, which works better than some of the stunts that the show comes up with–despite being animated, and thus able to fudge the physical possibilities of vehicular assault more than its live-action counterpart, a lot of the car action is rather bland. Because the show operates at eleven and goes from there, it’s impossible to really come up with something truly visually exciting, since… all of it is, really. And yeah, the characters are broadly drawn and too ridiculous to really engage with them. Which means that they’re perfect for everything the show is putting down. Camp Cretaceous, on the other hand, sinks its teeth into its characters, which is impressive, but arguably can go too far in this direction as well. Mining these characters for layers of nuance to otherwise create more interpersonal conflict is fine, but two characters’ choices in that show’s most recent season bordered on flat-out stupid. (Three episodes are spent dramatically hyping up one kid’s fervent desire to live on the brutal dinosaur island, only for him to obviously change his mind in an instant; one kid sudden sullen attitude towards another kid and his questionable but effective plan comes out of nowhere). Workman animated shows can be good for bumps of audio-visual sensory pleasure, but they tend to lose steam in the long run, whether trying to find more heart-pounding stunts, or scratching at the bottom of the character barrel to contrive yet another fight between characters who, by now, ought to know better. (Spy Racers just dropped its fifth season; I can’t see them going beyond seven.)

I know I said I was gonna do Looney Tunes today as well, but I’ll have to save that for later, as an emergency writing project jumped in my lap. I’m going to be away for Labor Day weekend, so I probably will tackle that show, as well as I Heart Arlo, by September 13th. I also want to discuss the… “scourge” of the generic adult animated show. (I’m a patient man who always tries to let cartoons be the way they are, but even I’ve been growing weary of the “look” of them.)

Centaurworld and The Bad Batch excel in animation but struggle with narrative

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Television, Uncategorized, Writing on August 23, 2021

At the very least, Centaurworld is a visually rich piece of animation. In some ways, the fluidity and elastic movements of a lot of the action and expressions are better than the sharp, cinematic quality of Green Eggs and Ham, itself a fine show that probably would have worked as a movie than serialized programming. Centaurworld has a fine handle on its goofier moments, of explicit closeups and elaborate dance moves, in nifty montages and explosions of color and effects that draw the viewer eye and helps to, perhaps, ease audiences more prone to shy away from the specific and weird character designs themselves. Horse and Rider are the traditionally animated figures of the show; the centaurs of Centaurworld are what if the bubble-designs of Steven Universe would look like if forced into a Day-Glo, Laffy-Taffy machine, and it’s remarkable how the animators are able to bridge those stylistic differences so smoothly. Horse, mostly hard, sharp lines, ends up screaming and singing in silly, exaggerated, squash-and-stretch ways, and damn, it somehow works.

The story that’s told across the ten episodes of Centaurworld, however, is pretty undercooked. I started to get a bit hyped for the show when it got a bit of push on social media–a lot of talented animators, writers, and musicians worked on the show, and their words suggested something quite special. The trailers and the publicity photos also suggested something layered (if not quite new): similar to AdventureTime, the candy-coated universe of Centaurworld was something of a cover, or a mask, or a distraction, to the secondary, bookended “real” world where war thrived and lives were lost.

It’s not that. Well, not exactly. Honestly, I can’t quite put my finger on what Centaurworld is, exactly, both in the narrative/settings sense and in the broader, “what is this show even about” sense. It’s a fine show, but I found it somewhat messy and fairly… incomplete. Similar to The Owl House and Star Vs. and Amphibia and The Dragon Prince, shows with huge worlds and stringent lore and copious amounts of backstory, it all yet feels like a lot of the actual plot is being made up on the fly. There’s only two significant story reveals that occur during the course of the season, and while there are smaller flashes of dramatic narrative that pop up, they happen awkwardly and haphazardly. Centaurworld is too caught up in its “all-encompassing-ness”–in its absurd characters, its padded joke-telling, its weirdness. It has tons of confidence in its characters as entertaining weirdos being weird at each other, but they’re not exactly deep, so the premise is based whether you get a kick out of their antics. Comedy is subjective, so maybe there’s a ton of people who love these oddballs, but as avatars guiding us through this whole new world, they’re lackluster.

Kipo and the Age of Wonderbeats understood it had to clarify its new world first and foremost, to establish the rules, the boundaries, the obstacles that define it. Centaurwold doesn’t. It starts to, but then, I believe, assuming it could do the bulk of that next season, kind of just fucks around. It’s non-Horse cast contorts in weird ways and say very oddball things in very oddball ways, and they trail off or stammer around awkward moments, and they provide creepy expressions as the camera linger on them in extreme close-ups. They can “shoot miniature versions of themselves out of their hooves,” miniature versions who scream and panic because they suddenly exist and can’t handle it, a well that Rick & Morty has all but tapped dry. Centaurwold has the vibe of a Youtube poop mixed with those streaming videos cut so erratically that you can’t quite tell what the joke is, all while forgetting to clarify or develop the characters through that chaos. Horse and Ched bicker a lot, but for the life of me I couldn’t understand why they hated each other; their argument pops up in one episode randomly because, I guess, it sounded funny when they bicker? Durpleton, at one point, gains the ability to fart-verbalize validating compliments, implying that he’s never received that from his father, but the show never unpacks that (they even joke about not unpacking that) and it’s prolonged for so long with no real payoff.

There’s an episode where the characters find themselves in a world that’s a parody of Cats, in which the Cat-taurs compete to win a special sash (which also has a McGuffin they need). Zulius, the showy, stereotypically flamboyant of the group, has history with this competition (he constantly loses it), falling into exaggerated, depressed tantrums before attempting to coach Horse through it. This is pushed as important, revealing backstory (again, they make a meta joke about this) but it never answers the most obvious question: how and why did Zulius, who’s not a Cat-taur, even get so caught up in this very clearly cat-taur-only competition? The episode doesn’t say, and to be honest, it probably could get away with these non-deep deep reveals if the very second episode didn’t provide an extremely, genuinely fraught history with Wammawink. That narrative set up expectations for more fraught or informative reveals in future episodes, but none of them occur.

Centaurworld is ultimately a Weird Cartoon masking as a layered, Steven Universe/AdventureTime one, with the violent backstories, mythical architecture, mysterious characters, and unique iconography never truly being explored. (There’s an implication that the Nowhere King, the show’s Big Bad, and the nameless purple-haired human had a similar bond like Rider and Horse, a bond that in some way caused much of the chaos happening now, but in no way is that explained). The extremely dark narrative of a whale shaman ending the existence of travelers deep in depression is ruined by an obvious sign that literally explains this that somehow everyone missed. It’s the kind of bit that in a lot of ways sums up Centaurworld. Here’s hoping there’s richer, deeper rewards in the second season.

The Bad Batch, on the other hand, probably would have worked better with a lean ten or twelve episodes. It’s an excellent exploration of the aftermath of Order 66, the trigger that called forth the clones to kill all the Jedi in their vicinity. It’s a fascinating, overlooked part of the Star Wars saga, and it’s great to have a in-depth, close look at that transition from Republic to Empire. It does this by focusing on the Bad Batch, a group of clones immune to Order 66 (kind of) and action-heavy stars of average-at-best arc on The Clone Wars.

It was, at the time, odd to see the follow-up to The Clone Wars focus on this team of semi-superpowered clones. (Really, it’s the follow-up to Star Wars Resistance, a show so bad that it’s likely we’ll never see cameos from any of that show’s cast pop up elsewhere.) The Bad Batch, too, is an animated, visual tour-de-force; if the hard-edged, plasticky character models aren’t in the frame, you would swear you were watching live-action. Trees and mountains look lush and full; water effects and weather patterns are massive and dynamic, and explosions and debris damn near burst from the screen. The Bad Batch even ups its visuals by playing around with film trickery, with flashes of focus shifts and whip-pans. The score, too, is rich, bold, and loud: even without surround sound or a subwoofer, you can feel the throbbing bass in your living room or within your headphones.

But again, sixteen episodes is a lot, and like Dave Filoni’s other animated shows, it often struggles to pad out enough material to fill it. Newbie clone (of sorts) Omega, her with the sharp Kiwi accent and the precocious energy, isn’t as much as a distraction as one might suspect: she’s sharp on her toes and rather resourceful, but not so much so that she can escape every scrape that absolutely would require a trained soldier. The Bad Batch mostly struggles through prolonged filler episodes of bounty hunting for Cid (long after they financially escaped her leash) and Filoni’s overwrought penchant to bring in cameos galore (Hera, Saw, Cad Bane, [lady from Mandalorian]. None of the episodes are in any way bad, but seeing this group of mercenary soldiers talk around the same points over and over gets a bit tedious. Dee Bradley Baker voicing five different clones so distinctly and credibly is some kind of miracle; only if the writers could push those characters individually on paper a little harder, The Bad Batch could spend more time developing them specifically instead of broad, stylistic, skill-based ways. What makes them really tick? I hope we get that sooner instead of, like, the six or so episodes before the show’s series finale, like Star Wars Rebels.

Next week I might spill a few words about the silly, rip-roaring The Fast and The Furious: Spy Racers, and allow me to gush about why, finally, they finally figured out Looney Tunes. If I have time/space, I may also shed a few words about some past past animated shows I’ve caught: Hilda, perhaps?