By the time you hear Justin Roiland’s voice pop up in the third episode of Future-Worm, entitled “Terrible Tuber Trouble,” you can breathe a sigh of relief. There was a sense that this show, based on the weird and stilted interstitials and bumpers that aired between Disney XD shows a few years ago, was a rip-off Rick and Morty, Adult Swim’s wildly entertaining hit show. The intros to both shows are tonally similar, and so is the color palette, but the nonchalant comical approach to surprisingly complex plotting is the real, obvious point of comparison. Both shows contain sarcastic, over-the-top, droll alien creatures, and even the father figure characters of both shows are sad-sack loser types. It smells like intellectual theft. But with Roiland’s squeaky, stammering vocals added to the mix, you at least get the sense that the co-creator of Rick and Morty is in on the heist.

Let’s back up a bit. Having low expectations for Future-Worm is understandable. It looks like one of the many secondary shows that attempt to thrive on attention and (young) viewership through weirdness. Such a style was born in the cultural misunderstandings of Spongebob and the genuine understandings of Adult Swim. From Pig, Goat, Banana, Cricket to Pickle and Peanut, to Teen Titans Go, kids networks’ have attempted to create their own “super-weird, super-funny” animated hit, mostly to no avail (except Teen Titans Go, which is still a hit but feels increasingly irrelevant). Future-Worm stars a boy named Danny, voiced by Andy Milonakis (who is in his 40s), who is friends with an anthropomorphic worm named Future (voiced by James Adomian). The show, despite its weird set up and design, has the two run off on adventures across time and space and dimensions, mostly on a whim. This sounds like a generic kid adventure story. Yet there’s an off-handed, devil-may-care approach to their adventuring: the two tend to chart off when bored, or callously looking for dumb answers to dumb questions, or wanting to escape from basic chores. And now the heightened mundane purpose of their travels feels somewhat stolen from Rick and Morty’s various shrugged-off travels.

Well, if you’re going to steal, you might as well steal from the best, right? Rick and Morty is one of best shows ever, and with Roiland’s implicit approval of the show, Future-Worm is in good company. But even still, Ryan Quincy and his team manage to guide its influences and channel it through its own voice and direction, creating something that’s unique and weird, but also viciously clever – and viciously complex. From its interstitial beginnings, each episode of Future-Worm is divided into three parts, each of different lengths – twelve minutes, seven minutes, and three minutes. (The various lengths are familiar to animation fans: each type has been used before throughout animation history.) Disney probably mandated the lengths to shore up its burgeoning online/digital shorts package – the network most likely envisioned the show as simply-produced content to toss onto their Youtube channel or their Disney XD app (Disney feels like the only network that takes its online viewership seriously, as it now airs new episodes of shows online the same day those episodes are to be aired on television).

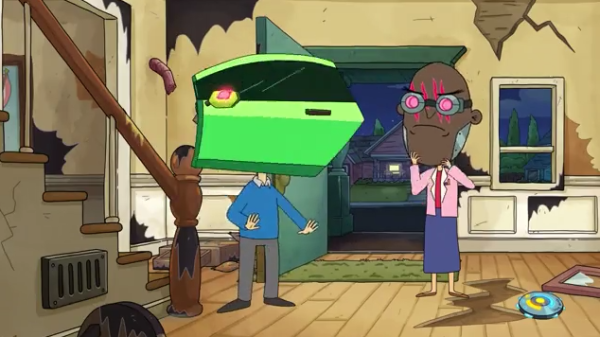

Quincy had something else in mind. Inspired by the post-credits tags in Rick and Morty, which play a comical, fast-and-loose response or commentary on the full episode itself, the Future-Worm team uses its unique structure to play around with the format and with the full marrative timeline of the show itself, while also using it a response or commentary to what came before it – or after it. It’s… difficult to describe, so it’s best to give examples. In the 12th episode, the first part ends with a weird gag in which an errant dimension-traveling device hits Danny’s parents in the head, transforming said heads into a car door and another head entirely. It seems like a random ending. But the second part tells the full adventure of what actually happened to the heads of Danny’s parents, which were transported to a “Death Race” in 3939. Or take the 11th episode: the second part tells a crazy story that Future-Danny (a figure separate from Danny himself) goes on, which involves people made of pliers trying to kill him. He escapes, fortunately, and the third part is Future-Danny trying to convince Bug, a friend of Danny, not to touch a certain pair of pliers, lest those same plier people track him down again. If that sounds confusing, it’s meant to be, but it’s also part of the value in rewatching episodes and tracking, even tangentially, the various timelines of what’s going on. Episodes connect in insanely temporal and atemporal ways, similar to Pulp Fiction’s nonlinear narrative; watch enough episodes, and it becomes clear that seemingly random segments are actually clues to its place within the “Future-Worm” timeline. Even then, the tone and energy of the show is so comedic and so devil-may-care (even the main characters don’t give a crap), that following along isn’t even that big of a deal (but valued if you do). There’s a whole semi-serious subplot involving lizard-people, powerful gems, and a prophesy, but Danny and Future-Worm can barely be bothered with it, even though it seems to be having some far reaching implications.

From part 1 of Episode 12, “Bug Vs. the Babysitter”

From part 2, Episode 12, “Doug Race: 3939”

Future-Worm is a complex, detailed, interlocking set of stories that combine into a slick, fully realized arc. Yet it also a silly, fun, episodic tale of two characters – a brilliant but lazy kid and a universe-travelled worm within a midlife crisis – who care little about that arc, and quite imply that viewers shouldn’t care either. Future-Worm is essentially a Croenburgean hybrid, a Rick and Morty clone spliced heavily with Venture Brothers’ detailed, go-for-broke, referential world-building, and Phineas and Ferb’s comically clever, winking, substantial fan service. Its slick, multi-layered narrative play is bolstered by animation leagues above its original interstitial visuals (courtesy of the ever-reliable Titmouse Animation) and a keen sense of narrative proportions within its three-part, sectioned structure. Yet unlike Rick and Morty, which approaches its narrative subversions or deconstructions from a world-weary, eye-rolling perspective (as if these well-worn tropes were such a burden to work, a notion that caught up with it in its wobbly, if still entertaining, second season), Future-Worm maintains a certain, idealized giddiness at such narrative opportunity. Future-Worm loves its storytelling, and loves making fun of its own storytelling, both engaging with and subverting it at the same time.

I’m somewhat reminded of The Aquabats Super Show, a short-lived show starting the infamously fun ska band that brilliantly, yet silently, “looped” its first season by connecting the final episode with the animated segments in its first episode, and connected the animated segment in the final episode with the live action of the first one. As I wrote about that show year ago, Future-Worm, in some ways, updates that premise. It doesn’t simply connect episodes, but interconnects them, while subverting them, deconstructing them, ridiculing them… and yet still can produce a sharp, tense episode of high stakes and nail-biting action. Watching Danny and Future-Worm battle it out with the Time Travel Council is funny but formidable, similar to how Rick and Morty faced the Council of Ricks in “Close Rick-counters of the Rick Kind.” And the similarities can not be ignored. But it’s the culmination of stories told and yet not told, of characters seen and not yet scene, of interlocking arcs that were experienced and soon will be experienced.

Or not. I mean, Amelia Earhart is there.

Stories are funny that way. So is time. So are the way we tell and consume stories these days. Future-Worm knows this, and uses it to its advantage.