Archive for category Writing

Gargoyles “Bushido/Cloud Fathers”

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Childhood Revisited, Television, Uncategorized, Writing on August 11, 2014

Gargoyles seems to be back into the swing of things now with these two episodes. Although, at this point, I’m starting to see why fans tend to be lukewarm towards the World Tour arc. Part of the problem is that, to me, the World Tour was intended as a breather, as an excuse for the writers to take a step back from their massive mythology and world-building, so they can dole out bits and pieces of that mythology and world-building in manageable chunks. When they do that, as in “Cloud Fathers,” the result is amazing, creating a product that is both fun and rich with deep moments. When they don’t, as in “Bushido,” it results in something merely passable at best and throwaway at worst (like “The Sentinel”). The idea of the World Tour is great; whether the writers are up to it is the real question.

Gargoyles 2×40 – Bushido

Vezi mai multe video din animatie

“Bushido” isn’t the strongest episode, but it’s passable enough, part of the Gargoyles run of episodes geared to be more entertaining than involving. The gang arrives in a hidden village in Japan, and they discover that the gargoyle clan here works in harmony with the humans instead of hiding. This surprises the group, but the Japanese people get away with this because they believe in the concept of Bushido. Bushido is one of those broad ideologies, like “Republicanism,” that’s less tied to specific rules and philosophies, and more to an idea that everyone inherently engages in. The wikipedia link breaks it down, but for Gargoyles, it’s used as a broad “honor” crutch, in the same way most Western takes on Asian culture do.

The episode isn’t nearly as lazy as most of those Western takes though, but there is a strangeness to it that makes it difficult to parse out. One of the Japanese gargoyles, Yama, is in league with the sketchy businessman, Taro, who sends a bunch of ninjas out to distract the town during the day so they can remove the stone gargoyles and place them inside a giant city facade so Taro can show them off, ultimately as amusement park oddities for profit, a la Jurassic Park. It’s certainly isn’t the most involved or most complex of plots, but it’s serviceable, with a few question marks up in the air.

Primarily, it’s never clear why exactly Yama is willing to betray both his clan and the humans. I get the sense that Taro was telling him a bunch of lies so Yama could try to convince the other gargoyles that living isolation was not the way, that opening up their species to the world was truly the way of Bushido (Yama seems delighted at the idea that children will be coming to see them, another Taro lie). This brings up an interesting question – how far do you extend an ideal as beautiful and honorable as Bushido? Is it a concept best kept to a peaceful village, content in their lives, away from fear and marginalization? Or should it be spread among everyone in the world? That is, should those who believe in Bushido deny their self-imposed exile and spread their idea to the world, to anyone who listens?

That, at least, is what I think Yama, and this episode, is aiming for. Once again, the idea of purpose (this time, of Bushido) is the theme here, but the core nature of Yama’s belief is left unclear. I love subtlety as much as anyone else, but that doesn’t equate to ambiguity, so without a scene outlining how Yama and Taro differ, Yama’s realization that he made a mistake comes from nowhere but from the whims of the writer. It’s a disappointing, random moment, but the show plays it well, I think. Yama agrees with Taro, at the very least, to present an idea of showcasing Bushido and their existence to the world. I think he sees this as a positive. But his agreement was based on the idea that, if the gargoyles didn’t agree, they could go home. Taro presents that option at least, even though we know he’d never let any gargoyles out, for his own selfish ends.

The episode doesn’t really get into that though. Yama’s motivation is muddled, and he only seems upset when he realizes Taro isn’t the partner he thought he was. That is, he never sees the concept that “kidnapping gargoyles against their will” is in and of itself wrong, only that it doesn’t work out in his favor. All of that makes his final fight with Yama seems unearned, particularly since he kept insisting that this was his fight alone. Still, “Bushido” is as solid of an episode as can be, with some nifty Elisa moments (I don’t know what’s better, her take down of the world’s shittiest ninjas or directing a car straight into a building), and no one does anything particularly questionable. Of course, all the gargoyles leave the amusement park before the press arrives, making Taro look foolish. Yama apparently goes on a redemption quest afterwards, and I don’t know what happens to Kai, the defacto leader of the Japanese clan. The animation is fairly good, too, so even if the motivation of many of the characters are confusing, the episode commits to its premise, which, by rule of Bushido, is fine by me.

Gargoyles 2×41 – Cloud Fathers

Vezi mai multe video din animatie

With “Cloud Fathers,” however, we’re working with much stronger material, worthy of the Gargoyles mythology and world-building. This episode basically took the mediocre “Heritage” and made it into something substantial, something that involves Elisa’s family and Xanatos, who has been M.I.A. for so long. I’ve had my issues with Xanatos but it is seriously nice to have him back, even if his true endgame is unclear (as always) and even if he’s engaging in cliched villainy (his words!).

Elisa, Goliath, Angela, and Bronx arrive in Flagstaff, Arizona, where they run into Eliza’s father and sister, Peter and Beth. At this point, the Hispanic angle to Eliza’s heritage is all but gone; as it stands, the character is now part Nigerian and part Native American. The episode doesn’t specifically say what tribe Peter is from, but a bit of referential research seems to imply he’s of Hopi decent. And it’s a heritage that Peter wants to have no part of, as at the beginning, we see him leaving his father for New York after a verbal spat.

This starts off like a retread of “Heritage,” but I think this works better because it’s given a personal stake by tying it to Elisa, and by couching it in in Peter-redemption story. It’s not just about a guy who has to connect to his heritage to save the world, part of the not-at-all overdone story threads where the big city ruins people’s closeness to nature and culture. It’s about a person who his embracing his past and culture in order to understand his family and himself. “Heritage” punishes Nick for leaving his home and pursuing Western ideas. “Cloud Fathers” doesn’t judge Peter, but simply tells his story through his return to Arizona and what it means to him.

Xanatos is up to something, which is why Beth called Peter to Arizona in the first place. There’s some craziness happening at one of the mastermind’s construction sites, and a familiar-looking-but-mysterious security guard lets them in. Xanatos arrests them for trespassing, but it was really a means of getting them off the property so they could really investigate the mysterious guard while continuing with their plans interrupted.

After posting bail, Beth and Peter run into Elisa. They exchange information – Eliza fills them in on her travels and the gargoyles (beyond the info that her mother told them), Peter tells her about Xanatos’ actions. The gargoyles go to investigate but they’re captured by the new-and-improved Coyote (4.0). Tied to a sacred sand carving, Xanatos prepares to drop acid on them, hence his “cliched villainy” line. The episode cleverly undercuts this though. Xanatos is using the trapped heroes ploy as an excuse to get the “real” Coyote – the mythical being who has been masquerading as the security guard – out from hiding. Basically, Xanatos was pretending to destroy the carving tribute to him so Coyote would be lured out. It wasn’t working, though, so he has to put in a real death trap to lure him out (if it didn’t work, well… at least the gargoyles would be dead.)

Coyote is a bit of a cipher. All of Oberon’s children are, but even here, Coyote’s actions and purpose is unclear. Coyote, traditionally, is a trickster, but he’s manipulating people here to get people involved to save his carving, particularly Peter (Coyote even takes on a younger-Peter form). Trickery is one thing, since its usually self-serving, but here Coyote is being helpful, changing the odds in the Xanatos/gargoyles fight in the heroes’ favor – which is a thing he can do, as well. Coyote’s abilities to change the game in vague but distinct ways is a bit frustrating, but to its credit, the episode makes it work very well, particularly in getting the stubborn Peter to embrace the weirdness of it all and embrace his past.

It’s also a bit frustrating to see Peter deny everything that’s happening, even with giant walking winged beasts right next to him, but I think it’s less to do with his cynicism and more with his unwillingness to face his past and his father. The episode, again, cleverly implies one thing, what with Peter’s constant refusals to see his father, only to lead to another at the end, where Peter admits his faults and his lover for him, while over his grave. Michael Horse sells the powerful, vulnerable moment, which gives the episode overall a quiet, understated power.

Xanatos’ ultimate plan is to capture Coyote and “convince” him to give him immortality. I like that Xanatos is still harping on this. It fits his character so well, the confident, cool millionaire villain scared of death, always looking for the edge, what with robots and time travel and magic, and now, control over life. I also like the idea of melting down the Cauldron of Life and using its metal to rebuild Coyote 4.0. It’s a brilliant piece of information, which allows the robot to hold Coyote, but it’s not necessary a “stronger” metal, since Goliath easily can jam a metal girder into him. He’s also taken out completely with some sweet Coyote trickery, although it was so obvious what he was up to that I’m surprised Coyote 4.0 fell for it (although he did let Coyote go, which is also a odd bit of stupidity from a Xanatos creation, which even surprised Xanatos).

The episode ends not only with the aforementioned grave scene, but a bit of more myth building with Coyote mentioning that he and Peter are connected, based on the Coyote Dance that Peter did when he was young. I’m not sure how to take this. Does this mean Peter is part magic? Is that in any way related to Elisa? Why is the connection so strong with Peter, and not any other of the many Coyote Dancers that most likely took up that role? The second season is slowly beginning to end, so I’m hoping the show explores this more closely. If not, then this development comes across as forced and unnecessary. Still, “Cloud Fathers” work so well as a Peter showcase that none of the episode’s flaws can hold it back (not so much for Beth, who unfortunately did nothing but spout exposition).

“Bushido” B/”Cloud Fathers” A-

Gargoyles “The Green/Sentinel”

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Childhood Revisited, Television, Uncategorized, Writing on August 4, 2014

Cary Bates is starting to prove to be the weakest writer on the Gargoyles’ staff. I’m absolutely sure that he means well, and I think that his broader ideas are quite workable, in theory. But looking over the episodes he wrote – “The Silver Falcon,” “Outfoxed,” “Monsters,” “Eye of the Storm,” among others – it’s clear that he struggles with conflicting personalities and delving into characters’ psyches, particularly in tense situations. While everyone else on staff is trying to building up the gargoyles and their world, Bates seems satisfied with writing material bordering on fan-fiction. His strongest material are episodes that involve Thailog, a fan-fiction character if I ever saw one – but he works for the show, particularly as both a foil to Goliath and Xanatos. Beyond that, he pretty much tosses Goliath up against another character, and brute forces a relationship (protagonistic OR antagonistic) that never clicks. “The Green” and “Sentinel” are two perfect examples.

Gargoyles 2×38 – The Green

Vezi mai multe video din animatie

“The Green” is an environmental episode, which always garners a sigh, even from the most staunch environmentalists. That doesn’t necessarily lead to a bad, cloying episode by nature, but, like “Lighthouse in the Sea of Time,” it’s clear that the episode is more concerned about teaching a lesson then it is about letting the lesson engage as a subtext to the overall plot (like the gun safety lesson in “Deadly Force”). It’s also… well, I don’t want to use the word “lazy,” but there’s definitely a sense that the episode believes its engaging in plot aspects that are bigger then they actually are.

Goliath, Angela, Bronx, and Elisa arrive in Guatemala, and find another clan of gargoyles battling some nameless construction crew out there chopping down trees. Interesting that the humans here have guns, after all the work the show (most likely by Disney’s demand) did to utilize laser weapons. It makes sense here though, but unlike other World Tour episodes, we aren’t presented with a “face” of the human crew, something to connect to the other side of this conflict (and there is another side, which I will get to in a moment.) The Brazilian gargoyles make a stand, right up until the point Jackal and Hyena appear.

I was kind of thrown off by this. Honestly, after the sadistic, power-mongering behavior Jackal displayed in “Grief,” seeing the two siblings be buddy-buddy is a bit disorienting. I suppose I can swallow that bitter pill if we assume that Hyena was distinctly aware that it was the immense power of Anubis that caused Jackal to act that way, and thus easily forgave him after turning her into a baby. Still, the fact that there’s NO tension between them is odd. The show is filled with moments that put once-collaborative partners at odds with each other, so to not call some attention to the events from “Grief” is just awkward. (Jackal refers to Egypt in the midst of battle, so it’s not like we can chalk it up to being aired out of order.)

Bates has always struggled with characters in ideological conflicts, so here he sets up a plot line so he can focus on cross-cutting fighting, instead of touching upon the farmer/environmental concerns the episode itself brings up. Basically, the four Guatemalan gargoyles don’t have to worry about turning to stone in the daylight due to a sorcerer who created a sun talisman, which is the power source four pendants worn by the those gargoyles that keeps them de-rocked(TM). Jackal and Hyena, after spying on them, do a bit of magic-internet research and discover that the sun talisman is New York. So Hyena is sent to the big city while Jackal stays behind, at the ready to destroy the stone gargoyles once the talisman is destroyed.

A few things. We learn that Cyberbiotics is paying Jackal and Hyena to take the Guatemalan gargoyles down. You would think that Vogel (on behalf of Renard, who is off ill-health), would be down on the plan instead of mildly reluctant. Also, Cyberbiotics have the NY resources to handle the destruction of the talisman – or at the very least throw some support behind Hyena on her mission. Also, and I guess this is part of Jackal’s impatient character, but wouldn’t it have made more sense to at least wait until you physically witnessed the gargoyles change to stone? And, this is more of a nit-pick, but where are Brooklyn and Hudson? The episode just jumps back and forth between the Jackal fight and the Hyena fight without any attempt to making this work on an aesthetic or character level.

This becomes even stranger when the episode starts to get into Ferngully-esque territory. The episode portrays the loggers as evil henchmen randomly cutting down trees, at least according to the gargoyles. But then they bring up the poorer farmers that are cutting trees down for food (well, for sustenance), which creates a morally grey conflict between the gargoyles and Elisa. The gargoyles believe all the trees should be protected. Elisa believes there should be a bit of leniency for the poorer humans. Absolutely nothing comes of this. The episode brings up a situation necessary for compromise, and throws it out the window for the all the fighting. Granted, the A-Team animation team is in full force here, and it looks amazing (particularly the Hyena fight), but in terms of developing the core story and its subtext, the episode doesn’t even bother. A minor rift occurs between Elisa and Goliath, but it doesn’t lead to anything. For a show that isn’t at all scared to get into the complexity of the issues it brings up, Bates hardly does anything with it.

The episode ends with the gargoyles defeating Jackal and Lexington/Broadway besting Hyena. Broadway’s comment about how maybe they should destroy the sun talisman is just weak tension (and I’m not sure why he’s holding it in his hand in stone form, when the Manhattan gargoyles have a room in the clock tower for important objects). Vogel ends Cyberbotics’ contract with Hyena and Jackal, as well as all the potential work they were doing in Guatemala, which probably will pay off down the line, narrative-wise. And to end the moral issue that exists between the pro-forest gargoyles and the pro-human expansion, two of the Guatemalan gargoyles take a floral section of the rainforest with the World Tour crew, which is a non-ending if I ever seen one. I suppose the assumption is that the section will indeed make it to Avalon while the World Tour crew will keep on touring, but that’s a stretch, and also, it doesn’t at all solve the core issue between humans and gargoyles, or even hint at a solution or compromise. Bates seems so focused on the dual-battles that he forgot that there were personal stakes involved, leaving “The Green” very lacking in color.

Gargoyles 2×39 – Sentinel

Vezi mai multe video din animatie

Then Gargoyles decides to bring in aliens, and I don’t know what to say.

Another Bates episode that borders on fan-fiction, “Sentinel” also forgets that the core characters are actually characters, people who are confused and complicated and hurt. Also this is an amnesia plot, which is the worst of all plots. Granted, there’s a specific reason Elisa has amnesia, beyond a lazy “bumped on the head” catalyst, but the execution, again, is just way off.

The crew finds themselves on Easter Island. With Elisa asleep, the gargoyles explore the strange large-headed stone monuments that dot the area. While they’re gone, a strange creature comes into contact with Elisa, and with a quick edit, we see the poor girl wandering around, with no idea who she is. Luckily she’s picked up by Lydia Duane and Arthur Morwood-Smith, the scientists she and Bluestone were protecting back in “A Lighthouse in the Sea of Time.” Gargoyles loves its callbacks, and it’s a show that usually uses them to advance the overall mythology, but here, we don’t learn about them, nor do they exactly lend any assistance to the overall plot. Bates uses them as a crutch, a “Hey, remember these guys?” moment without giving them any substance.

Then things get really awkward. To me, it’s the most shocking scene in the entire run of Gargoyles‘ so far, because of how tonally off it is. The doctors want to take Elisa off to see specialist, but Goliath can’t let that happen. Which comes off a bit forceful, but it’s an understandable sentiment. When Elisa freaks out, Goliath’s reaction is… non-existent. In fact, it’s aggressive. Extremely aggressive. Elisa is terrified and even tries to shoot her empty-chambered gun at Goliath. But Goliath doesn’t even try to talk to her, or try to understand the situation, or express any type of genuine confusion over why Elisa is acting this way. He growls, “You’re coming with me,” then grunts out “Stop struggling,” with absolutely no gentleness that Elisa instilled in the beast via their time together.

I really, really don’t want to go here. I don’t. But with the burgeoning “romance” that exists between Elisa and Goliath (well, it’s more like a platonic relationship based on true respect and hints of affection), the scene possesses, quite frankly, a rapey-vibe. I know that it’s not intentional. I know that I’m reading too much into it. But the aggression, the dialogue, the warm-lighting and staging of the bedroom – it’s difficult NOT to read it as such. The scientists clearly weren’t a threat to Goliath, so with the gargoyle not even trying to communicate with anyone in the room in any way, I just… I don’t know, man. I wish I could just chalk it up to being a poorly written scene, but the implications here are way too strong.

Overall, the episode is just about Goliath trying get Elisa to remember himself and the gargoyles. Barring that, at the very least she should trust her instincts (which is muddled since her original instincts were to shoot him in the face). Come to find out all of this was started by an alien who landed on Earth years ago. He was friendly with the natives (hence the Easter Island heads) and swore to protect them and all humans, then overtime, sans any contact with his species, got a bit crazy. He assumed the gargoyles were hostile aliens who brainwashed Elisa to trusting them, so he wiped her memory. He captures the gargoyles and almost kills them (via some of the strangest weaponry in sci-fi history), but Elisa “trusts” her instincts and frees the gargoyles before its too late.

Forgetting for a moment that the introduction of aliens pushes Gargoyles into a realm that it really doesn’t need to be in (do you not have enough sci-fi/fantasy ideas to work with already!?), “Sentinel” is filled with questionable dialogue, unwieldy exposition, unnecessary characters, and problematic subtext. It, like “Eye of the Storm,” resolves its conflicts in a perfunctory manner, with little to no care of the core relationships between its main characters, nor the secondary characters it brings in. “Sentinel” tries to be about understanding your purpose in life, even when nature of your purpose is unclear or confusing. If that theme was tied to the broken structure of the episode overall, in that way, it succeeded.

“The Green” B/”Sentinel” C+

CHILDHOOD REVISITED – Quack Pack

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Childhood Revisited, Television, Uncategorized, Writing on July 31, 2014

In an unexpected move, Quack Pack smartly undercuts it’s marketing – that is, Disney’s attempts at courting the youth demo masks the show’s commitment to classic wackiness and absurdity.

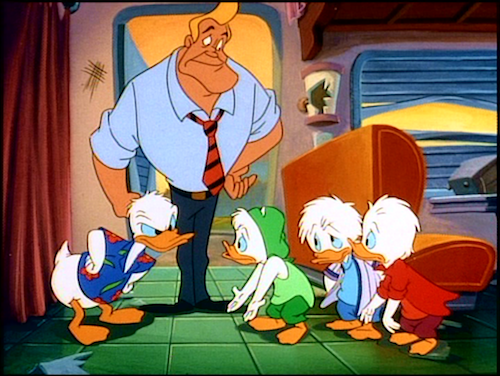

As mentioned in The Mighty Ducks write-up, Disney Animation was really spreading itself thin at this point. Between Gargoyles, Goof Troop, Bonkers, Aladdin, and others, TV animation was going through the last phases of the Golden Age before falling apart. Disney must have seen the writing on the wall, which meant executives doubling down on appealing to the youth demo, which, according to some metrics which will never see the light of day, meant emphasizing young, cool male kids doing cool things like skateboarding, surfing, rollerblading, and anything else that the X-Games and the Winter Olympics made obsolete. So retooling Donald’s nephews, Huey, Dewey, and Louie, as hip, Y-Gen teenagers seemed like Disney’s sad, embarrassing attempt at Poochie-fication. (By the by, I love that Poochie-fication is now a thing.)

Here’s the thing: the problem with Poochie-fication isn’t that characters are just developed solely to appeal to “extreme” young boys. The problem, as Milhouse complained in the infamous Simpsons episode, is that they never get to the fireworks factory. In other words, it’s one thing to make “cool” characters. It’s a whole ‘nother thing to make them so cool as to never put them through the wringer. Youth-oriented characters ought to explode and be crushed, squished, and popped as often as the lame squares that surround them; just because a character is designed to be cool doesn’t mean they’re absolved of flaws and comedic physicality. Poochie would have made a nice addition to Itchy & Scratchy if the sunglasses-and-backwards-cap wearing canine had a rocket shoved up his ass.

So for all the ads and gimmicks of the beanie-wearing fowl triplets of yesteryear rocking out on surfboards, quads, rafting, and skateboards, Quack Pack is not afraid to show that these extreme youngin’s are, well, stupid as shit. A lot of their ideas are portrayed as problematic and terrible, and they have real, unfavorable consequences. Quack Pack shows these youthful spirits engaging in whatever old, white producers deem is “happening,” and I’m sure it made a good reel to satisfy their desire for market branding, but the truth is a lot more intuitive. Quack Pack is more interested in crazy, absurd ridiculousness, setting up such seemingly “radical” moments that lead ultimately to crazy, typical, classic cartoon shenanigans (and in some ways, they herald in the new approach to cartooning).

This is by design. Producers Kevin Hopps and Todd Shelton were more focused on developing the show much more similar to Disney’s classic Donald Duck shorts, and the more you watch it, the more obvious it is that Quack Pack is more interested in Donald Duck than his nephews. It’s through Donald Duck that Quack Pack truly thrives, presenting an opportunity to not only engage in an homage to the classic Donald Duck filmography, but to also create something different, something so absurd and wacky that all that “extreme” content becomes moot. The “cool” stuff is window dressing. The comedic meat of Quack Pack is in how crazy and ridiculous things truly get.

One of my favorite moments in Who Framed Roger Rabbit is the dueling pianos scene between Daffy and Donald. It’s a great showcase for Disney’s and Warner Brothers’ most audacious, craziest, and careless ducks, but as it serves as a good example of Daffy’s daffiness, it also reminds us that Donald Duck is a dick. I don’t mean that in a personal way; this, too, is by design. Donald is a self-centered, greedy (and, by some classic cartoon standards, a misogynistic) jerk, since the comic angle is in watching Donald be a dick, get his comeuppance, get irrationally angry, and get his comeuppance again. It’s formulaic, but animated shorts are defined by formula, and the only thing changes are the various insane circumstances upon which the formula is placed.

Over the years the image of Donald has softened, not necessarily on purpose (Donald’s classic shorts are easily accessible), but mainly due to various, random forces – the lack of popularity of the Carl Banks/Don Rosa comics, Disney’s tight grip of exposing its classics in the pre-Youtube days, the emphasis of Mickey. Donald has become more of a physical comic presence, comically abused in things like Kingdom Hearts, or his few appearances in Ducktales (his softer side also developed since he’s taking care of his nephews), or that one cameo in Bonkers. Yet Quack Pack is attempting to return Donald to his monstrous side, showing him as arrogant, vengeful, psychopath. It’s somewhat of a jarring experience, but it’s arguably truer to the character than we expect.

So when we see Donald go to extremes in “The Really Mighty Ducks,” it takes a moment to accept that yes, Donald has become a supervillain hellbent on attacking his superpowered nephews when they refuse to clean their room. There is no reasoning or “coming to an understanding” between a surrogate father and his progeny – he literally threatens the entire existence of the galaxy to win an idealistic battle over a chore. It’s the nephews that have to quell the fight and learn their lesson. Granted, it’s their fault, but there’s no inherent lesson about responsibility, and Donald certainly isn’t here to impart it. He wants a thing done, and will eradicate all life to see it through, not because he’s an overbearing parent, but because he’s Donald, and he’s crazy.

That’s what gives Quack Pack a surprising edge over its “rastification.” It’s pushes past its image and into absurd, overtly wacky territory, with some of the craziest storylines ever conceived – they’re technically storylines out of superhero and/or serial comics, re-purposed for suburbia. They come across disturbed military reprobates, pathetic alien menaces, typical shady businessmen, and a host of mad scientists, among others, and the cast more or less stumbles into the events, pushing through the insane plot with an almost-reckless abandon. And while all the characters contribute to the events in their own unique ways, it’s Donald who truly has the metaphorical floor.

That’s all not to say the other characters don’t have a role. There’s Daisy Duck primarily, Donald’s girlfriend and a reporter for “What in the World” news. Daisy doesn’t really do much plot-wise (except in “Gator Aid,” a particularly interesting episode where everyone is at their most chaotic, reaching an Arrested Development-like crescendo), but she’s a great character just to watch, going toe-to-toe with Kent Powers (a wildly conceited reporter and ostensibly the show’s antagonist), figuring out mysteries, keeping Donald in (relative) check, and just doing things on her own terms (say what you will about the Disney Afternoon, but they create fantastic female characters). And then there are the triplets.

Huey, Dewey, and Louie are clearly the icons in which Disney hoped to build the show upon. They were given everything a desperate executive would give a “teenager” – sports jerseys, backward caps, dated slang, a “love” for all things cool, extreme, and radical. You can’t deny it, and when you see them run off skateboarding, snowboarding, quading, or surfing, one can’t help but eyeroll. Yet, even through all that crap, the writers do bother to give them individual personalities (even if they’re a bit inconsistent). Huey is the “cool” one, most concerned with image and success; Dewey is the smarter one, who usually comes up with the plans; Louie is the jock and meathead of the group. And for all of their focus-grouped-designed ‘tudes, the show does portray them as characters who fuck up, who (more or less) care about Donald and Daisy, who have their own individual desires, and who, when push comes to shove, work together quite well. Louie in particular became a favorite if only because of how some of his stupid ideas/observations matched many of the meatheads I knew in high school. Dewey instantly regrets his “oh so cool” idea of shoving hot-flavored food into the gas-tank instead of enjoying their high-speed ride. And Huey “oh so slick” dating moves only lands him in trouble when he finds out his crush is planning world domination.

Even despite those ‘tudes, one can’t help but admit that, well, they kinda do act like teenage brothers. Louie loves his comics and obsesses over the “radicalism” of vigilantism (“None Like it Hot,” “Shrunken Heroes”). Dewey is caught up in his emo desire to be alone and obsesses over practical jokes (“Ducklaration of Independence,” “The Boy Who Cried Ghost”). Huey is caught up in his self-image and obsesses over TV personalities (“Heavy Dental,” “Huey Duck, P.I.”) And they all learn that it’s all bullshit in the end, which is good in terms of the characters and its audience growing up. The three shoot the shit and often gets into fights – “Pardon My Molecules” is a particularly good one, where the escalating conflict between Huey and Dewey reaches ridiculous heights, involving cannons and mortars – but when they work together, it works the best, reminding those of us who knew them when they wore beanies that they are a team. I quite like their wacky “get one over on the bad guy” schemes, where one of them will call out a plan that they seemingly rehearsed, and execute it flawlessly in cartoon fashion.

Make no mistake though, Quack Pack always comes back to Donald, and Quack Pack makes it it clear that Donald is the star. He’s the “protagonist” in a majority of the episodes, and the writers are a hell of a lot more interested in knocking him down so he can, despite all likelihood, save the day, like in “All Hands on Duck,” in which he returns to his Navy days and tries to be impress Daisy but screws up more and more. In “Snow Place to Hide,” Daisy knowingly uses her appeal to nab an interview (another example of Daisy being awesome), but Donald gets so jealous that it manifests itself into a green-suited wolf goading the duck on a rage (and that this wold has its own personality is icing on the cake; a hilarious moment where the wolf casually munches on croutons had me in stitches). And in “Ready, Aim… Duck” and “Long Arm of the Claw,” Donald actively lies and fucks up, drawing the ire of “The Claw,” yet in every moment that he finds himself in a safe place, Donald gloats and ridicules his pursuer with a sadistic glee that would be terrifying if it wasn’t so funny.

The best episodes blend Donald’s incredible behavior with the nephews teenage repertoire; while the show doesn’t exactly engage in the importance of family and relationships, the implication is there underlying the over-the-top breakdowns when such family relationships are in disarray. Donald is borderline evil in “Need 4 Speed,” where he fears his nephews being behind the wheel, but tricks them into building a car just so HE can drive it. “Tasty Paste” is the opposite, where Huey, Dewey, and Louie ignore Donald while they set off on their own, selling a gross-but-tasty goo. “Phoniest Home Videos” have the boys realizing they gone too far when they record their uncle performing stunts for money, especially when the producer tries to cut them out of the deal. “Ducky Dearest” has Donald becoming too upset over his parenting when he sees his nephews sneaking around; he thinks they’re up to no good when they’re just planning his birthday party, which has him going through more and more ludicrous crap to keep them in line. Quack Pack uses the insanity of its stories to show that the four of them work best as a family unit; if that breaks down, then there’s nothing left but chaos.

Which leads me to “Can’t Take a Yolk.”

Quack Pack isn’t afraid to play into insane cartoon tropes to prove a point, or to just have fun with some of its more crazier episodes. “Can’t Take a Yolk,” however, explodes beyond even the most over-the-top episodes into something else entirely, as it plays into the whole “retro” idea with a “before its time” deft hand that propels it to another level. It tackles the various ideas of practical jokes, punishment, and responsibility, where the nephews, after being punished for a silly gag, shirk their work detail via a random salesman. This salesman is not a thematic devil, a Faustian figment like Donald’s jealous wolf; he is simply a catalyst, a reason to introduce an de-aging concoction that Donald applies to himself by accident. And as the teenagers do their cliche teenager things – hit on a cute girl while a nearby bully intimidates him – in walks a younger Donald Duck. But he isn’t simply younger; his physical design and animation has been redrawn to his rubbery, stretchy 1930s designs, complete with sailor suit. The way the episode plays this is brilliant. It seems like a random, almost-another Donald Duck; it’s only as the teens realize its the real Donald do the viewers as well. Young-Donald is jerky, metaphorically and physically – abusing his antagonists and being egregiously mischievous like his old school self, and it’s a remarkable, self-aware, glaringly different moment that makes it a standout way beyond any other episode. Younger-Donald soon transforms into a baby, returning to the show’s current design and resulting in a Mindy-and-Buttons-esque escapade of the triplets keeping baby-Donald safe (and the episode has a weird, Invader Zim-type non-ending), but the middle of the episode is worth noting, suggesting a Quack Pack much more in-tuned with its premise and execution than one may believe.

Quack Pack is a smarter, funnier show than its reputation, but it’s not necessarily a better show than its reputation. That statement may seem at odds with itself, but it’s good descriptor. Not to say its a show filled with brilliant, subversive ideas within every cel, but it’s self-aware enough to understand what, exactly, it’s up against when it comes to its three “too cool for school” teens. It presents Huey, Dewey, and Louie as Poochie-fied as they come, only to poke and prod at all those “cool” elements, searching for ways to make them look like the immature fools they are (or, at the very least, attempting to give their behaviors some kind of base of humanity to build from, although that doesn’t always succeed). But it’s Donald’s show, and Quack Pack makes sure viewers know it: he wouldn’t have it any other way.

[PS: There are two elements I wanted to note. First, Quack Pack seems to be the second Disney Afternoon show that utilized title cards (the first being Timon & Pumbaa), which goes to emphasize Disney’s desire to go more cartoony and broad with its output. The second element is a bit more subjective, but Quack Pack seems to be the first Disney Afternoon show to have distinctive A and B-stories. Most of the shows I’ve watched had one main conflict that all the characters more or less had to deal with; here, there’s a distinctive line between the main conflict of an episode and whatever secondary conflict that another character would be involved with. I just thought that was interesting.]