Posts Tagged Film

Zootopia, Day 1 – How Did Zootopia Even Happen?

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Film, Uncategorized, Writing on March 7, 2016

You know, the fact that Zootopia is even happening is somewhat of a shocker. Over the course of this week, I’m going to get into a lot of things – the marketing, the line between cartoony/serious, the more “realistic” concerns that may crop up from the film’s aftermath – but today, I want to talk about how the type of film that Disney is producing here is kind of a marvel, for a lot of reasons. I mean, it isn’t as if Disney invented the anthropomorphic animal concept, or even the anthropomorphic movie itself (check out the comments here and here, who mostly scoff at the first trailer’s explanation of what anthropomorphism). The concept has existed since the beginning of time, and depictions of them have been seen in newspapers and animation reels since their conception.

You see, the concept of the anthropomorphic animal has gotten a seriously bad rap, primarily from two main reasons. One of which is obvious to you readers out there: “furries,” the name given to online fans of anthropomorphic animals, have for some reason been aggressively dismissed or avoided, as their affection for the concept has, in some people’s eyes, has translated to a perverse obsession. The other reason, which might be less noticeable to folks, is an executive-based, internal aversion to it. The general philosophy denoted “talking animals” as the preference of only very young children; older kids preferred human entertainment because they “relate” to it better. If you look carefully, the conflation of the first part (weird adults strong affection for talking animals) with the second part (talking animals’ primary demo of young children) has only double down on the overall stigma against any real, creative engagement with anthropomorphic animals as a whole.

That conflation came to a head back in the early part of the 90s. Now, this story is somewhat tough to research, as it’s mostly hearsay, and its source was Something Awful, which, in basic terms, was the 4chan of its day. Something Awful had enough clout to more of less “define” early internet subcultures, those of which mostly kept to newsgroups and webrings and IRC chats in relatively harmless fashion. So the story of a crazed fan who was obsessed with Babs Bunny from Tiny Toons Adventures, who ended up harassing Tress MacNeill at a fan convention, was egregiously hyped up and established as a prime example of those “perverted furries” in action. This not only tainted that fandom itself for years, it also turned made the “talking animal” concept persona-non-grata. as it were, from an industry perspective.

There was also a pretty fervent crackdown on most “adult” depictions of anthropomorphic animals, particularly in the censor-heavy, family-friendly, education-mandated politics of the 90s. Sure, The Simpsons and South Park were the prime targets, but even old cartoons from the 60s and 70s were heavily edited (particularly gags that involved suicide), and shows like Animaniacs and Pinky and the Brain were scrutinized to within an inch of their lives. Minerva Mink, the Marilyn-Monroe-parody bombshell, was the biggest victim, who’s obvious sexual inclinations in her first few outings were completely cut down to nil in subsequent episodes.

It’s important to understand that during this era, “shipping” and “slash” were not, in any way, “secretly” embracing by marketing teams. People who engaged in that kind of “fan fiction” were weirdos and losers, at least at that time, and the “anthro” fans were the worst of that lot. Add to it their history (by which I mean, the story of one single asshole who clearly needed help), and it’s clear that the talking animal concept was pretty much dead in the water. Not to say they didn’t still make cartoons with talking animals in them, but they were distinctly stylized and designed to be “off-putting” to say the least (Rocko’s Modern Life, Angry Beavers, Brandy and Mr. Whiskers).

In something of an ironic twist, Disney was probably the only company that was more or less okay with the talking animal concept throughout all of this. Their emphasis were more on their “Ducks” designs (Ducktales, Darkwing Duck, The Mighty Ducks, Quack Pack), but they were okay with branching out AND re-airing its past shows that showcased more nuanced portrayals of talking animals (The Wuzzles, Gummi Bears, Rescue Rangers, TaleSpin, and Gargoyles, to a certain extent). Part of this was because Disney had its own stringent S&P standards, part of that was also that, as a company not so hammered by networks standards (they owned ABC but that company mostly managed itself), they could do whatever it wanted. Disney did abandon the talking animal concept not for any real social-pushback reasons, but because they wanted to produce more content based on their movie properties. (Which had its fair-share of talking animals in them, to be clear).

So, in that regard, it makes sense that Disney would be the company to release a film like Zootopia, what with its clear allusions to Robin Hood, a film that also (for lack of a better term) encouraged the anthropomorphic fandom. But it took a while for it to catch on: in fact, it took an entire social/cultural transformation on the perspective of fan/geek culture in general. Geek culture, on the whole, was regulated to mostly comics and message boards, up until Iron Man hit theaters (well, to be more specific: Blade was the catalyst, Spider-Man/X-Men were the support, Iron Man was the confirmation). That began the current wave of superhero films that, at this rate, will never end. But it also brought geek fandom to the forefront, and all of its more questionable aspects.

Yes, that includes shipping, slash, fan fiction, social media, and obsessions over franchises. Disney tried to slip into that realm with Tron, but after that failed, they just went ahead and bought Marvel and Star Wars so they could do the heavy lifting. With Pixar more or less engaging in the “award-winning” realm of animation, and Frozen and its princess-fare winning over girls, Disney Animation was free to “experiment” as it were. And that’s essentially was Wreck-It Ralph was.=: an experiment.

Think about it: Wreck-It Ralph, too, was a movie that really shouldn’t exist, what with it’s heavy video game-filled world and its abundance of video game cameos. Nor should it have been a hit, since video game movies were also mostly ignored by the entertainment business at large. But Wreck-It Ralph was not only made, it was a hit, proving that geek culture’s financial power expanded way past superheroes (we’ll see how far when Halo, Assassin’s Creed, and Warcraft are released). Disney, to a certain extent, has always knew this, but never really had to chance to push it too much (the naughts were a tough decade for the company, financially). Considering that “anthropomorphic animals” were always something it had in its back pocket, it makes a certain amount of sense that they’d try to pursue it again.

It was Dreamworks, strangely enough, that most likely triggered Disney to greenlight Zootopia. Similarly to how Blade/Spider-Man/X-Men triggered the superhero glut, Dreamworks’ Madagascar/Kung Fu Panda films quietly created an opening for anthropomorphic animal films to make a roaring comeback. Both films were financial hits (the latter, the more critical darling), but the more casual response to the films, particularly the more mature discussion around Kung Fu Panda itself, probably sewed the seeds for Zootopia to come to fruition. In this example, Madagascar would be the Blade, Kung Fu Panda, the Spider-Man. If early word of mouth and reviews are to be believed, than Zootopia will be the anthropomorphic equivalent of Iron Man. (Also, note: the sheer number of animated movies coming out this year starring talking animals of some sort. This cannot be a coincidence.)

Even then, it took some convincing. Apparently it took some convincing for Disney to approve Zootopia, the main holdout being John Lassater himself. This would make sense, since Lassater would have been around during the time of the Babs Bunny incident. But even he couldn’t ignore the signs: the rise of geek culture, and with it the rise of internet fandom; the successes of Wreck-It Ralph and Kung Fu Panda, and the critical receptions (and acceptance) of films so steeped in fandom-loving sentiment; the power and appeal of fandom itself, and the growing attention (for good and for ill) of the anthropomorphic concept, the thing that Disney itself has more or less defined, and is getting back to defining. Tomorrow I’ll discuss how Disney’s marketing managed to control the dialogue and win over skeptics, and how it’s easing its way back into the anthropomorphic market.

The Problem of the Gendered Narrative

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Film, Television, Uncategorized, Writing on August 31, 2015

Buzzfeed got the animation world talking quite a bit with its recent article “Inside the Persistent Boys Club of Animation.” And while it fits perfectly within the contemporary, aggressive call for more women (and PoC) creatives in the entertainment business – a call I agree with one hundred percent – it’s Lange’s exploration of how certain genders depict certain types of narratives that has my interest piqued. She writes:

And that difference shows up on our screens. According to a 2012 study from the Geena Davis Institute, female characters made up 31% of speaking characters in primetime children’s shows — less than a third. Only 19% of children’s TV shows had an approximately equal number of male and female characters.

Later:

And this mentality is drilled into women studying animation. In a class at CalArts, Cotugno recalled, an instructor lectured on the difference between “feminine” and “masculine” story elements — “which is a little hard to describe, mostly because it’s fucking bullshit,” she said. Elements such as linear storytelling and big external stakes were “for men,” while relationships and emotional storylines were “for women.”

The whole thing is a must-read, but those two paragraphs struck me because it clarified a lot of thoughts I had about how women characters function in cartoons. As you can tell, I watch a lot of animated “stuff,” and what’s weird is how, overall, male characters are fairly developed from the start while women characters tend to fluctuate. This is in extremely broad terms, but part of me wonders if the kinds of stakes that we’ve inadvertently gendered is a bigger issue than just poor, outdated teaching ideas. It’s a top-down problem worth exploring in deeper detail.

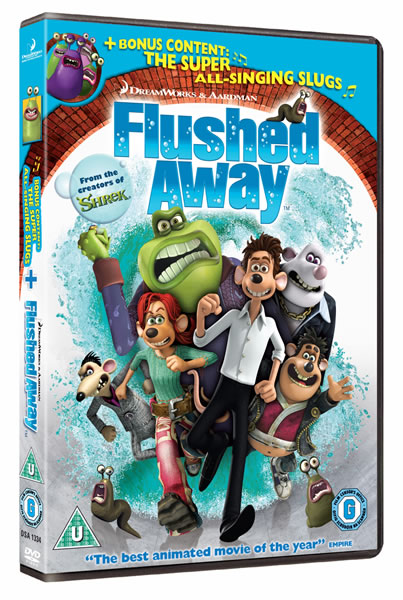

A few weeks ago, I watched Flushed Away, an Aardman/Dreamworks collaboration that did mediocre at the box office, so as to assure that Aardman and Dreamworks would never work together again. It was a film that garnered mixed to poor reviews, but with my current run to catch up on animated films, I thought I’d give it a go, with the requisite that I would Twitter rant about its flaws. And while it was flawed, I was struck by how fascinating the “secondary” character, Rita, was. Rita was an extremely strong, well-developed presence, much more than Roddy, the titular main character. She was voiced by an extremely game Kate Winslet, and had the tenacity of Lara Croft with a warm, engaging emotional appeal like Pearl from the early episodes of Steven Universe. With a few tweaks, Flushed Away could’ve been an precursor to Mad Max: Fury Road – a generic film masking a strong, almost-feminist bent, in which Rita was the real star and Roddy, at best, an annoying sidekick. I can’t tell if it was Dreamworks or Aardman who missed that narrative, but it goes to how we perceive certain narratives and gendered character roles within a piece of entertainment.

I’m not sure how anyone, within the pre-production period of a film, not look at the development of Rita and recognize that she is the star, full stop. She possesses the “big external stakes” and the main thrust of the film is built upon her goals. Yet placing Roddy as the film’s lead is just part of the overall trend with large-stake narratives (he’s front and center on the DVD cover). There are plenty of great female characters, but they feel isolated, the lone feminine figure in weirdly, excessively male-driven worlds. Yet there’s a little bit more going on here, because opening up certain types of characters to the feminine sphere might cause a bit of hand-wringing. In the past 35 years, how many villains, or even antagonists, in films have been female who aren’t mothers? And what about the henchmen?

(The role of henchmen is worthy of a talk of its own. From second-in-commands to the lowly grunts, being a henchmen is a seriously male-driven occupation. How much of this is Standard and Practices, though? How much of this is the overall fear of placing female characters in positions that is primarily set up for bumbling and red-shirting? Because animation has become a medium driven to appeal to kids, the fear is that placing women in roles that usually get abused would be disrespectful and cause kids to follow suit, but that’s damaging to both boys and girls, since it ignore girls completely as well as encourages that kind of disrespect among boys. But I digress.)

One of the most important aspects of the early Disney Afternoon cartoons was its general focus on appealing to a broad, mixed fanbase. Both The Wuzzles and Gummi Bears clearly were looking to appeal to both boys and girls, but the focus shifted as Ducktales hit the airwaves. The shows that came after – Rescue Rangers, TaleSpin, Darwking Duck – had enough content to keep young women hooked, but they were mostly the fare of boys. In addition, the grouping dynamics of the primary cast of cartoons shifted. Girl-to-boy ratios went from 2:3 to 1:3; if a show present a group of mixed-gendered characters as the show’s leads, it has never provided more girls characters than boys. Mostly all kids networks mimicked this, despite hit shows like The Powerpuff Girls showing the potential of female character-driven shows. And really, not since Hey Arnold! have a show really explored a rich, varied group dynamic.

It’s clear that gendering narratives is both harmful and lazy. But what is insidious is how ingrained this idea has become. Not only are certain “types” of stories have to be told from the perspective of boy characters, but the minute details of those stories have to fit certain parameters. There’s very little focus on emotions or vulnerability, although that is getting better: Wander (Wander Over Yonder), Steven (Steven Universe), and Gumball (The Amazing World of Gumball) are much more prone to wearing their emotions on their sleeves, and acknowledging that those explicit feelings are valid.

Female characters are getting better as well. From the Mane6 of My Little Pony to the spunky silliness of Star from Star Vs. The Forces of Evil, TV animators are not only allowing women characters to star as leads, but to engage in their audacious adventures while also letting their emotions out for all to see. The wall limiting what types of stories one can tell with gendered characters is changing, albeit slowly, without necessarily falling into the kind of traps that hurt other narrative forms – restructuring the “Strong Female Character” as “Masculinized Female,” for example.

The biggest problem seems to be that in our attempts to push down gendered limits in entertainment, we’re pushing more and more into segregated content. Strong, singular leads are great, but shows that demand broad, mixed casts struggle intermixing gendered characters, from the testosterone-driven brotherhood that is the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, to the female-coded Gems of Steven Universe. Which, inherently, is fine, but it hinders creative insight into how a full group of boys and girls can manage a situation and keep true to themselves. It’s a top-down problem, again – there’s an upcoming all-female Ghostbusters and an all-male one coming soon. There’s an all-female Transformers on the way, along with an all female DC-superheroes series coming as well. Genevieve Koski over the (sadly now-defunct) wrote about the problem with the “distaff counterpart,” but at the level of younger viewers, it implies that not only are the two genders markedly different, but that they can’t even interact without some kind of problematic “Mars/Venus” dilemma, as if two different genders thrive in two different parallel universes.

These ideas, taught to us as kids, have become de facto lessons, that the decision of creating a certain character male of female automatically define the basic beats of a story – beats that cannot embrace multiple genders in any narrative way. An evil force that wants to destroy the world has no ties to male or female characteristics, but more often than not, male characters are the heroes, thematically linked to paternal-leadership-protector themes. For the few women heroes that save the day, they’re linked to more emotional-maternal-caregiver themes. And it’s that core, basic thinking is more troubling than we realize. Thematic resonance is important to all narratives, but not when they’re built on vague stereotypes and gendered segregation.

Why I’m Okay with The Lego Movie’s Oscar Snub

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Film, Uncategorized, Writing on February 19, 2015

The most talked-about Oscar snub was for Selma’s exclusion from the Best Director and Best Actor nominations. Surprisingly, talk over The Lego Movie’s Best Animated Picture snub seemed equally controversial, perhaps even more so, particularly over at The Dissolve. And while outrage continues to follow it around, with directors Phil Lord and Christopher Miller tossing back-handed insults towards the Academy for their perceived neglect, I can’t help but think that, perhaps, the Oscar voters may have gotten this one right.

To be clear, award season has always been, and continues to be, an elaborate stroke-fest: self-servicing, brown-nosing, self-celebratory crap. Most people know that most of these awards are nonsense, and the outrage only really feeds into the season’s insatiable love for itself. That being said, some films are noted to be shoo-ins, particularly with the Academy increasing the number of films that could be nominated. The Lego Movie was a critical and commercial success, so it just seemed like a no-brainer that it would win Best Animated Picture, let alone be nominated for it. Yet the Academy chose: Big Hero Six, The Boxtrolls, How to Train Your Dragon 2, Song of the Sea, and The Tale of the Princess Kaguya, leaving off The Lego Movie, much to the chagrin of many people.

Not so myself. While a majority of the world saw the film and loved its clever take on the Chosen One concept, along with its comical/thoughtful take on the Lego world, I saw just a perfectly fun, cute film that nevertheless fell for the same kind of tropes that Chosen One films tend to fall into, via animation that did exactly what it was supposed to do. The Lego Movie had fun with its premise but it’s difficult for me to agree that it did anything novel with it – save for an inspired climax. Beyond that, though, it possessed the kind of simplistic gags that often fill animated kids films, troubled with actors unsuited for voice over work, and the kind of average, Joe Campell-esque pacing that most critics would pan in other films, animated or otherwise.

Not to say it wasn’t a bad film at all! It reminded me, in fact, of Cats Don’t Dance and Over the Hedge: two animated films with comically clever group dynamics and fast-paced sequences. Yet while The Lego Movie wore its satire on its sleeve, Cats and Over were a lot more subtle about its commentary (the former’s endearing homage to 40s and 50s musical animated shorts; the latter to the encroaching suburban blight on the natural environment). I love those films but I would never say they deserved Oscars, and The Lego Movie was basically a trumped up version of those films. The Lego Movie is also built on a slightly recent batch of animated films which seek to “subvert” certain tropes of animation plots – only to lean into those tropes anyway. Shrek sought to break down the happily-ever-after ending of generic fairy tale stories, only to end with exactly that, albeit on the ugly-orge side of things. Frozen tried to break free of love-at-first-sight storytelling when it comes to princesses, only to suggest the second handsome guy you meet is totally fine. And The Lego Movie, while exposing everyone to be potential master-builders, still ended up with Chosen One Emmet to be the master-builder that saved the day.

I’ve said this before, but most modern critics tend to be terrible at analyzing animation as a whole. They’ll know the big names of animation – your Brad Birds, Hayao Miyazakis, Chuck Jones, Tom Rueggers – and if you’re lucky, they might be aware of Genndy Tartakovsky, Lauren Faust, Henry Selick, or Pendleton Ward. Critics are not voracious viewers of cartoons – the insane work of Tex Avery, the character-focused oeuvre of Paul & Joe, the wacky excellence of Mark Dindal, or the brilliantly satircal cartoons of Jay Ward. The latter, in particular, was built upon satire and subversion, with the various bits introduced in Rocky & Bullwinkle utterly annihilating generic animation tropes, and this was back in the 60s. Watching a lot of cartoons is tricky – it’s time-consuming and requires a certain degree of patience – but I think to truly understand cartoons, the various approaches to visual representations, requires a certain commitment that many critics fail to take part in.

So of course The Lego Movie seems like some sort of top-notch brilliance to them. And, to be fair, there is a lot to like about it. But in the whole scheme of things, The Lego Movie, with its reliance on generic rhythms and faux-subversion, all within (and let’s be blunt here) an obvious toy-based corporate tie-in, is pretty ordinary. Some people point to the film’s animation as a celebratory selling point. I agree that the film’s visuals were perfectly tailored to The Lego Movie’s sensibility, but to be honest, the film did exactly what it was supposed to do. It committed to the “Lego” look, with the movements and pacing akin to the limited movements and pacings of the actual toys, but it actually didn’t do anything interesting with it. No sharp montages. No unique comic/dramatic visuals. Nothing about the animation pushed the film aesthetically.

How to Train Your Dragon 2 (the only nominated film I managed to see this year, an unfortunate blight due to financial issues) had its flaws, too. And while I don’t think it should win, I do think it’s a stronger film than its reputation, with its commitment to its central family unit (before its torn asunder), its unique dragon personalities (Toothless has never seemed less adorably playful), and its mastery over its visuals and art designs. Just the scene where Hiccups reunited father and mother singer their courting song to each other is powerful stuff, with its swooping camera angles and play on the area surrounding them. It’s an insular, personal film that struggled against its bombast, action-fest second half, but it understood the importance of look, feel, and meaning, in terms of the situation and the characters. In comparison, The Lego Movie was about the flair, the self-awareness, the subversion (that never was). It’s a movie that leaned hard on the idea of being a self-aware toy-product, and while it did do a fine job with that limitation, it still was a self-aware toy product. Of course, this allowed for a wonderfully strong, climactic third act, but that’s just the third act. Two-thirds of the film are still flat, generic, run-of-the-mill animation and pacing, with mediocre gags, less-than-average voice work, and exciting-if-passable action.

The next few weeks I’ll be working my way through the rest of the nominated film as they drop on DVD. With The Lego’s Movie snub, and the various flaws that How to Train Your Dragon 2, The Boxtrolls, and Big Hero Six reportedly possess, perhaps this will allow the outliers Song of the Sea and The Tale of the Princess Kaguya a larger chance to win (or maybe that this was just a weak year for animated films). But while The Lego Movie has strong moments, I can’t agree that it’s worth a nomination nor even the Oscar itself. It’s fun but slight, ambitious but generic, fun but fluff. Admittedly I do have issues concerning the “Lego-fication” of a lot of entertainment nowadays, but even still, I wonder why it takes a product-film to bluntly emphasize the power and wonder of unbridled creativity, even though, particularly with animated films, that should be the default mindset. (Perhaps it is the lack of openness when it comes to critics and their approaches to animation – film, TV or otherwise – but that’s an argument for another day.)