The Secret of NIMH – (1982)

Director: Don Bluth

Starring: Elizabeth Hartman, Dom DeLuise, Derek Jacobi, Peter Strauss

Screenplay by: Don Bluth, John Pomeroy, Gary Goldman, Will Finn

We return to the realm of Bluth, that oh-so-strange animation director with the hit-or-miss filmography that inspires many an animator in the field, aspiring or veteran. While I previously vented my surprise over my disappointment of An American Tail, I at least acknowledged that his animation did indeed “work” somehow. I did come up short on detailing thoroughly on the movie’s parallel to the Jewish experience in 1890s Russia. (Although to be fair, 1) it is obvious and 2) Art Spiegeleman did it before in Maus, and 3) is irrelevant to the specific points I mentioned in the piece. But I digress.)

So now, I decided to jump back a few years to 1982 and explore The Secret of NIMH, which the Nostalgic Critic mentioned as one of the greatest nostalgic movie of all time (seriously, people, I’m aware of the guy—don’t have to constantly link me to him.). The movie did very well at the box office, grossing 14 million, double its budget, but let’s see if that secret is still as potent as it was back then.

NOSTALGIC LENS: Without any of the lighter, funnier, and/or wackier elements that I was accustomed to in animated form, I can’t say I remember liking this movie. Its seriousness seemed detrimental to what animation should be about—or so I believed. As I grew older and became much more accepting of darker, heavier films of the animated kind, upon thinking back onto this movie, another question came into my brain: what the f*ck did amulets and magic have to do with what basically amounted to a film about a mother saving her sick son? The script was reformatted with the fantasy elements to fit the 80s paradigm of popular young fantastical fare, but since I remembered so little about the film, I was desperate to 1) figure it out and 2) find out if it worked.

DOES IT HOLD UP: For the most part, yes. A solid 80% of it.

My main concern with this movie was whether or not the heightened maturity was warranted. When some sort of media forges its way away from typical family/children’s development, they automatically jump to an ultra-adult theme, utilizing sex, drugs, violence, or the grotesque (Heavy Metal, Conker’s Bad Fur Day). It’s only recently that companies like Pixar (and to a lesser extent, Dreamworks) manage to create films that do balance the perfect line between appealing to both adults and children (and genuine criticism). Back in the 80s and 90s, this wasn’t exactly the case.

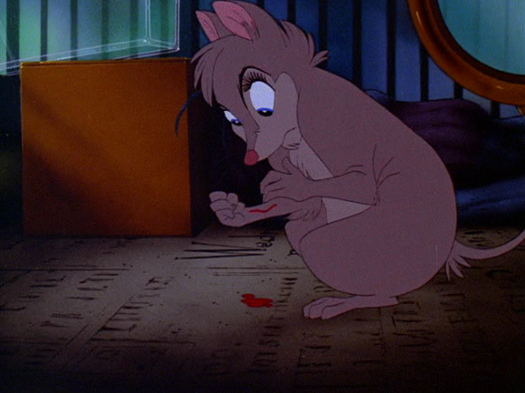

Luckily, The Secret of NIMH does indeed control its mature elements with a casual respect that works for the film, rather than against it. A mouse mother, whose child is sick with pneumonia, has to figure out a way to move her house before the farmer’s plow comes in and destroys everything, including her family. There’s a lot of interesting and complex story points here, but for the most part, Ms. Brisby is forced to do a lot by herself, showcasing a tremendous amount of bravery for a recently widowed wife. She even goes up against a churning plow aiming for her home. That’s hardcore.

The most noticeable delight about this movie is the calm, directed, poignant voice work. The voice actors don’t oversell their deliveries or push into exaggerated caricatures. They speak as if human, as if conflicted, struggling, concerned, worried, and panicked. They stumble over their words, stammer and stutter, talk over each other—speaking as if everything is real, not hyper-real. Check out this first scene of the movie, as Ms. Brisby speaks to Mrs. Ages:

In fact, subtlety is this film’s most brilliantly utilized aspect. The Secret of NIMH doesn’t push its plot or themes on the viewer (the humor, however, is another thing). Carefully and slowly, it becomes clear that the mice and rats and other critters of the farm are divided by class in some manner; Ms. Brisby, for example, can’t read that well, and the rats of NIMH, who grew intelligent through the experiments at the National Institute of Mental Health, become disillusioned towards the “lesser creatures,” epitomized by Auntie Shrew, who in turn distrusts the rats (and others “bigger” creatures) and their over-hyped brilliance.

Intelligence spurs the rats to try and move from the farm for better a better life for ethical reasons (they can no longer live like rats and steal!) but morally speaking, they still are SOBs. They don’t particularly care about helping Brisby or her family, until they realize she’s Mrs. Jonathan Brisby, the wife of the mouse who saved the rats from NIMH in the first place. (In fact, this fact is disturbing in a way. Mrs. Brisby isn’t given a first name—and being referred to solely by her husband’s nomenclature, coupled with the casual, borderline abuse she receives from other characters not named Justin is striking; being smart has little to do with being generous, and there’s no doubt in my mind that Bluth did that on purpose.)

A lot of what I mentioned is noted in this clip:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tsb9bPbI7PQ

With such beautiful, refined animation, excellent voice work, and rich, deep characters and backstory, it’s disappointing to note some of the film’s slightly weaker elements. The humor derived from Jeremy’s goofy antics is more problematic than funny (something that Brisby conveys very well through her voice), and his troubles in finding a girl is wrapped up so swiftly that, for a moment, you think it’s some kind of joke. In fact, the entire film’s ending is wrapped up so fast, it’s as if Bluth didn’t bother to write one, and just shoehorned something in to finish it. As for the fantasy elements? Well, they weren’t as distracting as I thought they would be, but you do get the sense that they shouldn’t have been there. However, they aren’t too awkward, except for the climax (which I won’t spoil), and Bluth works around them to make a credible film that has the view rooting for Mrs. Brisby all the way through.

IN A NUTSHELL: I have to admit I truly enjoyed this movie. I especially want to point out how well the sounds and music was used—and when the sounds and music weren’t used. The silent, quieter moments add much more to the movie than one might think possible, and when the score does pop in, you can bet it’s there for a reason. When watching Mrs. Brisby feed her ill son as her other kids look on, you can’t help but feel her plight. Indeed, unlike An American Tail, I was pleasantly surprised.

November 16th: Home Alone

November 23rd: [surprise entry!]

#1 by Jon on November 9, 2009 - 11:35 pm

Thanks for the review. I have to rewatch NIMH. All I know is my brother did a book review on the story in 3rd grade. I prefer subtlety and when it works in animation, the effect is sublime. Too often animators are forced to push animation to the max–like the Genie in Aladdin.

Don Bluth is certainly an inspiration.

#2 by kjohnson1585 on November 11, 2009 - 11:48 am

Jon,

I’m of both camps, really. Subtlety works well for Secret and other films like The Rescuers and Great Mouse Detective. Wacky stuff can work well, too– I’m a big fan of Tex Avery cartoons and (to a certain extent) Ren & Stimpy. The Genie was animated in excess to match Robin William’s excess, and, yes, we all know he’s annoying in any format.

— Kevin