Archive for category Writing

Family Feud’s “Success” is Built Upon its Irony

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Television, Uncategorized, Writing on May 1, 2014

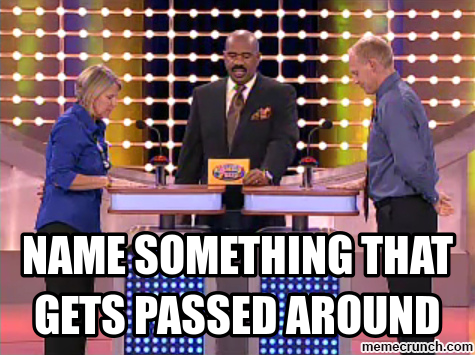

There are enough pictures and gifs on Imgur and Reddit that pretty much sum up the current run of Family Feud: questions clearly geared towards sexually provocative answers, lots of hooting, hollering, and laughter, and host Steve Harvey mugging wildly at the mere suggestion that, oh my god, how could seemingly normal people possibly come up with these answers? Remember that scene in The Cable Guy where Matthew Broderick was playing “Porno Password” with his family, growing more and more uncomfortable with each sexual suggestion? That’s essentially Family Feud.

The thing is, everyone’s in on the joke, with Steve playing the stuffed shirt role. I’m going to get into Steve Harvey in a bit, but for now, it’s important to understand that Family Feud has, at this point, stewed in its ridiculousness, of innuendos and gotcha-responses, and everyone is playing along. There was once a point where people played Family Feud to actually try to win. Now? You practically hear the assistant director urging families to say the most suggestive responses they can think of (or the most bizarre ones). Family Feud is less a game show than an elaborate comedy skit.

The internet has taken to it for sure. It’s a wonderful jpeg/gif smorgasbord, perfect for quote/expression/reaction captioning. In some ways, social media is what keeping Family Feud’s current run afloat, and the producers are obviously aware of it, coming up with some of the most insanely, specific questions they can muster up. Gone are the vague “Name something that you drink out of mug.” Now we have “Name something that gets hard when it gets cold,” and it’s hard not to eye-roll or facepalm at it. The show’s and contestants’ energy, however, is so contagious, you can’t help but watch along.

It helps that Family Feud has, at its core, a rock solid premise. Richard Dawson ran the show during its initial debut in the 70s, quickly making it his own. He spent literally the first ten minutes chatting and talking to the contestants, passing kisses to all the women, regardless of age, and shot the shit – which sounds boring, but Dawson’s charisma made it work. Dawson had a confidence, a presence that made him imminently likable, and he knew it, too. He also knew to control it, never coming off too cocky or arrogant. He was definitely one of the best game show hosts around.

“The Feud” was cancelled in 1985. It returned in 1988 with new host Ray Combs, who was passable but not nearly the presence that was Dawson (Combs ultimately committed suicide in 1996). The format changed slightly, dropping the extended introduction and focusing on a new “Bulleye/Bankroll” concept (this would eventually be dropped as well). The show proceeded to work through various hosts – Louie Anderson, Richard Karn, and John O’Hurley – all of whom were fine for different reasons. Family Feud itself, though, was a former shell of itself, a easy-going, early-morning game show with a fun format, where stay-at-home parents would shout the obvious answers at the screen in between commercials for cleaning products.

Then Steve Harvey began hosting.

To get why Steve Harvey “works” so well for Family Feud, it helps to really understand his career as a comedian. Steve Harvey’s routine isn’t really all that memorable or distinctive. His classic stuff was one might call “top tier” during the early rise of the young black comic in the early 90s, where HBO’s Def Comedy Jam and BET’s Comicview allowed African-Americans an opportunity to speak to a very particular “urban” viewpoint, when headlining The Apollo was as game-changing as getting top billing at Caroline’s, which boasted a heavy use of racial/sexual explicitness. Like its hip-hop counterpart, much criticism and controversy arose during this era. A lot of it was borderline racist, but there was a legitimacy in criticizing such comedians and their focus on comedy as shock value (he said nigga! she said she likes to suck lots of dick! and so on). There’s truth to the fact that so many young black comedians were blindly ripping off Richard Pryor’s success without grasping Pryor’s vulnerability and self-depreciation. (It also helps that Pryor’s routine took place during a very provocative era.) But it was a unique viewpoint nonetheless, and those voices were at least given the chance to be heard.

Steve Harvey was one of the breakout successes, post-Eddie Murphy (others included Jamie Foxx, Martin Lawrence, Cedric the Entertainer, DL Hughley, the Wayne Brothers, and Bernie Mac). They were all given TV shows and writing opportunities, and for a while they were managing a decent amount of success. In fact, Harvey, Cedric, Hughley, and Mac arguably reached their pinnacle with Spike Lee’s The Kings of Comedy, released in 2000, netting almost 40 million dollars on a 3 million dollar budget. Their routines were raunchy but pointed, speaking to a very specific crowd of African-American youths AND adults.

The rise of the alt-comedians in 2000 spelt the end of the “black comedian” so to speak. While the best black comedians found comedy in distinctive racial differences, alt comedians found comedy in “irony,” including self-aware distinctive racial differences. While everyone split off in different directions, Steve Harvey still had some success in the stand-up business, but began to turn towards a more religious viewpoint (one can’t help wonder if Bernie Mac’s death affected him more than he lets on), soon after refusing to use vulgar language, a la Bill Cosby. The Steve Harvey of today – the fixture of his radio show, his talk show, and his books – is more of a soft parental figure, a charming advise-giver and seemingly innocent, Christian, non-threatening black man who simply asks his audiences to let him into his home every morning.

So it’s funny to watch Steve Harvey host Family Feud. Harvey’s excessive mugging and over-the-top exasperation at the responses are, in their own ways, a load of shit. Harvey has said much worse during his 27 years as a stand-up comedian; he simply cultivated a much more home-spun, traditionalist “character” in the last six years or so. He’s no fool, though; the man knows comic timing, and he understands his role as a host. He’s not reading comments like “Give me a word a married man would use to fill in the blank: ‘I would _______ for sex’ ” without being self-aware enough to know that the show’s contestants would respond with “pay,” “lie,” or “kill.” Steve Harvey is playing his part. Everyone is playing their part, including the internet. It’s all a show within a show, a certain degree of irony that, in some ways, allowed Steve Harvey to indeed find his place within the alt comedy world.

Family Feud is the second highest rated show in all of daytime television programming (just behind Judge Judy). The core concept of the game show is strong enough to merit watching and playing along, but now its been given a jolt of pseudo-outrageousness with its questions and responses, exacerbated by a host who acts bewildered by it all but is clearly in on it. There’s nothing subversive here; we’re all in on the joke – the families, the producers, the viewers, the internet, hell, even the “100 people surveyed”. Family Feud, the game show, is really window dressing to Family Feud, the comedy. It’s not about the money. It’s about the fun. So let’s play the Feud, and lets try and keep it clean (and yeah, we won’t).

The 5 Reasons Why Turbo Failed and Ratatoullie Succeeded

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Film, Uncategorized, Writing on April 24, 2014

Today’s animated feature films are somehow both wildly diverse and unfortunately repetitive. Pixar, Dreamworks, Blue Sky, and Disney have engaged in brand new and creative worlds that, to its detriment, often star protagonists with wild dreams that inevitably come true, or battle impossible odds wherein victory lies in being true to oneself. It’s limiting for sure, but that doesn’t mean the execution needs to be lacking. In this case, Pixar and Dreamworks focused on those themes through two similar stories of small, anthropomorphic animals that dreamed big and would do anything to achieve those dreams, god dammit. And while Ratatouille had the heart and the chutzpah to be memorable and deep, Turbo floundered like a $200 million dollar joke. Let’s not kid ourselves: both concepts (a rat that wants to cook, a snail that wants to go fast) are ridiculous. Yet Pixar’s film draws us in, while Dreamworks’ film just pissed us off. Here’s why:

1) Remy’s dream is improbable. Turbo’s dream is impossible. The “rat” is symbolic of a kitchen that should be shut down. So Remy’s desire to cook in a professional kitchen is essentially up against what we as humans would categorize as healthy or sanitary. Remy is fighting against an admittedly justified stigma. In addition, he is simple a small rat from nowhere. No one, human nor rat, thinks much of him or his desire. Remy’s core obstacles are both personal and social. This makes the odds of his success extremely slim – but plausible. All he needs is someone to vouch for him (personal) and a location loose enough to allow that opportunity to flourish (social). When he gets that chance, he succeeds.

Turbo’s dream, on the other hand, is fucking stupid. It goes against nature and physics. I mean, it’s a idealistic dream, but it’s a magical one, akin to daydreaming about flying or walking through walls. Turbo – although I should call him by his real name, Theo – is wishing for something that literally defies science. I know that, in a cartoon, one can stretch the limits of the imagination and physicality of what is possible within the show’s world. But we’re not watching a film where magic exists “if you just know where to look.” Theo’s achievement of speed was a goddamn mistake, a freak accident that should have killed him. But no! Instead, he’s given Sonic the Hedgehog speed. What makes this particularly problematic is that, despite completely redefining quantum mechanics, technically Theo has received his wish. He wanted to go fast, and by “magical” circumstance, he achieved it. Why exactly does he need to prove himself in the Indy 500?

2) Remy’s knowledge of cooking is presentable and informative. Turbo’s knowledge of racing is lacking and irrelevant. Ratatouille is not focused on a rat that just wants to cook. Remy shows that he knows and understand cooking. From the appeal of mixing flavors to his intimate knowledge of the roles of all the chefs in a kitchen, the movie shows that Remy has put in his “10,000 hours” of study. Ratatouille is more than a film about a rat with foodie aspirations – it is a film about the wonders and appeal of cooking, the majesty and intricate details of how the best cooks around the world achieve their status. It is a hands-on look on cooking (the idea that one has to bribe the delivery man to get the freshest fruits and vegetables will never cease to amaze me). Remy’s tale allows the audience to examine a new, unexplored world that is cuisine.

Turbo has no such aspirations. Turbo tells us nothing about snails, or shopping plazas, or racing (at least Cars had the decency to explore a dying slice of Americana during the Route 66 scenes). Theo’s knowledge is how to work a VCR (a VCR?) when watching old tapes of various races. He knows the names of various fabricated race car drivers, but seems to lack the knowledge of how racing rules work. If he knows, the movie doesn’t let us in on the sport’s arcane secrets. There’s a scene where Theo finds a race car and begins to point out various intricacies of the machine. Yet he doesn’t explain what any of these parts mean or do (to be clear – he doesn’t need to explain it, but the film does). Turbo just wants to go fast, but he doesn’t put in the time or practice or study needed to achieve any goal from it. He’s allowed to race in the Indy 500 because a video goes viral for god sake (and it seems like he’s only allowed in if only to quell a rising mob). His achievements are bullshit.

3) Remy connections to the cast around him is meaningful. Turbo’s connections to the cast around him are tossed aside. As Remy runs into various characters his journey (his brother Emile, his father Django, his “partner” Alfredo, his “mentor” Colette, his enemy Skinner), they become an intricate part of his life, whether he wants to or not. These character aid or distract him on his journey, showcasing that despite his desire for cooking, there are various lives that he’s affecting, from inadvertently forcing his rat family from his home to closing down the restaurant at the end. His life, his existence, and his dreams have an impact on those around him, and vice versa. The causes and effects of his actions have consequences. There may be a happy ending, and there may be a bit of heavy-handedness (Alfredo being Gusteau’s son is as “writerly” as it gets), but overall the film understands the full weight, impact, and meaning of his pursuit.

Turbo lacks all of that. The only real piece of dramatic weight here lies between Turbo and his brother, Chet. Turbo seeks to make that significant by paralleling it with the relationship between the Dos Tacos brothers, Tito and Angelo. If the film wasn’t so sadly sincere, Tito could be considered legally mentally challenged. The film wants their dreams to seem both outlandish and within their grasp, but the sheer insanity of it is hard to buy, even by cartoon standards. Chet and Angelo are correct. Turbo and Tito’s dreams are accomplished by magic, a con, and a near-riot. And you know what? That wouldn’t be too much of an issue if their failures were given real dramatic weight. I mean, Theo got Chet fired, the fallout of which feels like something worth exploring, but his kidnapping by the crow changed the moment into a generic chase scene. The various talks between the realists (Chet/Angelo) and the idealists (Theo/Tito) feel perfunctory instead of necessary. Tito never considers at least having Turbo race for a bit of time to earn a nice cash cushion before making extreme decisions – no, he manipulates his Starlight cronies into handing him the Indy entry fee (if there was any time that a movie needed a “earning-money-montage” scene, it here). Chet’s absolute real concerns about a tiny snail racing massive, accident-prone vehicles isn’t a legit fear but portrayed like it’s just a “bug up Chet’s ass”. The movie portrays Chet reluctance to potentially watch Turbo DIE as lack of sibling faith, and this is terrifyingly misconstrued.

4) Ratatoullie has a well-developed set of side characters. Turbo has the worst set of side character I’ve seen since the Rescuers Down Under. [This point actually surprised me the most, as the previews made it seem like Turbo’s goofy side characters would be at least somewhat important to Theo’s journey (and the surprisingly great Turbo FAST gave them a simple but notable depth that is completely absent from the film).]

Remile, Django, Alfredo, Colette, and Skinner, have roles to play within Remy’s journey. They also have dreams and desires of their own. Remy’s actions interfere and intervene with their lives, causing fear, jealousy, frustration, and anger – but also wonder, amazement, encouragement, and happiness. Every character has their own individual goals – Skinner wants to sell frozen foods, Colette wants to be a real chef and not contend with a bumbling Alfredo, etc. The side characters in Ratatouille are appealing and driven by their own aspirations. They feel like characters that existed beyond Remy’s life.

Turbo’s side characters are pathetic. Other then Chet (and, if we’re stretching, Tito), the various characters exist solely to either denounce Turbo’s dreams or shout “GO!” during the climax. These are not people or characters. These are props, objects that are just there to give or take away something from Theo’s journey. The various people in the Starlight Plaza, Bobby, Paz, and Kim-Ly, literally just exist to give Tito money to enter the Indy 500. And the BIG NAME CELEBRITY SNAILS, which include Samuel L. Jackson, Maya Rudolph, and Snoop Dog, add nooooooooothing. Like, I can’t even stress this enough. They aren’t even comic relief, let alone mentors or advice-givers, or even “shoulder-to-cry-on” devices. Jackson as “Whiplash” kinda gives a half-hearted speech in the end (although it’s really tossed to Chet, who gives the REAL speech), but every single other character, be it snail or human, offer nothing (Rudolph’s “Burn” is a particular embarrassment. How much was she paid to spout terrible romantic dialogue at Chet at exactly three points in the entire film?). Turbo FAST’s first few episodes are flat because they’re literally rebuilding the character development from scratch.

5) Pixar visuals added to Remy’s story. Dreamworks’ visuals subtracted from it. So neither film here really spends a tremendous amount of effort with their visuals, to be honest, but at the very least, Ratatouille makes cooking, as well as the actual cooked food, look appealing. Emphasizing the value and importance of the food works to present Remy’s desire as, well, desirable. The appeal of the cuisine and the wonders of cooking isn’t exactly an excuse to open the animation floodgates, but this does allow Pixar to focus on specific details of the dishes and of the kitchen, with appealing whites and golds as the scenic “rewards” compared to the black and greens of the sewers, literally the lowest point of Remy’s journey.

Dreamworks has pushed visual boundaries with Kung Fu Panda and How to Train Your Dragon, utilizing frantic, fast-past action and breathtaking, soaring vistas respectively, in affect allowing audiences to re-examine what and how an animated film can showcase a particular scene (I think Dreamworks have been pushing this boundary more so than Pixar, but that’s a debate for another day). Unfortunately, the one thing that Turbo could have excelled at ended up leaving a lot to be desired. There’s not much going on with the designs of the snails (unless you find porn-staches the height of character design), and the humans are as flumpy and distorted as ever, which has become Dreamworks’ signature human design. But what about the racing scenes? Flat and perfunctory, lacking the panache and dynamics that fill practically every frame in KFP and HtTYD. Turbo’s final race, in particular, is surprisingly listless. The “marbles” appear only when Turbo has to drive through them. The camera is mostly static and eye-level, lacking intriguing swooping angles and dramatic pans and/or tilts. Nothing really emphasizes the threat Turbo is up against (although, to be fair, the film never bothers to suggest that a snail going against race cars is a horrifying ordeal). Everything is clean-cut and soft around the edges. Cars has more life to it.

Ratatouille focused on a degree of realism in the characters’ investment and succeeded. Turbo tried the same and failed. A movie like that would have been better served by emphasizing more ridiculous, goofier aesthetics, akin to Over the Hedge, The Emperor’s New Groove, or Pirates! A Band of Misfits (this is the approach that Turbo FAST is taking, to wondrous results). When it comes to small animals wanting to be like (rich, successful) people, you’re better off working with something that has some basis of personal connectivity, not idealistic miracles. For a movie about a speeding snail, Turbo is stuck between a rock and a hard place.

(Turbo’s tone-deaf mediocrity can be summed up by the fact that it mixed Tupac’s “Holla if You Hear Me” with Survivor’s “Eye of the Tiger.” That is unfor-fucking-giveable.)

Why The Action Cartoon Era Ended – And How We Can Bring it Back

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Childhood Revisited, Television, Uncategorized, Writing on April 17, 2014

Cartoon Network’s “DC Nation” is a joke. Literally. As of this post, the only cartoon aired in during this block is Teen Titans Go!, along with a smattering of various DC shorts, which are cute, but primarily entertaining to the Youtube crowd (this is not an insult – most of the DC shorts are great). Yet with Young Justice, The Green Lantern, and Beware the Batman cancelled, there is something sad in listening to the deep, booming voice announcing the intense, upcoming “DC NATION” during the interstitial graphic, only to be led to another wacky episode of Teen Titans Go!. Teen Titans Go! is actually a really funny show (albeit from the Adult Swim template); its hated reputation stems from how its goofy approach to superheroism is really the only thing on Cartoon Network that’s related to superheros.

I wrote about this briefly over on my tumblr, but I wanted to expand upon this more, especially in light of a recent comic post made by the showrunner to The Green Lantern, Giancarlo Volpe. I sort of wish Volpe had a bit more insight on the superficiality of the testing process, and the portrayal of Bruce Timm as a cigarette-smoking, too-cool-for-school badboy irks me at a gut level, but the directness of testing and its poor scientific procedures (everything is geared towards a specific outcome, from the lack of a control to splitting boys up by ages but not girls) is notable. If testing is a creative hell that animation showrunners are going to go through, then they’re already at a disadvantage. That being said, testing is only a part of the issue – toy lines, marketing, ratings, and word of mouth is another. Beyond that, let’s be honest: Cartoon Network was never committed to DC – that much is obvious. The general vibe among all the kids’ network is clear:

1) The action cartoon is dead. Of course, I’m exaggerating. But let’s take stock of the action cartoons currently on the air. There’s Ben-10, Legend of Korra [NOTE: as of July 24, 2014, Nick has removed this show from its schedule], Agents of SMASH (UPDATE: no longer on hiatus), Ultimate Spider-man and Avengers Assemble (which apparently is terrible), and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (and, if we’re reaching, Kung Fu Panda: Legends of Awesomeness). Note that everything has a strong comic element to it, save for Legend of Korra – none of the other shows listed delve into more serious, dramatic matters. (It’ll be a while before any of those cartoons pull a “The Man Who Has Everything.”) All of these shows have mixed reviews; Legend of Korra tends to have the most buzz when it airs, and even so, there have been issues with the current books. Time was that the major kids networks aired a block of action cartoons that mixed well with the comedy entertainment. Now, it seems like networks are scrambling to get rid of them – or, at the very least, to make them sillier and cartoony. I like my cartoons to be cartoony. I don’t like my action cartoons to be cartoony.

2) MARVEL killed the action cartoon. It’s the sad truth. The thing that made action cartoon thrive in the 90s was their ability to engage directly with their comic book aesthetics, delving to the more bizarre conceits like time travel, aliens, robots, and multiple dimensions. CGI was pretty much shit back then. Cartoons were where you went to see the cool stuff. Advancements in CGI took place in the 2000s, but movie studios still believed that superhero fare could only succeed with the right degree of campiness (give or take a Batman Begins). The seeds were planted when X-Men and Spider-man did well at the box office; Marvel simply doubled down on their movie properties, to great success. The kind of rich visual aesthetics that were only available on the animated screen were now visible on the big one. Of course, these films were PG-13, so children of all ages could see it, and they were so enamored with the films that the cartoons look like crap in comparison. It doesn’t help that the writers, producers, animators, and executives of the last vestiges of the action cartoons were amateurish, working with low budgets and dwindling ratings and mediocre scripts. As Marvel films took their products seriously, action cartoon creators didn’t.

3) Action cartoons didn’t help themselves. Going up against a behemoth like Marvel is a daunting task, but it’s doable. The cartoons didn’t do themselves any favors though. Marketing research has emphasized comedy – apparently this is exactly what kids want to watch. So everyone – from executives to creatives – got caught up in the need for their action cartoons to be a few action scenes inserted in the middle of a vaudeville act – heavy on the jokes, goofy on the visuals, and silly on the set pieces. Which, in all honesty, is fine. The last thing we want is the brooding male mentality to seep into our animated fare. That being said, not every episode and not every scene need to be built around a million punchlines. Action cartoons have room for drama, for heart, for real character development, and of the shows mentioned above, I hardly see it (again, save for Legend of Korra).

Beyond that, the actual action is questionably portrayed. The thing about action scenes is that they’re a physical extension of the dramatic beats of the current scene (it’s why thugs in Batman are dressed similar to the current rogue Batman is up against). Action scenes, like any scene in entertainment, needs to have a beginning, a middle, and an end. They need to have a clear goal and clear obstacles. What is the protagonist trying to physically accomplish? How are the villains actively trying to stop him/her? My rant against the second season of TMNT is antagonistic but clear, and I’ve questioned a few action scenes in Legend of Korra. Thundercats failed because it never took full stock of the seriousness of its premise; Beware the Batman took way too long to get to its admittedly intriguing story arc.

The future of action cartoons look grim, but there may be a way to save them. Primarily, we need networks willing to commit to them, in a way that goes beyond toy sales. From a critical perspective, though, action cartoons need to do the following:

1) Hit the ground running. You have about two or three episodes before you lose the attention of kids. So your first few episodes should hit some serious dramatic beats. Don’t only establish the world you built. Establish the characters we’ll be introduced to AND the kind of action scenes we’ll be seeing. Go big, don’t go ridiculous. It doesn’t have to be dark, but it does have to mean something. It has to be appealing. Blow their minds. And everything that you establish – action, drama, comedy, world-building, tone, and atmosphere – has to travel to the next few episodes. Beware the Batman had tonal issues and its rogue gallery had potential but never amounted to anything but various villains with different voice actors. All that has to be clear in the aesthetics, so make sure to —

2) Bring your A game (in storyboarding, animation, and writing). I find myself noticing more and more hiccups in storyboarding – the staging of the action is unclear and muddled, the animation tends to get lazy at time, and the writing feels forced and goofy. Both Beware the Batman and TMNT have passable action beats, but it’s obvious that both shows feel the need to have brawling actions scenes all the time, despite the fact that the heroes of these shows are ninjas and should be working more in the shadows. There’s a discrepancy here, when everything has to be working on all cylinders. The writing has to display why action is happening, the boarding needs to make every move and beat clear (why is he jumping out the way vs. running away?), and the animation should make every impact and near miss feel real and tense. That being said —

2) Stakes must be huge. Early and often. Thundercats’ pilot was dark, deep, and intense. It involved the murder of a leader of a kingdom, a kingdom that was isolated from the rest of the world and treated outsiders like shit, which was then followed by the mass genocide of said kingdom. Subsequent episodes pretended like that didn’t happen. It took till the second season before actually characters were developed, the genocide/hated-strangers-in-a-strange-land aspect was downplayed, and what started as a murky grey area quickly changed into black-and-white heroes and villains. (Probably due to that stupid testing?). The lesson we can learn from this is —

3) Don’t pander. Kids will know when you pander. Enough with mustache-twirling villains, charmingly-vague heroes, solitary female companions, and goofy sidekicks. How are we still working with this template in this day and age? I suppose that there’s plenty of marketing out that saying kids want to see goofy, comic versions of themselves in the characters on-screen. That may work now, but kids – especially those older kids – need to be challenged if we’re ever going to “earn” their respect for cartoons. If we can show them that cartoons can be as dramatically appealing and audaciously diverse as their live-action counterparts, we can work towards breaking down those “anti-cartoon” barriers. Do you know what else would help with that? Action cartoon should —

4) Appeal to adults and “trickle” the admiration down. Cartoons have a “trickle up” approach right now. Appeal to a specific demo – 6-11 boys mostly – and hopefully bring in girls, older boys, and ultimately, not irritate the adults who watch them with their children. Maybe we should work backwards. I’m not saying action cartoons should be super-serious. But maybe if action cartoons caught the attention of adults first and spread across word of mouth, then children (who want to be “grown-up” like their parents) would follow suit, watching it along with their parents instead of parents watching it along with their kids. That’s a bold call, but in some way, that’s exactly what Marvel is doing. I would argue that’s what Dreamworks managed to do with Kung Fu Panda and How to Train Your Dragon as well (in some ways, this is exactly what WB did with their DCAU properties in 1990s-2000). Applying this approach to action cartoons today may save them. With so few studios willing to commit, though, this most likely may not happen anytime soon.