Archive for category Television

Tumblr Tuesday – 09/17/13

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Comics, Film, Television, Video Games, Writing on September 17, 2013

After a two-week hiatus, Tumblr Tuesday is back! Not a ton of stuff, but there’s a few goodies:

— I wrote a little about the DC Comics contest concerning a suicidal Harley Quinn:

http://totalmediabridge.tumblr.com/post/60849576709/dc-contest-on-harley-quinns-suicide-is-telling

— I hate Makorra. The season premiere of The Legend of Korra only solidified my hate:

http://totalmediabridge.tumblr.com/post/60852296524/legend-of-korra

— Speaking of which, two gifs from Avatar depict the “humor” in that show’s fight sequences that Legend of Korra’s action sorely lacks:

http://totalmediabridge.tumblr.com/post/61027731906/meehighmeelo-unwinona-i-love-that-aangs

— A link to a link satirizing the “brooding male anti-hero” that dots the landscape of television’s Golden Age:

http://totalmediabridge.tumblr.com/post/61050549524/men-be-brooding

— And 16-bit versions of modern 3D games, and they look awesome:

http://totalmediabridge.tumblr.com/post/61051131873/pxlbyte-modern-games-get-demakes-games-of

CHILDHOOD REVISTED – TaleSpin

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Childhood Revisited, Television, Writing on September 16, 2013

TaleSpin isn’t really a kids show. It’s a show for adults to relive their childhood. How TaleSpin channels the pulpy, ten-cent serials of the 30s to introduce kids to what their parents enjoyed.

A friend of mine bought a broken 78-player. He fixed it up, acquired some records for it, and proceeded to play them as we sat around and sipped scotch and beers. The sound and style recently became popular due to games like Bioshock, Bioshock Infinite, and Fallout 3 – games that explore the extreme, uncomfortable sides of eras long gone. In them, these classic songs, played at various intervals, often go against the disturbing chaos around them, a quiet sense of sanity and clarity in a world gone mad and violent. Also, they’re just pretty damn good – my favorite song so far? Tony Pastor’s “Meet Me At No Special Place.”

That’s the hidden specialness of those games – they’re essentially “updated and modern” takes of various adventures that hundreds of thousands of kids would read for ten cents at their local bookstore or magazine stand. Authors tossed out tales of grand adventures, remarkable robots, grandiose superheros, hidden temples, mad scientists, rugged adventurers, cunning shamuses, and so on. These led to comics, then radio shows, then movies, then influenced modern films like Indiana Jones, Sky Captain, The Shadow, and even Star Wars.

TaleSpin, in perhaps the most boldest decision in cartoon history, sought to bring back the tone and style of those serials through the use of talking animals, many of which were from The Jungle Book. If Darkwing Duck was unique in its willingness to go wacky and silly, TaleSpin was its complete opposite, more prone to go serious, in the adventurous, pulpy sense. Unlike Darkwing Duck, characters could theoretically be killed in this show. There are shoot-outs, airplane fights, shady businessmen, and ruthless gangsters, all couched in a comfortable, fun, campy spirit so things don’t get too grim. And in the center of it all are the well-meaning but essentially morally grey characters of Baloo, Rebecca, and Kit.

TaleSpin – (1990)

Director: Larry Latham, Robert Taylor

Starring: Ed Gilbert, Sally Struthers, Jim Cummings

Screenplay(s) by: Jymn Magon, Libby Hinson, Lee Uhley

To prepare for this review, dear readers, I watched the entire 21-episode, 1-season run of Tales of the Gold Monkey, the show TaleSpin is loosely based on. Wildly popular since it debuted after Raiders of the Lost Arc, Tales, a 1985 show with a 1938 setting, style, aesthetic, and sensibility, starts off interesting but slow, pushing into dangerous racially-uncomfortable territory. But Donald Bellisario (creator of Quantum Leap) rightly focuses on the characters and their history/pasts as the show goes along. It isn’t perfect – Sarah White really gets the short end of the stick in terms of development, and Jack, the one-eyed dog, is kinda lame no matter how much you slice the camp pie – but I definitely enjoyed the change and more serious direction towards the end of its run. CBS didn’t agree, desiring more outlandish tales involving wild natives and wacky Nazi’s, and the studio and Bellisario clashed over the show’s direction, inevitably leading to its cancellation despite high ratings. I can’t say I agree with either side: Bellisario’s direction was necessary, but it wasn’t as if the later episodes weren’t silly enough (Hidden bombs on ships! High-stakes poker games! Crazed prophet predicting wild weather!). But I enjoyed it for what it was, and it’s clear where TaleSpin draws inspiration, cribbing names and ideas liberally from its source. TaleSpin also managed that perfect balance between serial tales and rich characterizations, focusing on the lives of three people: Baloo, Rebecca, and Kit.

There aren’t any heroes in TaleSpin. Sure, Baloo, Rebecca, and Kit are the show’s protagonists, but to say they are heroic would be wrong. They’re three people who in some ways are forced to be together in order to get through the times. As the backstory goes, Baloo, ace pilot but otherwise lazy scumbag, loses his air delivery business after failing to actually pay the bank. He is bought out by Rebecca Cunningham, an extremely smart but internally desperate woman, who hires him as his pilot. Kit Cloudkicker comes along as an air pirate who has no aspirations to be an air pirate, and through a truly great and exciting four-part series, “Plunder and Lighting,” ends up as part of the crew.

“Plunder and Lighting” is a fantastic introduction to the series, really working to set up the principal cast and their quirks, weaknesses, and strengths. We meet the mechanical prodigy but moronic Wildcat, the party-loving Louie, the sinister and dangerously brooding Shere Khan, and – I do not exaggerate when I say this – animation’s best character ever, the self-centered but genuinely vicious Don Karnage (I will get into him in bit.) These episodes introduces the variable tone of the show, which can be light and fun, comic zaniness, or perilous and dark. Pulling from its expansive pulp origins, TaleSpin weaves a rich set of tales that make the characters and world of its show come alive.

And TaleSpin feels alive. The various settings within the show – Cape Suzette, Thembria, the cliff guns, and the various exotic locales – are wonderfully, brilliantly designed, vibrant with its own energy and sense of culture. I feel like I could wake up in Cape Suzette and find my way from Hire for Higher to Khan Industries and not get lost. TaleSpin marvels with its detailed locations, willing to show both the upper class, middle class, and lower class of almost every place they visit. We see the luxurious office of Shere Khan, the cluttered, wooden office of Rebecca Cunningham, and the shady, slim alleyways of Cape Suzette. That in itself is bold in its sheer audacity – very few animated shows would put in that kind of detailed, layered work.

Even while the setting is top-notch, the characters are top-notchier. Characters possess clear-cut strength and weaknesses, flaws and quirks, moments of brilliance mixed with moments of sheer stupidity. Even one-off characters that pop in and out have history and purpose. They’re not just animated joke machines. They feel real and relatable. They don’t “change” per se – I wrote over on my tumblr how characterization works differently in animated cartoons – but through their set personalities we discover the core of these characters, their goals, and their constant failures.

There are essentially three types of episodes. There are “pure adventure” episodes, tales that could be pretty much ripped from the serials themselves, re-written to accommodate the show’s setting. They’re the most mysterious, weird, and exciting, with secrets and magic and wild technology and hidden rooms and undiscovered kingdoms. There are “comedy of errors” episodes, in which the characters try to do something ill-advised or poorly planned, and end up in a ridiculous situation that’s more funny and cute than anything else. And there are “character episodes,” episodes that delve into the characters and reach something deep and powerful, exposing something about themselves or their relationships to each other.

“Polly Wants a Treasure” and “For Whom the Bells Klangs” both are examples of the adventure tales. The former has Baloo and a talking parrot constantly arguing as they and Kit work to stay one step ahead of the air pirates searching for a treasure. The two-part “For Whom the Bells Klangs” is a desert-spanning adventure where Louie and Baloo reluctantly spar with a Tim Curry-voiced snake while making goo-goo eyes at an attractive archeologist fox, all over the legend of the Lost City of Tinabula. The adventure tales usually have two characters conflicting over minor shit while being up against unknown or mysterious forces. They’re exciting enough, but only really stand out when the interplay between all treasure-hunting parties are at their best. Comedy of error episodes include, “The Golden Sproket of Friendship,” (a wacky run-around between Baloo/Kit, Thembrians, and a couple of goofy gangsters over a tiny gift to Cape Suzette) “Vowel Play,” (Baloo’s poor spelling skills are used against him by a couple of “clever” gangsters) and “Your Baloo’s in the Mail” (A Rat Race-esque romp where Baloo and Kit have to assist a bunch of slow-ass mailmen to their final destination to win a contest.) And the character episodes, the most dramatically powerful ones, include “Her Chance to Dream,” where a lonely, overworked Rebecca comes dangerously close to leaving her complex life behind for peace among the clouds with a ghost – and almost leaving behind her daughter. “The Old Man and the Sea Duck” gets into Baloo’s psyche when he has to relearn flying (and more importantly, loving to fly and having confidence in flying) after suffering from amnesia. And “Paradise Lost” gives Wildcat his moment, when, in order to protect his new-found dinosaur friends from evil hunters, stops the flow of magic water that gives birth to the pre-historic setting. It sounds silly until you realize how lonely a guy like Wildcat really is; no one can really relate to him and his simple pleasures except animals, so to see him make that sacrifice is heartbreaking (also, they actually show an dinosaur getting shot).

The best episodes are the ones that really can balance all three episode-types with some wonderful animation and top-notch writing. In “From Here to Machinery,” Baloo competes with robot pilots to determine the future of mortal pilots employ. He fails (due to being unable to stay awake) and robots win, sending all pilots out of a job. When the robot pilots refuse to change directives during a lighting storm, though, Baloo flies in to save the day. It’s definitely cool to see the sleek, “World of Tomorrow” design of the various robots, but it’s nice to add the dramatic undercurrent of Baloo’s vulnerability. He is a confident, extremely talented pilot, bordering on egotistical, but when he fails at flying, it’s heartbeaking to see him all depressed. Flying is literally the only thing he knows, and it’s really great that they’re dedicated to this – “Vowel Play” and “Sheepskin Deep” showcase Baloo’s lack of an education, his efforts to reform, and implies that education is just as important as experience (which ran counter to the sheer onslaught of educational cartoons that were out there).

“Citizen Khan” is arguably the best episode of the entire show, blending character, adventure, and erroneous comedy into a nice, meaty plot. A couple of corrupt “lawmen” shoot down the Sea Duck, only to be revealed as miners who took over a Khan Industries mining town that Shere Khan failed to follow up on. Add in some forced indentured servitude, explosive minerals, a bit of mistaken identity, a couple of minors hell-bent on taking out Khan, and whether Khan himself will discover this mini-coup, and you have a really tense, fun, intriguing episode here, filled with great lines, great animation, and a real sense of isolation and locale. From a narrative standpoint, it’s TaleSpin at its best.

From a character standpoint, however, I cannot stress enough how utterly amazing Don Karnage is. He’s something of an revelation, really: a fantastic villain defined deliciously by his pride, his ego, and his incredible discordant use of language. Jim Cummings is at his vocal best here, reportedly inspired by I Love Lucy’s Desi Arnaz for the accent. It’s really difficult to capture the vocal readings in print, but Cummings take on lines like “Now, do not forget to remember!” and “Congratulation! You have not done a terrible job!” are just perfect. Karnage himself makes a great villain because despite being somewhat goofy and surrounded by morons, he himself is rather vicious, conniving, and cunning – he worked both with AND against Shere Khan, he plotted the entire attack on Cape Suzette in “Plunder and Lighting,” and he set up a really clever trap in “A Bad Reflection on You.” He even has a sense of honor – there’s a subtle but telling moment in “Stuck on You” where Khan gains the upper hand in a fight with Baloo, leaving the pilot dangling off the end of the Sea Duck. Before Karnage sends him to his death, Baloo calls him a coward and tells him to get it over with. In an ironic twist, Karnage actually saves him! When Baloo mentions this, Karnage responds, “I know – I don’t know what came over me,” and immediately goes back to attacking the bear. This great piece of nuance might be lost to kids, but Karnage, given the opportunity to finish off Baloo, failed to do so because deep down inside he believes in honor among thieves – or, in this case, killing. Honor and keeping one’s word is the perfect theme to “Stuck on You,” and it plays nicely and subtly throughout the episode.

While I had to take a moment to give Karnage his own paragraph, I can’t sell the rest of the cast short. I spoke about Baloo at length – a great pilot but lazy otherwise – but Kit is a fun character, not too annoying and a perfectly capable sidekick, and Rebecca, voice by Sally Struthers, is a smart, eagle-eyed, tough businesswoman and loving mother. (I love how all three of the main characters often get themselves into trouble.) Her daughter, Molly, may annoy some people but I was okay with her; it helps that she isn’t in too many episodes. The few times she and Wildcat get together are wonderfully sweet, especially since Wildcat has a savant mechanical mind but simple pleasures. His affection for kids and innocent animals is contagious. Then there’s Shere Khan, the imposing, ruthless businessman that quietly rules over the show, and it’s always a treat to see whether he’s being villainous or righteous, or some grey area in between. We have Louie, the bar-owner, playful monkey that often tags along with Baloo on the more epic adventures, and there’s Colonel Spigot and Sergeant Dunder – the former being a sad, less-then-threatening leader of the Thembrian Air Force, the latter being a scapegoat to Spigot’s threats but being a close and secret friend to Baloo.

It’s a great, varied cast, especially if you add to it the wonderful, wacky one-off characters that pop in now and again. The late Phil Hartman voiced a smart aleck pilot named Ace London in “Mach One for the Gipper,” bringing an exciting character dynamic to a typical “switched packages” plotline. I’m personally a huge fan of Doug Benson, a terribly over-zealous little gimp who tries to invade Louie’s bar with Shere Khan’s men. (If Mad Men creator Matthew Weiner admitted on his death bed he based Pete Campbell on some character from “some Disney show,” I’d jump up and scream, “It’s Doug Benson from TaleSpin, and also, I fucking knew it!” But I digress.) These various one-off characters really come in and shake things up, adding the kind of dynamics that give Talespin the pulpy, fun edge it deserves.

TaleSpin isn’t perfect, for sure. “Destiny Rides Again” is a rare total misfire, with bad animation and a severe lack of focus, and the villain is just not compelling at all. Two episodes, “Last Horizons” and “Flying Dupes,” while narratively fine, delve too uncomfortably into ideas of overt warfare and terrorism – which subsequently led to their banning. And physics? Please. In “All’s Whale that Ends Whale,” Baloo manages to carry a giant blue whale on the top of the Sea Duck, which is just mind-blowingly, hilariously outlandish. Then again, TaleSpin earns it, since it’s so entrenched in its pulpy origins, its cartoony sensibilities, its fantastic wold-building, and its distinct, grounded characters. In that respect, TaleSpin truly was one of a kind.

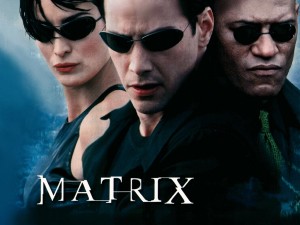

What is The Matrix? The Beginning of the Bloated Franchise

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Film, Television, Uncategorized, Webtoon, Writing on September 11, 2013

The casting of Ben Affleck as Batman in the soon-to-be-teased-relentlessly Batman/Superman film caused quite the stir among the internet, filled with spiteful Twitter comments, rage-filled Facebook posts, and lists-among-lists of why he’d be both great and terrible. Of course, this kind of massive knee-jerk response is nothing new, since there was a tremendous amount of it when Heath Leather was cast as The Joker, or when Michael Bay announced his take on the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Riling up the fanbase has become in itself a new form of marketing, whether in positive forms (which is the key to Comic-Con’s specifically-designed trailers and teasers and… amusement rides), or negatively, which one could say is what propelled a giant portion of controversy over Man of Steel and World War Z. There’s no such thing as bad publicity, and to studios, all they really care about is that sweet, sweet green.

I wanted to take a step back, though, and look at where we are now. Watching this geek-based reaction from a distance, it’s rather crazy if you think about it. This kind of response would have been completely unheard of back in the 90s – hell, even in early 2000s, this egregious “stirring of the pot” would have been nigh impossible to do. Tracking this kind of response backward yields some interesting results – through Batman Begins, Iron Man, the entire Marvel film universe, Scott Pilgrim, Indiana Jones and the Crystal Skull, Harry Potter and Twilight, just to name a few. Sure, the emphasis of “the franchise” has become the raison d’etat of Hollywood nowadays, especially since overseas is now where the real money is (resulting in sequels to films that hardly deserved them – there’s a third Chronicles of Riddick, despite the second one completely bombing). The question is, where did this out-of-control bloated behemoth stem from? Oddly enough, it all began with one film that indeed tried to spread across all these entertainment platforms, and failed. In its ashes was born this blockbuster monster of cinematic proportion that is now creeping into television, video games, comic books, and animation. Enter The Matrix.

——————–

It seems so far ago, but when The Matrix was released way back in 1999, it was essentially The Pirates of the Caribbean of its time: a pleasant surprise that no one was expecting. Sci-fi films were still relatively niche and most of them that were released in the late 90s were terrible, just like any other pirate film that entered the cinematic landscape. But here was The Matrix, its tinted green cinematography overlaying audaciously new (at least in America), gravity-defying fight choreography, all couched in the basic question of what is reality, which seemed particularly relevant in the rise of what the internet and virtual reality were soon to become. The Matrix was an eye-opener, and while I personally was somewhat lukewarm to it when I first saw it (I warmed up to it more on subsequent viewings, but I’m still not what you would call a fan), I can’t help but acknowledge the power it held, especially within the geek community, which at the time still was a forgettable market to Hollywood. Fansites exploded across the internet, and people, for a long, long time, cosplayed in their black trenchcoats and sunglasses as they went to see the film over and over.

No one knew it at the time, but this was the beginning.

The Matrix nabbed over $450 million by the time the film ended its theatrical run. That cashflow began all the talk and speculations of a sequel, which is normal for any winning film, but the Wachowski’s want to do something insane – make TWO sequels. The “trilogy” concept more or less died out with Indiana Jones, and the only thing that was considered worthy of it was the Star Wars prequels, and we all know how well that turned out. The same sentiment, of course, could be said of Reloaded and Revolutions, and both franchises showcased how the money-making bloat of the summer film franchise could overcome both critical AND public conception. But unlike Star Wars, which was always (and will always be) an unstoppable franchise force, The Matrix was new, and while the first film was proven hit, the question of whether it was franchise worthy was something else entirely.

The Wachowskis, of course, sold us all a bill of goods. And it’s not as if The Matrix didn’t have enough content to sustain a number of new, interesting, and intriguing stories within its premise. With all their claims of possessing numerous stories to tell, it’s extremely surprising that Reloaded and Revolutions were what we got. In addition to all that, though, were ideas that slipped its way into different media – anime (The Animatrix), video games (Enter The Matrix, The Matrix Online, and The Matrix: The Path of Neo), and comics (The Matrix Comics). The Matrix franchise was trying its damnedest to worm its way into the pop culture conscious just like Star Wars did so many years ago. But there was a glaring problem: the sequels kinda sucked, about half of The Animatrix animes were in any way decent, the games were broken and not very good, and comic culture wasn’t prevalent enough to warrant enough a large readership for the comics themselves.

The problems with Reloaded and Revolutions were twofold, narratively and thematically – they took focus away from the cool (and much more interesting) parts, the Matrix itself, and focused on Zion, the “real world,” which the writers failed to mine for anything worthwhile. Secondly, they turned the philosophical questions of reality and instead asked religious ones, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing per se, but again, the Wachowski brothers weren’t half-assed to be nuanced, and when they were, it was nonsensical. The games, the comics, and anime were supposed to answer all the lingering questions – but 1) the internet had yet to become so interconnected to the various media forms, so many people barely bothered with that, 2) the films themselves were so problematic that few people actually cared, and 3) those that did were only left with MORE questions. (In some ways, this is what doomed Tron: Legacy – there’s little interest in exploring a franchise if the original source isn’t all that good in the first place.)

But let’s be clear here: the failure of the games and mediocre reactions to The Animatrix would have signaled that this crossing-of-the-media-streams was fatal. Sure, it made money – a lot of money – but it was so complicated and convoluted that by the end of it all, Hollywood rightly thought it wasn’t worth it. It was most likely Harry Potter or Lord of The Rings, the successful book series turned film in 2001 that really turned all that around. Looking at the remnants of The Matrix, everyone learned some valuable lessons – primarily to work with franchises that were already established and easier to comprehend. Coupled with the rise of Comic-Con and geek culture (along with social media), Hollywood specifically realized that utilizing these established fanbases and liberally sprinkling them with controversial BS would be all that was needed to make this bloated, endless machine of summer franchises, arguably made purposely controversial to increase buzz. There’s no way that the Ninja Turtles film will be any good, but every site seems rabidly fascinated with each and every casting call.

From the ashes of The Matrix franchise, came forth the endless stream of loud, riotous, special-effect heavy franchises that rip through theaters and tear-ass across theaters, TV, comics, and video games. Hollywood learned lessons from those burning embers, lessons that now have been taken too far in the wrong direction. Perhaps we need a similar crash-and-burn these days, but I doubt it will be enough to stave off the bloated behemoths coming to theaters in the years to come, and certainly won’t end studio executives mining the dregs of our entertainment past to find the next new endless franchise – I’m pretty sure there will be a Matrix reboot or TV show in the next five years. Yet for a moment, The Matrix was a thing, and we experienced all of it, unwittingly opening a door that we may never close.