Archive for category Television

Star Vs. The Forces of Weirdness

Posted by Admin in Animation, Television, Uncategorized, Writing on July 6, 2017

There’s an episode in the second season of Star Vs. The Forces of Evil called “Trickstar.” Weird Al Yankovic voices a creepy magician named Preston Change-O, who is invited to the birthday party of Marco’s sensei (at this point in the series, Marco and his sensei are friends for some reason. I’ll get into this in a bit.) Star, she of the magical propensity from the alternate world of Mewni, vaguely recognizes Preston and begins to suspect that something is off about him. Indeed, when Preston performs a magic trick, and his audience cheers, Preston sucks up the energy from their enthusiasm. He literally sucks in their “joy,” and his hat grows longer. It’s kind of a ridiculous visual. Anyway, Star recognizes this danger and tries to warn everyone, but those around her deem her a spoilsport – someone who’s trying to steal all the attention from the sensei’s festivities. Ironically, the episode does purport that Preston’s joy-stealing is, at worst, just a small annoyance: no one is deeply affected when their joy is snatched, and Star’s obsession does make her seem overzealous (the episode never quite expounds on what exactly this “joy” is, undercutting the plot; I’ll get into that deconstruction later). Well, no one is affected but Jeremy, whose joy seems like it’s completely gone, and is left sitting on the sidewalk as an ultra-depressed husk. The show posits Jeremy as kind of a joyless loser, but not the kind whose captured happiness seems warranted. Jeremy is all but rendered useless, but other than that “Trickstar” tries to be clever and undercut a common animation plot trope (with… another plot trope?). It doesn’t quite work.

Star Vs. The Forces of Evil has had a hell of a second season. The first one was a fun, wacky romp of adventures and insanity, with a John K. sensibility that overcame the weaknesses of some of the characterizations (most notably in Marco’s friends, who are rarely seen in the second season). The show’s sophomore run toned down the abject silliness a lot, opting for something a vibe that is split between Steven Universe and Adventure Time; the aesthetics are more grounded, measured, and methodical. It’s a pretty notable shift, and it’s a shift that’s not just regulated to the animation. The characters are more… well, I don’t want to say mature, but they are more distinct, more complex in a way that suggests the writers are pursuing long term development for its cast. What makes that stand out, however, is in order to do that, Star Vs. has decided to travel down some insanely odd, unusual, unconventional narrative paths to get there.

I think about that “Trickstar” episode a lot; it’s such a good example of what the show seems to be trying to do, and yet, stumbles on at times. I think the idea of subverting the narrative trope of a figure who sucks some kind of “essence” from people is worthy of doing, but I question the end result when, essentially, one character is effectively destroyed by it, and the weird, tonally off, ambivalent/ambiguous/indifferent theme of the entire episode (let’s be clear: Preston is stealing something from people, and whether or not it’s “harmless” is besides the point – it never was his to take). Star Vs. is clearly eager to subvert and/or deconstruct the kinds of episodes we have come to expect in our animated series. I don’t think it does a great job; or, more accurately, I don’t think it has quite a handle on the full extent on the narratives it tries to subvert or deconstruct (certainly not to the extent that Gumball does, which understand its tropes in minute detail so that its subversions/deconstructions work beautifully).

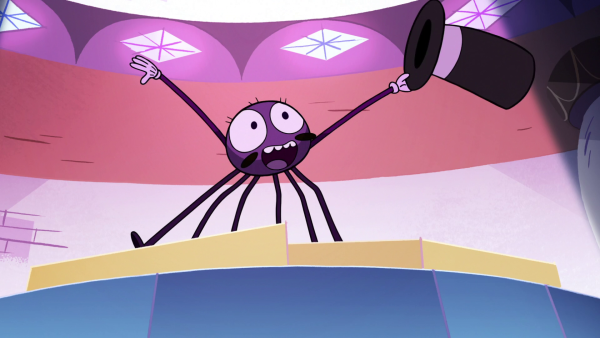

Take “Spider with a Top Hat,” a wildly off-beat episode in which we explore the lives of the very strange, whimsical animals that zap forth from Star’s wand. The creatures spend their lives within Star’s wand like a TARDIS, prepping their existence in order to do battle when summoned; a hapless, cheerful spider at the center plays the role of moral support for these magical warriors. The spider is also pining for his chance to be summoned into battle as well, even though he can barely break a wall with his head. This…. all works better in context, its baffling premise making more sense on the animated screen. It’s a narrative that’s certainly unexpected, but waddles into laziness when the spider, upon being summoned in desperation during a viciously tense battle, suddenly deploys a gattling gun from underneath his top hat. It’s a sudden, throwaway climax to a unique story with a unique premise: the kind of answer you’d find in a notebook of a eight grade boy. “He had a BADASS gun inside him all along” is flat storytelling.

That’s the kind of episode development that hints at Star Vs.’s core issue. It’s second season truly seeks to tell very unique, very audacious stories, but in many ways struggle to push that desire into something meaningful or perceptive. All of the crazy, wild narrative beats and questionable characters are put in place to throw audience expectations askew, but it’s clear that’s just all the writers want to do. The main thematic thrust is about insecurity, mainly centered around a jealousy Star develops when Marco and Jackie (a typical bland, “chill” female character) begin a relationship. Insecurity is part of most, if not all, the episodes of the season, and you can make the raw argument that these off-kilter storylines are meant to instill a level of discomfort and awkwardness in the viewers as well – you’re supposed to feel uncomfortable from the “incompleteness” of an episode, to best reflect the uncomfortableness felt buy all the characters, their relationships, and what they’re all going through.

It’s extremely tough for me to buy, though, as some of the decisions feel less like a bid for thematic resonance, or connections towards insecurity and discomfort, and more just narrative curveballs for the sake of them – both in characterizations and it storytelling choices. For example, Star Vs. opted to lean on an assortment of new characters defined by a “quirk” that’s less “pixie” and more “disturbing”. The first episode introduces a women who collects hair; when she admits this, there’s a music cue that indicates danger. But she’s anything but: she in fact helps Star through her predicament. Which is fine, within the broad, generic lesson of not judging books by their covers. The overall impact of her appearance is moot, though: other than a reference to this woman and her weird hobby later in the season, she feels like a waste of a unique character. Other weird characters include a dog suffering with depression, a insecure being with talking snakes for arms (who gets in way over his head), and a former Mewni warrior turned homeless-sociopath on Earth. Each character is unmistakably distinct, but they never leave a lasting impression. What purpose do they serve, particularly in a season clearly working its way towards a bigger, grander arc? Even recurring characters feel formless. I somewhat can abide by Tom and his anger issues, but he functions better as a toxic, masculine obstacle to Star than jerky man-friend to Marco. I can’t say the same for Marco’s sensei, whose friendship makes less sense than Marco’s original first season friends – at least they were in the same grade as him. Marco’s sensei is a pathetic manbaby who more or less guilts Marco into befriending him, which in and of itself is a pretty toxic event.

And sometimes, I think the show misunderstands the difference between insecurity and personal secrets. “Naysayer” involves a curse that’s supposed to get Marco to admit his deepest secrets, but the episode ties them to his insecurity, and fails to realize they’re completely different. Nervousness in asking a girl out – and the hundreds of reasons that one conjures up that would prevent said girl from returning the affection – is the key to Marco’s insecurity. “Naysayer” forces Marco to just say a bunch of weird personal stuff that he does. I get that the show is trying to tie those personal behaviors to his fear of asking Jackie out, but since we’re not clear on what specifically about himself and those behaviors that worries him in relation to Jackie, it comes off completely the opposite of what the scene probably intended. (You try telling someone you barely know all the weird shit that you do out of the blue.) But since Jackie is barely a character, she’s totally cool with it all.

This is, in some ways, a manifestation of an issue that bogged down the first season: Marco receives quite a bit of screen time for a show ostensibly titled Star Vs. the Forces of Evil. And it’s not as if Marco is a bad character. He’s clearly an important one as well. But Star’s conflict, whose personal sensibilities and attitudes butt up against Mewni’s expectations and historical legacies, is a juicier, meatier narrative than anything to do with Marco. While I admire the second season’s attempt to blend her conflict with the emotional struggle Star is going through upon learning of Marco and Jackie’s romance, it still remains at odds. It feels like a narrative step back from the lesson she learned in “Sleepover,” where crushes and desires ebb and flow overtime, but it also feels like a secondary conflict forced to the surface over the more intriguing narrative of the bizarre Mewni situation involved Ludo, Bullfrog, the return of Toffee, Glosseryk, and Star’s own mother. Also, to be blunt, the narrative building of this conflict comes off incomplete, a smorgasbord of mediocre, world-building, wheel-spinning that, to me, signifies a backstory that’s still being worked on. Nothing that occurred this season seems meaningful, important, or intriguing enough to follow. The reveal in first season’s “Mewnipendence Day” – that Mewni was most likely the aggressive force that subsumed the more innocent, native monsters – feels more worthwhile than the vague information that dripped out during the course of the season.

Looking back over that second season, eyeing episode descriptions while re-watching select ones, I admit that despite my criticisms, my curiosity is still piqued. Yet it’s not for a real desire to learn the secrets and truths of the world and history of this Mewni/Earth setting (and the characters that inhabit it), but more for the sake of relief – an assurance that the creative team does, in fact, have a real long-term arc ahead of them. I’ll swallow up Star’s personal feelings and heartache if that struggle is dealt with in strong collaboration with the greater conflicts and reveals that will emerge from what Ludo, Toffee, Glosseryk, and the entire Butterfly family holds. What do we know at this point, in terms of the overall story? We learn that Star is extremely powerful, which would have been better served to learn as we see Star’s power grow (we don’t really see this). We learn someone is “draining all the magic” in “Page Turner,” which is just a nebulous statement – why should be concerned about this? And by the season finale, we learn that Toffee is back, which is cool (Toffee was one of season one’s greatest characters), but we don’t know what this means.

And yet, I don’t think that the second season of Star Vs. is bad, per se. A lot of it is great, and interesting, and just weird enough to keep paying attention to, and it’s worth at the very least talking about, way more than any potential Marco/Star ships. I do think that, in its desire to be part of the pantheon of great cartoons like Gravity Falls, Gumball, Adventure Time, and Steven Universe, it sought depth and irony and deconstruction and subversions, but it all amounts to blank slates and purposely confusing oddities; its weirdness is the animated version of what Matthew Christman describes as (animated) TV becoming respectable without getting better. For all it’s faults, I do respect the hell out of Star Vs. The Forces of Evil, and maybe its third season premiere will tie this all together in some significant way. But it’s desire to be a game-changer makes the entire season seem like work: I can feel the effort and strain behind it to be “talked about.” What I don’t feel is the one thing that Star herself would want to be: fun.

Why Bunnicula Is One of 2016’s Best Animated Debuts

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Television, Uncategorized, Writing on April 12, 2017

In 2016, Cartoon Network attempted to rebrand Boomerang, its sister channel that airs an assortment of classic cartoons and nostalgic ’90s productions. Along with the newly-fashioned logo, Boomerang broadcasted three new shows: Be Cool, Scooby-Doo, Wabbit, and Bunnicula. Be Cool, Scooby-Doo, which I reviewed here, was clearly meant to be the flagship show to capture new viewers for the “new” channel. Scooby-Doo fans are a quiet but dedicated bunch, and their eyeballs would help steer the channel in positive direction. Wabbit, the newest iteration of the Looney Tunes franchise, was essentially the version of what The Looney Tunes Show was originally meant to be. Its use of classic characters and short-length format would fit perfectly between old and new shows, and meant to appeal to those (dwindling) fans as well. Then there was Bunnicula – a curious show based on the classic book series of the same name. There wasn’t much of a big push for this show, certainly not in a way that would scream “check out the new Boomerang!” It’s hard to say what role Bunnicula was supposed to be in the overall rebrand, but it’s clear it wasn’t supported but CN bigwigs.

The rebrand was, for all intents and purposes, a failure. Be Cool, Scooby-Doo brought in its fans but they weren’t sitting around for the overall Boomerang change-over. Wabbit struggled to grasp the kind of manic energy that the best Looney Tunes works could muster; its skinny designs and muted color palette didn’t help much either. And, again, there was Bunnicula. The off-kilter cartoon by Jessica Borutski and Maxwell Atoms had a less-than-average pilot and made an strange choice in casting Sean Austin to voice Chester and Chris Kattan to voice Bunnicula – the latter of whom barely speaks any actual words. Using non-typical voice actors to voice cartoon characters is a fairly dangerous move, and that pilot suggested some basic, cartoonish antics – Tom & Jerry-level slapstick within a soft-horror atmosphere. Nothing suggested it was worth watching, in other words. But it’s now clear that this was all set-up. Bunnicula quietly uses its pilot and subsequent episodes to build a genuinely creepy and funny show that manages to depict three specifically-cliched characters with layers of complexity that become more and more noticeable over the series’ run.

[As part of a sudden new approach to Boomerang, a number of episodes have been placed on its online streaming site, which requires a paid subscription. Time will tell if this will be more effective than their cable rebrand attempt.]

It’s common for characters in cartoons to exhibit various stock traits that are utilized to incite conflicts that lead to comedic set pieces or low-key dramatic beats. The story usually take precedent, in which characters’ personalities and behaviors butt up against other characters’ personalities and behaviors, or some broadly ludicrous situation. The sillier the cartoon, the more exaggerated those traits will be. Traits may be slightly adjusted as episodes go along, but there’s rarely much examination on why certain characters are the way they are. The nerd kid is the nerd kid. The spunky gal will always be the spunky gal. The stupid goofball is, unfortunately, the stupid goofball, day in and day out. Bunnicula is different. It definitely exhibits the exaggerated energy of a silly cartoon, but it puts more careful consideration into its characters (particularly Chester and Bunnicula, but Harold as well) than you might expect. Bunnicula, on the surface, is about a scaredy-cat, a dumb dog, and a carefree demon bunny getting involved with wacky situations. Bubbling underneath is the story of a family of pets with strong, personal, problematic traits that they gradually work through so as to try and be there for not only each other, but for their owner as well.

Bunnicula is a far cry from its original source. They’re not old-hat pets owned by a boy and his family, but semi-new pets procured by a young, tomboy-ish girl named Mina and her father. Chester, Harold, and Bunnicula know each other of sorts, but it feels like they’re still getting the hang of being around each other, and around Mina. They clearly love her, but they’re working through the particulars of what that entails, particularly Bunnicula. They’re also working through how they exactly feel about each other, as their comic traits are used to mask or distract from their truer feelings for each other. All of this takes place within a New Orleans locale (an inspired setting to be sure), filled with various kid-friendly (but still creepy) horrors and monsters. Yet in the midst of all that, these three pets seem to grow… well, if not more fond of each other, at least more understanding of each other and themselves. They incrementally discover that their base traits are something that they need to work on and work through – not just specific traits for the comedic sake of it. (Even in the chaos of the pilot, “Mumkey Business,” it’s clear that Bunnicula expresses a slight change of heart towards Mina, upon realizing his causal associations with dangerous creatures could harm her.)

Bunnicula, at the base level, thrives on an old-school cartoon charm and sensibility. Molded off the basic premises of Hanna-Barbara cartoons (particularly Tom & Jerry), Bunnicula visually and narratively exhibits an artistic design that would be at home in the ’40s and ’50s. Harold is a clear homage to Scooby-Doo himself. The characters’ hands can transform from animal paws to actual gripping fingers in an instant. Characters pull items out of nowhere from behind their backs and possess pockets in their fur whenever they need them. Physical, violent humor is the norm, if not as extreme as those classic shorts were. It’s righteously self-aware. Chester, Harold, and Bunnicula function on a single trait that instigates, or mitigates, the plot. It does Wabbit better than Wabbit does Wabbit.

Yet unlike most classic shorts, its three leads are driven, at a base level, by genuine love. It’s probably the first cartoon of its type where characters actually say the words “I love you” to each other, even if after the stress of a crazy story. It’s a show where its cast deeply care about each other, even if they have to be reminded of it. Their endgame protection of Mina from the disturbing creatures around them keeps them successfully grounded, even when their intrinsic traits push them to their extremes. Bunnicula himself is wildly amused by these horrible creatures, but needs to reminded of their danger to Mina (and by proxy, Chester and Harold). Eventually, he calms down. Harold is less complex – a simple dog who often gets the buffoonish jokes, but he also is more emotionally open and honest. He’s the first one to express love for others and to whom Bunnicula and Chester most likely express their affections. (This is most notable in the episode entitled “Bearshee,” where Harold plays diplomat between the easily scared cat and a confused, frightened ursine specter.)

Then there’s Chester.

Using Sean Austin as the voice for Chester in retrospect was a good idea. Austin captures that over-the-top energy that’s often required from the character, but he also manages to nail a sad vulnerability in the character that becomes clearer in each episode. Chester’s fears are both exaggerated and sensible, but also weirdly indicative of something, perhaps, darker and lonely. (Nothing exemplifies this more than his final speech in “Chester’s Shop of Horrors.”) He often desires to be a human (“Curse of the Weredude,” “Nevermoar”), for example, and it’s tricky to tell if it’s just to escape being a cat, escape being afraid all the time, or to be respected for his “true” self. (Arguably, it’s all three.) He desires the simple, finer things: a good crossword puzzle, beat poetry, riddles, sci-fi. He’s also kind of a control freak, but it’s not driven by an inflated sense of self-worth – not entirely. It’s really to have some sense of control over his own life, in a world of random terrors and horrors that come to afflict him and his world (darkly captured at the end of “Puzzle Madness”). At times he will go overboard, torturing Bunnicula or deeply believing he deserves good luck at the expense of others’ bad luck. Chester’s fears and insecurities aren’t wrong, His reactions to them often are, but also, he can’t help it.

Chester, Bunnicula, and Harold are who they are, and Bunnicula takes care (for the most part) to make sure their actions and attitudes make sense, that even when they butt up against each other, that it’s all part of a “larger” struggle to find common cause or affection among each other. Bunnicula shows that that kind of emotional camaraderie is a hard thing to do. There’s no grand epiphany – partly because if there was, there’d be no show. But there is a gradual, tedious, comical struggle for the characters to accept each other, and their flaws, and their insanely divergent personalities. Bunnicula is about how love trumps all, even within the context of a wacky cartoon, but it also shows how tricky it is to let that love win out, especially towards those who represent things you don’t even stand for. There’s real affection between the characters, but it’s hard for them to see it, and the show somehow makes it fun to see them try.

Tip from Home: Adventures with Tip and Oh is the Young Black Female Lead We Need Right Now

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Television, Uncategorized, Writing on August 24, 2016

Home: Adventures with Tip and Oh is based on the Dreamworks film Home, a buggered, incomplete piece of animation that never quite grasped the satirical edge needed to portray the abject and complete removal of citizens into makeshift suburban prisons. Home cared little about the uncomfortable connotation of such a premise, which resulted in a plot – in which a young black girl teams up with an alien outcast to try and find her mother – that could not shake off its racially-coded baggage. I know. I know. I wish I could just ignore the analogies – the wholesale removal of people from their homes, the wholesale removal of African people from their continent, the constant splintering of slave parents from their children to foster an economic system that possesses ramifications that last even till this day. But what you need to understand is that it is so, so hard, and Home did little to ease that discomfort from my mind.

In that regard, I had very few expectations of this show.

If a Home TV series had to be made, the best bet would be to ignore that entire premise and forge onward with new, unrelated storylines. Adventures of Tip and Oh does for the most part, although the occasional exploration of the Bov’s cinematic past actions is as awkward as you’d expect (more on that later). The animation is decent; the character designs are off-putting, as typical of Thurop Van Orman’s style, but functions well enough in movement, and viewers will find themselves getting used to it fairly quickly. The character choices are fairly trope-y and questionable, with Donny being a Mr. Krabs-esque non-entity, Sherzod gearing up to be the most decisive character in a while, and Lucy exhibiting a certain level of air-headedness that doesn’t seem to fit a single mother living in Chicago. These, and other creative decisions, suggest the writers are still working through some issues, but there is one thing that Netflix’s new show has right: Tip herself.

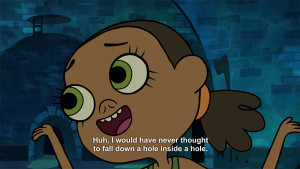

I didn’t warm up to Gratuity “Tip” Tucci at first. She seemed a bit all over the place. She is inconsistent, a bit aggressive, a bit loud, a bit too weird – especially compared to her cinematic counterpart. But then I realized something: that is the point. Tip is purposely, uniquely, her own girl. She is an eighth-grader who possesses her own very limited, very vain, very specific point of view. Her aggressiveness, loudness, and weirdness is uniquely her own. The writing doesn’t quite do her any favors, specifically in terms of the situations that she finds herself (and Oh) in. But Tip herself is special. She is unabashedly herself, not particularly concerned to fit within the parameters of young girl character templates – specifically, young black girl characters – that came before her. She is Penny Pride – clever, determined, confident to a fault – mixed with Star Butterfly – extroverted, adventurous, out-of-her-league. Tip is confused, lost, conceited, goofy, and, yes, even grating. She is all those things – which makes her the best, most important young black female lead for children today.

I need to reiterate something: other than Doc McStuffins – a show for preschoolers – we do not have a single animated show on the air with a black girl as a lead. Mostly cartoons are driven by young boys (or talking animals). There are more shows now with girls as leads, and/or shows with strong feminine characters. But they’re mostly all white (save for Steven Universe’s Garnet, which is another matter entirely). And that is fine. But in this era and in the call for more diversity, it’s telling that, as usual, young black girls are continually, routinely ignored. (Full disclosure: I pitched this piece to a well-known site, which was rejected, and which I deeply believe contributes to this problem.) Seeing and experiencing someone like Tip on my screen felt revelatory. It made me realize how limited in scope my expectations of what young black girls could be. (Note I didn’t say “what black girls should be,” which is an extremely important distinction.) I love Tip because, sometimes, I don’t love Tip. I love that she’s sweet and loving and naive and annoying and too much and quirky and super-weird and sometimes “uppity.” Black girls need to see this. We all need to see this.

This scene epitomizes the kind of person Tip is as a character. There’s no contextual reason why she sniffs herself (they’re in a sewer, but there’s no reason why she sniffs her armpit versus any other part of her body), but it shows her her spirit, vanity, and goofiness all in one brief monologue.

Tip isn’t African-American. She’s Caribbean-American. Her grandparents immigrated from Barbados; Tip is second-generation. The show doesn’t play around too much with this, although it is nice to see when they do. (I would love to see more Barbados-inspired bits on occasion, in the fun ways that Sanjay & Craig sometimes played with its Indian-related bits.) I don’t expect the show to really do that, though, mainly because the writers don’t seem to really grasp the full relevancy of what they have in a character like Tip. There’s theoretically a lot to unpack in a show in which the Bov implemented forced displacement and occupancy, where the setting is Chicago, and where Tip and Lucy live by themselves sans a father figure. When Tip’s grandparents visit in “Wrinkly Humans People,” that awkwardness is palpable, but the writers don’t see it. After all, her grandparents deeply distrust the Bov for what they did, and you honestly can’t blame them. Yet the show works it so as to suggest that it’s her grandparents that are in the wrong, that they’re the ones who are, essentially, the bigots, since they just can’t get over what the Bov did. Well, of course they can’t. History is ugly.

Even still, there is potential here. There is a rich complexity in the idea of Tip’s broader acceptance of the Bov and, specifically, Oh, and how that comes up against the reality of what the Bov did. There is perhaps something to how easily a young Tip has forgiven the Bov in order to maintain the stability of her small family unit, and how that continues to push up against those still harboring resentment towards their occupiers-turned-neighbors. It would be deeply interesting to see episodes in which Tip has to, in some way, address how she justifies her love for Oh, as opposed to her past hatred for the Bov’s role in separating her from her mother. Adventures with Tip and Oh might have been better served ignoring all that overall, but although I do applaud the show for dipping its toe into the thornier sides of the film, I doubt the writers have the temperament to hit such dramatic notes.

That’s a dramatic layer way out of reach for this crew. At this point, in its first season, it would be just enough to take a fun, deep look at Tip herself (in the context of a young black eighth-grader with only a mother living in Chicago). As a unique character, the writers provide her with the variety of traits that I’ve mentioned earlier. As a character who will be developed, that where the writers fall short. It’s tricky, because the show doesn’t need to be an in-depth (if silly) examination on what it means to be a young black girl in Chicago – aliens or not. But it would be worth exploring some of the issues unique to that worldview and experience. The clearest example of this dilemma lies in “Angerdome,” an episode in which Tip deals with her anger. There are volumes of content that could be written that explores the social exploitation and discrimination that exists within the “angry black woman” trope. It is both vicious (which posits all black women as unstable and prone to violence) and commodified (from the lighter-but-overused “sassy” trope, to pushing their angry reactions on reality TV). It’s hard to say how the writers see all of this in “Angerdome,” though. There’s a moment, after various characters tell Tip to calm down, where she proclaims, “I’m allowed to be angry!” and it is wonderful; filled with the personal, determined, defiant spirit that young black girls need to hear. Yet the power of that statement is undercut when, immediately after, Tip resigns to needing help (and an outlet) to deal with her anger.

That’s what makes it hard. There is the real, distinctive lesson which allows kids to understand that having an outlet to deal with anger is important, and I can’t fault the show for dealing with that (although the answer they come up with is muddled). At the same time, the show mostly ignored the opportunity to explore Tip’s individual struggle with what it means to be a black girl who gets, and is allowed to be, angry. It’s a powerful statement that the writers fail to notice as a powerful statement. It’s part of the overall verve of the show, really. It’s great to see Adventures with Tip and Oh use a character like Tip to have fun with the general complexities of childhood, especially within such a specific premise. It’s tougher to see this done separate from the unique characteristics and history that Tip (and the show) embodies: the black, only-child, fatherless, Chicagoan setting. The universal ideas are fun, and pushing them through Tip is wonderful, but the writers have an opportunity to really explore Tip’s experiences at a personal, raw level, and I don’t think the writers see it – or they refuse to.

Still, I praise the fact that a character like Tip exists. She is simultaneously fun and frustrating, and it makes her necessary to see a character like her on television. What ever issues or concerns that may happen around the lives of the Tuccis (which, for all we know, could be fixed by season two), Tip’s goofy, abject, unforgiving weirdness and quirkiness – so often contributed to white women to the point of a dated, oft-misunderstood trope – has been finally applied to a young black girl. It’s just good, refreshing even, to see a black girl outside of a typical “no-nonsense” role. (Tip is no-nonsense, but it’s defined within her weirdness, not as a sole contrast to those “silly” white kids.) A lot of her appeal is due to the voice artist, Rachel Crow, a 2011 X-Factor contender taking the role from Rihanna from the movie. Rihanna had gumption, but at best her voice work was merely passable. Crow brings a serious, specific attitude to Tip – a rough energy that’s wonderfully infectious (in the same multi-layered cadences that the late Christine Cavanaugh gave to Gosalyn Mallard). She also has a distinct singing voice that manages to add flavor to both the show and the character, without it being too distracting or random.

So flaws and all, I look forward to see where Home: Adventures with Tip and Oh takes Oh and Tip in future stories. The creative critic in me wants to see the show lean a little harder on its premise, on its boundaries and issues, just to see them contextualize how Tip might respond to those tougher dilemmas and grow as a person. I would love to see those issues hit upon, to expose it to kids, particularly young black girls, who struggle through those issues every day. As for now though, I just want to see more Tip. I want to see more of her odd, assertive, annoying behavior. I want to be challenged, bothered, and amused by Tip’s antics, because I want young black girls – and all viewers, really – to understand that being like Tip is okay.

(Final note: I know this is “just a cartoon.” I know I should just enjoy it for what it is. What I’m telling you is, I just can’t. Not with what I know and experienced, not with what I’ve read, not with the history and context of this country and even Chicago itself inside my head, not with the news stories and the personal accounts of people’s experiences shared every single day. I physically, emotionally, psychological cannot separate the two. I can only channel it, and I would hope and love to see Home: Adventures with Tip and Oh do this as well.)