Posts Tagged Writing

Some Thoughts on Gamergate

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Uncategorized, Video Games, Writing on September 9, 2014

My name is Kevin Johnson. I am a gamer. I am a feminist.

I have issues with gamers. I have issues with feminists.

I. A Case Study

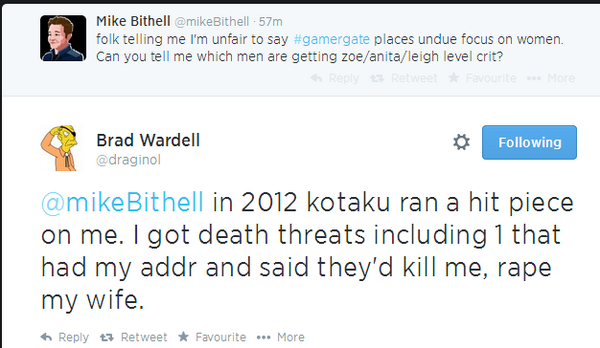

Among the many, many things being tweeted and written about concerning #Gamergate, this was among them:

Curious, I took a look at the so-called hit piece.

I’m not sure if the definition of “hit piece” changed over the years, but what I see is a pretty cut-and-drive piece of investigative journalism, exploring the fallout of a disastrous game release. It involves a lawsuit between Alexandra Miseta and Brad Wardell, of claims and counter-claims, of dismissals and motions to block them. It doesn’t make any side look too pretty, and most likely this information was discovered when Kotaku sought to investigate why this game failed so miserably. This is on par with investigations, really. Watergate, which Gamergate derived its name from (and so, so many other misguided large-scale scandals), began with two reporters looking into a really odd break-in.

If Brad’s response is true – and, for the full purposes of this piece, I will assume all accusations of rape and death as true – then already we see the trouble. It’s absolutely horrific, but characters of ill-repute and good-repute has gotten threats as well – Bernie Madoff, George Bush, Barack Obama, Hilary Clinton. All of these threats are indeed awful and should be treated with the utmost seriousness, but I noticed that Wardell’s wife received the rape threat, who, for all intents and purposes, is completely innocent of the lawsuit. Oddly enough, in this overall discussion about how much misogyny has to do with this scandal, many supporters of Gamergate circulate this tweet to support their cause. But right there, with the rape threat of a woman not involved in any way with this situation, pushes back against that argument. In addition, its probably safe to assume a “gamer” was the one who made that threat, by which I mean that a person who is familiar with Kotaku and the piece, and therefore has some intimate relationship with games. He is probably male, based on the idea that a woman threatening to rape another woman is rarer still, but I do not discount the possibility. In either case, a threat was made against someone, a female someone, far removed from the lawsuit, and by every journalistic definition, that Kotaku piece is far from a hit piece.

I’m also aware of Mike Bithell’s initial tweet. It’s not necessarily too hard to look for various places where death threats have been lobbied towards male writers, particularly when they review socially popular games and deem them less than perfect. And as Gamergate takes speed, there is a tendency for its proponents to focus solely on the initial harassment and not look, at least partially, in some of the more pressing issues that Gamergate supporters are concerned about – the overall improvement of game journalism (the core of which, to be clear, may be different than what most Gamergate supporters are actually advocating for).

This entire Gamergate situation, from the outside looking in, is vile and nonsensical, a “much ado about nothing” wave of gibberish among stereotypical gamers. Inside, however is a powerful stalemate of massive cultural forces, of gamers pushing against their stereotypes as typical male angry youths; fortunate game journalists’ defensiveness against a growing populous voice desperate to be heard; feminist forces demanding equal and improved treatment against a contingent of males (and females) who believe that such a thing is, and should be, no big deal. The civil voices trying to make some sense of it all are drowned in violent, sexist threats and the mass shunning of a culture who will not be shunned. And in the midst of it all, it’s gaming and gaming reporting which suffers.

II. The origins and fallout of Gamergate

At this point it’s pretty much agreed what prompted Gamergate, but the overall response to that prompt is massively distorted. Zoe Quinn created a game called Depression Quest, which got generally good reviews from most gaming sites. However, it was revealed that she was dating a writer from Kotaku (information divulged from a ex-boyfriend), which prompted some concern from many readers of the site about biased reported. The Kotaku senior editor swore that no ethical injustice has occurred (and the writer was not the one who wrote the review on Depression Quest), but the flood gates had parted. I should also mention that there’s a sense among gamers that Depression Quest is actually not that good (or perhaps worthy) of a game, which runs counter to the reviewers’ high praises, and that seems to have caused its own bit of consternation.

Not quite related, but significant nonetheless, has been the most recent release of Anita Sarkeesian’s Feminist Frequency program, which discusses various sexist tropes in video games. I don’t one hundred percent agree with Sarkeesian’s points, but sexism in gaming, like most entertainment sources, comes from laziness more so than misogyny; the question she, and many others, are asking is why, when given the lazy choice, do we resort to utilizing women in half-handed fashion.

The combination of these two events created an flaming uproar, the fires of which was stoked by things like the JonTron vs. Tim Schafer argument on Twitter, and reports that both Sarkeesian and Quinn had to flee their homes and report to the police after some of the rape and death threats grown too close to home. A curious thing happened; after Sarkeesian made her report, she asked for a donation to her show. This seemed to be the defining moment that Gamergate went from a typical gamer rant against encroaching censorship into all-out war against game writers. The conflictual threat of fearing for your life followed by the request for money had many, many people calling foul. Now the argument was about game writers, critics, and journalists using their experiences and connections to make extra, easy, and manipulative money off corporate kickbacks and the hard work of gamers. There’s definitely an air of sexism here, but there’s a hint of social unrest, too – game journalists, who’s credentials as writers (let alone journalists) are questionable, sitting in their rooms or offices and playing games for free and writing opinions as law while gamers are shelling out $40-$600 or more bucks on games, software, hardware, and DLC to have their voices unheard. Sure, most game journalists aren’t paid that well, but they DO receive kickbacks, even if it’s in the form of free games and invites to events, and most gamers aren’t exactly financially well off. Nothing says this more than E3 coverage, which tends to have more people writing about HOW MUCH WORK THEY HAVE instead of actually working.

Like it or not, Gamergate is a thing. It’s lots of things, really, but it’s a lot of accusations and misunderstandings, not only of what feminism is, but what journalism is, what writing is, what “game culture” is, and what “game culture” means to millions and millions of fans. Times are changing, and how we discuss games is changing, but there are those on both sides of the aisle who refuse to budge; the gamers sick of the discussions of sexism, the writers tired of being lumped into the “gamer” stereotype, the gamers tired of being lumped into the “gamer” stereotypes, and everyone else trying to get in a word edgewise about minority/LBTQ representation, about labor issues and improving the overall game and game market, and about finding information on the next big game coming out. It’s that unwillingness to budge, that inability to acknowledge that there are serious problems with gamers, game journalism, and feminism, that caused Gamergate to reach this point.

III. The problem with gamers

I am a gamer. I make no qualms or parameters on what “real” gaming is or what a “real” gamer plays. Gamers play games, no matter how hardcore or casual. I might say that gamers, at least somewhat, should be interested in broad gaming events or releases, but that’s hardly a qualifier. Gaming enthusiasts or gaming fans, on the other hand, I think should be interested in, if not the variable genres of games available, at least in the way we talk about and discuss games to improve them and their cultural cache. The question is how to do that, specifically, but the discussion is a good start. There are those who can discuss the specifics of multiplayer, or the details when it comes to glitches and graphical prowess. Those who do frame-counts in fighting games, and can argue to death how removing certain RPG elements from various RPG sequels were a good or bad move. And, as much as gamers loathes it, discussing the roles of females or minorities in gaming is part of that.

Feminist and social critiques are part of literature, theater, film, and TV, and if gamers are strong advocates of gaming as art, and I am, then you have to accept that element of criticism as, if not agreeable, than at least valid, as part of the overall aesthetic of gaming. If you aggressively disagree with the criticism, that’s fine. To deny it any sort of legitimacy is a problem, though, and decreases gaming’s role as legit art. To aggressively push tactics that threaten the well-being of such feminist critics, or even to go out of one’s way to name-call, or create games and videos that de-legitimize these feminist critics, is another matter entirely: it’s petty and vindictive, and has no place in any form of pop culture, let alone gaming. There are those who are there claiming such antics are in place to expose feminist critics as self-serving, false victims catering to a gullible audience to make money. The problem here is two-fold. 1) Ignoring the critique to attack the author does little to actually de-legitimize the critique itself (this form of attack is what is called “ad hominem”), and 2) misunderstanding the financial burdens of the (most likely) freelance writer; asking for money in a kickstarter/patreon world is a legal form of revenue, both by the state and the federal government. Gamers who understand the financial struggle in their daily lives seem uncomfortably upset with writers looking through other avenues to earn money, particularly on the backs of criticisms they heavily disagree with. Unfortunately for them, this is a free country, so capitalism told me.

What makes it hard to get behind the current role of gamers is how this attitude is more or less geared towards women. They will tell you to the death that it’s not, but considering that Gamergate began specifically with two incidents involving women, it’s hard for that argument to gain traction. Is there a male-based incident that is also riling up gamers concerned about journalistic integrity? Perhaps, but it hasn’t crossed my way, and I am open to suggestions. I suppose we could point to the JonTron/Tim Schafer incident, but that had been triggered specifically by a Sarkeesian video. What I’m asking is if there is a specific, male-based incident outside of any association with Quinn or Sarkeesian that also brings to light the corruption of games journalism. I’m curious to see it.

Gamergate supporters will often emphasize the fact that those people who have harassed Quinn, Sarkeesian, and prominent game critic Leigh Alexander (the subject of the above picture, where there seems to be a gross misunderstanding of Time’s Terms of Service, and a failure to note that Alexander’s piece is actually in the site’s op-ed section) are in the minority. In fact, with a bit of clever and distinctive use of carefully crafted screengrabs, they will declare any vile outburst against them as forms of harassment; that they are the victims, being stifled in their efforts for gaming journalistic transparency. This is fantastic work; Fox News is probably nodding in approval. As Don Draper said (a character whose entire life is constructed on a giant lie) once said, “If you don’t like what’s being said, change the topic of conversation.” Which they did, quite swimmingly. There’s little concern over whether Quinn or Sarkeesian are actually okay after their harassment; instead, Gamergate supporters are demanding proof of this and the police reports that were filed (interesting enough, no one demanded proof of Brad Wardell’s accusations). Meanwhile, in an scenario where attitudes and sensations are already running high, outbursts where Gamergate supporters are being told to fuck off for being described as said, white, basement-dwelling men (more on this in the next section) is craftily retooled as examples of harassment of the opponents. Never mind the real fact that telling someone to “fuck off” is, legally and ethically, not harassment – simply provoking the opponent via seemingly harmless ways to anger, in order to utilize the angered response as the “real” attack, is political craftsmanship.

However, when there is overwhelming evidence of gamer harassment, like what occurred recently, when someone attacked Sarkeesian with pictures of child pornography, craftsmanship rears its head again. Still, no one asks Sarkeesian if she is okay. There is a demand for proof, followed by demand for the perpetrator’s name so they can bring him to justice, the implicit tone being that if she doesn’t “assist” the supporters, she’s still part of the problem. Never mind the fact that spreading child porn is flat-out illegal and demands police/FBI intervention; note the distinct divide here. The tone, specifically, was less “let’s work together and find this guy” and more “give us the name or is this yet another lie?!” Gamergate is many things, but primarily, it’s about controlling the conversation.

[An aside: how and why did harassment become some sick mark of honor? Instead of bonding together to stand up against harassment of all kinds, it seems that both Gamergate supporters and opponents are keen to prop up and point out their personal run-ins with harassers, as if to give them validity and their foes discredit. Again, aside from the fact that we’re really stretching the definition of harassment (there has to be relatively constant stream of attacks, or a threat against one’s well-being), this is an awful reaction to all of this, and doesn’t help either side.]

Then there’s #notallgamers – which, similar to #notallmen, and which gamers will insist, emphasizes that such examples of overwhelming harassment does not involve or include all gamers. The problem, again, is two-fold: 1) Of course such examples doesn’t refer to all gamers; not only is this known but its pretty much assumed by default (or it should be – again, this will be discussed later). 2) It is up to gamers to assume the role to directly confront harassers and be models of integrity against those harassers, not whine about the nature of being lumped into one terrifying stereotype. Believe me, I know: as a black guy, I completely understand the feeling of being part of a social group constantly misaligned because of a few bad apples. This is brand new to gamers, so they are struggling to handle this. My advice? Don’t play the victim, but be the light that shines on such vitriol and expose them. Don’t worry about the media never covering your more positive aspects. They never will. Just do good, and be positive about it.

Finally, there’s the question of exactly what gamers want with “journalism integrity”. This Vox article sums the entire thing up pretty thoroughly, and I would highly recommend this Medium article, because news journalism and games journalism do not occupy the same space, and there must be a general understanding of this fact before any type of real understanding can occur. Journalism in general is defined by writers building connections to expose real, in-depth truths about a subject; games journalism allows for more leeway in that fact because it is considered “enthusiast press,” not “news press.” Connections to game developers have always been part of the subject matter, even as game outlets indeed start to engage in real, investigative journalism, like Kotaku did at the very beginning of this piece. This is a fact. Ask any and all former and current editors of every gaming magazine/website ever. Add to this the fact that writers are relatively low-paid and are forced to find revenue through other means, including consulting gigs, it’s extremely important that gamers really understand the full nature of what it means to be a writer for an enthusiastic press before any real discussion over “corruption” can begin. (This Paste Magazine article is also a must-read; journalists are not a hive-mind of planners, but individual humans who err and function off subjectivity.)

There’s a lot here that gamers have to work through. Journalists, however, you are not off the hook.

IV. The problem with [game] journalism

I am on record as saying I actually do have a problem with the current thrust of game journalism, and even though there are many issues that gamers need to work through, I do think the core of Gamergate supporters’ concerns has validity. This is actually very reminiscent of the viewers vs. critics fallout behind Girls, in which both groups aggressively dug into the sand and refused to give ground on the criticisms lobbied at the HBO show. Prompted by this random gag pic of the show’s poster, Girls became an unfortunate symbol of nepotism, racism, feminism, and sexism in Hollywood. Viewers insisted the show represented the terrible state of representations in television today, and critics seemed to… dismiss it? That may not be the word, per se, but critics definitely downplayed these legit criticisms, which infuriated viewers. In the end, viewers actually won, with the slow but steady increase of broader, more racially inclusive shows coming around, and critics being a little more receptive of such socially conscious criticisms. Game journalists, I suggest you learn from your TV bedfellows.

This Badass Digest article makes a great example, in which the writer tries to define the typical gamer and how they think, and this doesn’t apply to me and not to gamers any more. The effort is sound, and there’s a “correctness” to it, but with gamers increasingly identifying as women, minority, and LGBT, such broad, generalized statements on what gamers are and how they think are no longer valid. This goes double for the awful, awful “Death of the Gamer” pieces out there, which does little to actually address gamers’ concerns. Gamers railing against “corruption” may be fairly nonsensical, but thought-process in evaluating the transforming audience is a real concern. These are people with concerns that you need to address, and they are tired of the basement-dwelling stereotype.

Game journalism has become less inclusive. I don’t think I’d use the word “corruption,” but there is the sense that game journalists have gotten egregiously caught up in the world of gaming – its glitz and glamor, its access and swag, and yes, even in the discussion of social justice without putting anything truly behind it. It feels surface-level. Reviews seem to toss out vague statements about the poor treatment of women and/or minorities in games without quite understanding why that treatment is so problematic (which is why I appreciate Sarkeesian’s work even if I don’t agree with all of it). Journalists are constantly fickle with their grading systems, the over-enthusiasm of AAA games seem oddly dismissal about such games’ serious short-comings, and the pick-and-choose nature of which indie games are worth looking into wildly random. And yes, perhaps there should be at least some sort of disclosure of which writers, at the individualistic level, are connected with which game companies or services. (Although I don’t think this is as big an issue as Gamergate supporters do, since, as mentioned, most gaming websites have such close connections with gaming companies and services by default.)

But the bigger issue is that wall that game journalists (and, to certain extent, most prominent bloggers and writers in general) have built in front of their fans, which prevents them from seeing the audience and the dialogue around games changing. Sites like Kotaku, IGN, and Destructoid feel increasingly loud and flashy, by design, gearing themselves for the young white (basement-dwelling) male, the very audience that they seem to be actively excluding now (without even bothering to be more inclusive of broader, more diverse audiences). These are sites with few female and minority staff members, sites that have had documented behind-the-scene issues with their staff that seem to go unaddressed.

In addition to some sort of disclosure about writer-to-company connection (which the Vox article does mention is happening), it may be in these sites’ best interest to cool it with the hostility and the “end of the world” declaration on the gaming public (and this Slate article explains why). It may be time for any and all references to that stereotype of “the gamer” as a young, fat, white, basement-dwelling nerdy virgin to be put to rest permanently. It might be time to start a real, close dialogue with the audience, assess games with a more critical eye, explore more investigative pieces, and open up the world of gaming to explore more outlier indie games. And please, for the love of god, stop whining about how hard you have to work while exploring venues like PAX, SDCC, or E3. I don’t think you quite grasp how off-putting that is, particularly in front of an audience that probably will never have a chance to attend.

Journalism can do better. And I will never say that journalists should stop tackling feminist readings of certain games, but we should discuss feminism for a bit first.

V. The problem with modern feminism [and most -isms of today]

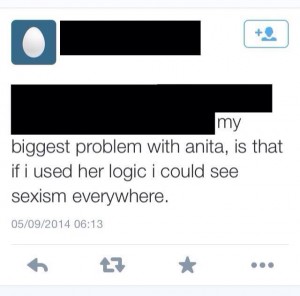

The above tweet fails to realize that, technically, that is Anita’s goal, and indeed the goal of most feminist readings. It’s not necessarily the point to “see sexism everywhere,” but to have, at least in the back of your mind, a more critical eye when looking at or experiencing media, to question how and why certain roles that women partake in are they way they are. The point of all cultural reviews is to prompt readers to cast a critical eye on the systematic use of coded tropes within the books we read, the movies/TV shows we watch, and the games we play; this is how art, and our culture, advances. There is a line, though.

“SJW,” or “Social Justice Warrior” is a tossed-around term that is usually used to rail against those who are deemed to be for censorship or political correctness via their one-track minded cause. “Social Justice” – and let us be very clear about this – is a good, good thing. SJWs, however, usually refer to the people who uses the cause to aggressively attack the status quo in uncomfortably ways, often missing (and flat-out refusing) any sense of context or inclusiveness. SJWs want a “thing,” and fail to understand how those “things” bring together or connect to other “things.” To SJWs, it’s do-or-die in a real-world war that is constantly trying to destroy the very cause the SJW is rallying for.

I am a feminist. I do worry that feminism is growing… exclusive, though. There have been examples of its dismissiveness of black women and LGBT issues, and there has been coded language tossed about that has implying the dangerousness of black males. Certain well-known feminist sites rally against people like Seth Macfarlane and Daniel Tosh, but then write what could be categorized as an “ironic” take on R. Kelly. Modern feminism also tends to downplay and even joke about subjects like prison rape, homosexual women, and transgendered females. I think its more aggressive advocates do approach SJW levels, absolutely dismissing any and all male assistance, and perhaps get too caught up in the idea of “speaking for all women”. Understand that I believe this only a small percentage of modern feminists, but I think that in the need to feel part of the collective, feminists won’t speak against one (or a few) of their own.

As a feminist, it’s my duty to speak up if and when feminism ignore real, black and/or LGBT feminist voices. (In fact, I did, when I wrote this long tirade against intersectionality). Feminism is a cause that I believe in, and I love that it has been gaining more traction and attention, but I’m very concerned that it is leaving its minority, LGBT, and its male supporters behind. It wouldn’t take much to tackle feminist’s intersectionality problem – more inclusive writers and more observations and analysis of black and minority females in various roles in media, whether in films, TV, or games, would help to open up the issue and give feminism a firmer footing to stand on.

—————————————————-

Given all these issues presented, even though I have my issues with game journalism, I think I tend to be on their side over the Gamergate supporters. I find their approach uncomfortable, engaging in a level of, if not hostility, then forwardness that seems more demanding than revolutionary. Like the Medium and Vox articles imply, it is not clear what exactly Gamergate supporters are aiming for (and I mean a very, very specific demand, as opposed to the nebulous “more accountability in game journalism” mission – how do you do that?). Being that every incident they’re railing against involves a woman’s involvement in games adds to the discomfort; perhaps if there was a male-only journalistic situation that raised eyebrows would I be more receptive to their cause. As it stands, though, it seems that while gamers, game journalists, and feminists have their issues to work through, it is gamers and the supporters of Gamergate that, at the very least, need a very specific goal, something that goes beyond the drive to remove Quinn, Sarkeesian, and Alexander from the field (since they managed to do this to so many other writers), and that goes beyond removing feminist critiques from game journalism, because I REFUSE that notion one hundred percent. I will not be swayed on this.

In either case, there’s a lot to be discussed here, and I’m ready to talk. Is everyone else ready to do the same?

Gargoyles “The Reckoning/Possession”

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Childhood Revisited, Television, Uncategorized, Writing on September 8, 2014

The World Tour has its critics, me among them, but by using the global journey structure, Gargoyles has been able to let individual and specific stories breathe on their own, such that when the gargoyles and Elisa returned home, there would indeed be a reckoning. “The Reckoning” and “Possession” are two great episodes that really tie the most important and “still up in the air” questions of the season. “Possession” has some minor flaws but overall is a pretty solid episode; it’s “The Reckoning” that is beyond reproach, by far the best episode of Gargoyles’ run. Barring the events of “Hunter’s Moon,” the three-part finale, Demona’s tragic and difficult life story ends here, in the most powerful way possible.

Gargoyles 2×48 – The Reckoning

Vezi mai multe video din animatie

“The Reckoning” cheats a little, teaming up Goliath, Brooklyn, and Angela at first, all three of whom has specific agendas against Demona, so of course they all find her first. It’s a fairly quick battle, but interesting to note that Brooklyn attacks first, the one character who hasn’t had the chance yet to work through his anger – and is punished for it. Goliath and Angela take Demona down within her battlesuit, and, in determining where to take Demona’s unconscious body, they figure the best place to send her is to the Labyrinth.

It’s all coming together now. The events after “Kingdom” has created an alliance among the Manhattan clan and the Mutates, and they come to an agreement to stand watch over the captive Demona every night for… I assume, ever. This I found absolutely fascinating. Gargoyles pride themselves – natch, live for – protection, for keeping a watching over the things they love. So with minimal hesitation, they agree to take shifts to watch one solitary figure, in a dark, dank room, all night, for eternity. They make it into a second job, they do this for over three months, and there’s nary a complaint. I can only imagine how tedious that must’ve been, but there’s a resolve to their task that’s undeniable.

Angela takes the first watch. Goliath tries to talk her out of it, but it’s Hudson who stops him. The show continues to establish Hudson’s wisdom in quiet, understated ways, and it’s always a treat. This leads to a one-on-one conversation between Angela and Demona, and it’s fantastic. Koko Animation, which handled expressions fairly well in the past, is pitch perfect here, nailing the expressions and framing needed to convey the pain, anguish, and sadness that Demona is feeling, and VO actress Marina Sirtis is on point with every line read. It’s depressing, to see Demona, for a brief moment, express what might be happiness at seeing her daughter, only to jump right back into her rage when Angela tells her about Katherine and her protection of the eggs. Stark proof right there that humans can be helpful, saving her own daughter, but Demona can’t accept it. She won’t accept it.

All this time, however, Demona has been secretly sending out mechanical bugs to suck the blood out of various Gargoyles’ characters. I was a little reluctant about another sci-fi plot – mainly because the conversation stuff between Demona and the various members of the clan was so, so good – but this led to some unexpected developments; namely, the bugs being sent back to a Nightstone Unlimited, where Dr. Sevarius is using the DNA to construct… something, for a well-paying Thailog! Giant genetic “things” in a vat can only mean clones, and Thailog is raising them to be brutish but loyal. Thailog, voiced by a sassier version of Keith David, is just fantastic, as always, and Thailog is really just having fun as the tensions mount.

After a few months, the shit hits the fan. Thailog crashes into the Labyrinth and frees Demona, and the two reunite in love… per se, since Demona still isn’t aware of Thailog’s attempt at his betrayal way back in “Sanctuary,” so we’re witnessing yet another layer to her tragedy. The two escape, freeing Fang in the process, who was there, captured as well, making lame quips and being a nuisance, but it’s okay, since he’s much better as a side villain than the main antagonist of an episode. Goliath and Derek chase them down to an abandoned theme park – a classic showdown location, so kudos, Gargoyles. Goliath gathers the crew, and it’s about to go down.

It’s Thailog who has the jump on them, though. Unleashing his creepy clones onto the unsuspecting crew, the Manhattan clan and Derek are ambushed by multiple doppelgangers and held captive. Thailog is so great, only he can get away with classic evil monologuing, as he regales everyone his massive clone plan and the necessity to keep them stupid. What I like about this part, though, is Thailog very subtly and very carefully decides to try and kill Angela first, mainly to test Demona’s loyalty. Demona has little left to fight for, and while Thailog makes an ideal Goliath substitute, Angela is her actual daughter. She tried to turn her, but failed. Demona has been driven by hate all these years, but when Angela tells her mother point blank, “I hate you,” there’s a moment, a small moment, where Demona realizes she lost her, and all of this was for naught. Yet even in that moment, she still prevents Thailog from killing her.

Then Thailog reveals his most secretive prize: a clone of Demona mixing her DNA with Elisa’s, as an added “fuck you,” because Thailog, yo. If Demona’s lowest point was Angela’s hatred of her, than this is a figurative “kick ’em while their down” moment. This hybrid, called Delilah, adds an extra brand of creepiness to the proceedings, by being a female that only he can control. Thailog can control the clone gargoyles, yes, but they’re kept stupid, more or less just flesh robots. Delilah is something else, the pure representation of male control, both blindly loyal and a literal-created sex object. Plus, she’s a creation of everything Demona has lived for (herself) and everything she loathed (Elisa and her humanity). When Demona finally fights for something other than herself, it feels wonderfully, powerfully redemptive. “Goliath, save our daughter!” she bellows before freeing them, and the line-read is so perfect I am near tears.

This leads to the most badass battle this show has ever done. Koko gives the A-Team a run for their money, simply by keeping the three fights in clear and distinct contrasts: Demona/Goliath vs. Thailog, the Manhattan clan vs. the clones, and Talon vs. Fang (there’s also a Delilah vs. Angela conflict, but we never see it, and Delilah never stood a chance). It’s an intense fight, not because of the dynamic staging against the backdrop of the slowly destroyed carnival, but also due to the unique contrasts in battle. The Manhattan clan realize that key moments of collaboration are the best ways to take out the single-mindedness of the clone. Talon takes down Fang, mainly because Fang’s a shitty fighter. And Demona is just going all out on her final fight for vengeance, and she and Thailog go at it, even as the fires of the roller coaster burn all around them. Goliath tries to save her, but is force to flee before the burning wood collapses all around them, leaving Demona and Thailog to disappear among the ruins. “Do you wish to perish?” Thailog asks, with a bit of a whimper to his voice. “My vengeance is all you left me,” responds Demona responds, without a hint of irony: vengeance is all Demona ever had.

It ends with a bunch of lost clones needing a purpose, which Derek will provide (along with proper verb usage). It is purpose, though, that led to this tragic moment, that brought Demona down a road of pure hatred, only to have her first “goodness” in a long, long time. Whether she’s dead or not is a moot point; Demona has found redemption, a new beginning, even if that new beginning was but for a few minutes. Angela may have told her he hated her, but maybe Demona saw in that statement, in that moment, a true reflection of herself (signaled by Angela’s glowing red eyes), prompting a change that signaled a need to fight for something beyond avenging gargoyles. Demona, you lived a tough life, and while you never found peace, you’ve at least found a purpose.

[She’s probably not dead. She’s still cursed and connected to Macbeth. Still, the episode plays it so, so well.]

Gargoyles 2×49 – Possession

Vezi mai multe video din animatie

“Possession” is a solid episode too, although it gets a little cluttered in the middle. It kind of feels like it’s reveling in its cleverness, but it’s not letting the audience feel clever along with them. It also doesn’t help that it involves Coldstone’s internal brain demons, which has always been an Achilles’ heel of the show, since those brain demons feel woefully underdeveloped. Two of them are in love. One of them is evil. The ultimate goal is clear.

Gargoyles never quite had a handle on the cyberspace elements, but that was just a general interpretation of cyberspace that existed in the 90s, and the show did the best it could with that interpretation, creating an interesting dynamic battling inside Coldstone’s head. It’s a fight for Coldstone’s soul essentially, which is one of the many secondary themes of the show – struggles for some sense of control and/or independence. Coldstone left the Manhattan clan to try and win his internal battle, but Xanatos seems to have other ideas, after his robot gargoyles subdue him in the midst of the Himalayas and drag the cyborg gargoyle back home.

I like that Xanatos is still naturally a sleezeball. Even with his intentions noble and pure, he never actually tells Coldstone he’s helping him, nor asks for his consent. He just fucking does it, or at least tries to, until it’s clear that science alone won’t purge Coldstone of his conflicting personalities. He then just leaves Coldstone’s head all separated from his body, because that’s the kind of guy he is. Gargoyles’s message is clear. People don’t change, even if their goals do.

It’s all a little disappointing. The second that Oberon told Puck that he could only use magic when training Xanatos’ son, it’s clear that Puck/Owen would be using a training session with Alexander as a means to do some trickster magic. Of course, the episode does a good job of understanding that a training session with Puck would still be confusing and full of tricks and misdirections. I guess magical beings don’t change much either, and what follows is a mindfuck of body transferences and high-level pretense.

Recapping the plot in detail would be a bit out of hand here, due to the sheer amount of body-swaps that take place. The gist is that Puck and Alexander first pretend to be Goliath and Hudson, and they use magic to draw out Coldstone’s three personalities into Angela, Broadway, and Brooklyn. The fun part is that the writers, who always viewed Gargoyles as a heightened take on Shakespeare, takes the allegory up to eleven, with the three of them talking in amazingly delicious hyper-Shakespeare-esqu dialogue. The three voice actors of Jeff Bennett, Bill Fagerbakke, and Brigitte Bako just have fun with their ham-chewing lines, with Brooklyn playing the plotting, cantankerous villain, and Angela/Broadway as the tragic lovers. If anything, just watching the three of them do Shakespeare in the Park is just loads of fun.

Not to say there isn’t a worthy amount of tragedy here. The episode is definitely committed to its characters, so there’s a real concern on whether these souls will willingly stay trapped in the stolen bodies. Even the wholesome duo of Coldstone/his lover discuss this, in their desperation to physically feel each other again (and the sexual tension is not lost on this episode), which creates some scary overtones. Cooler heads do prevail, particularly once Puck-as-Coldstone introduce Coldsteel and Coldfire as potential conduits. The demon in Brooklyn sees Coldsteel in action and wants a piece of that, which Puck grants, and the figures inside Broadway and Angela acknowledge their fate, to which Alexander-as-Lexington (don’t ask) grants by sending them into Coldstone and Coldfire respectively. Everyone is back to normal, Xanatos gets his noble wish granted, and Alexander gets his first lesson, courtesy of Puck’s Rube Goldberg Method of Teaching.

It’s a solid episode, if a bit messy when the head games really begin, but it’s all done on purpose, a confusing episode meant to make all sense in the end. Still, while the character misunderstanding is fine, a bit of plot/pacing clarity would’ve worked in the episode’s favor. It’s no matter, though: the last four episodes have been fantastic overall, and with the season finale of Hunter’s Moon next, we’re looking at a fantastic endgame to an amazing show.

“The Reckoning” A/”Possession” B+

CHILDHOOD REVISITED – Road Rovers

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Childhood Revisited, Television, Writing on September 4, 2014

Road Rovers’s lofty premise failed to commit to anything of substance to sustain into a cohesive whole. The question is, why?

I have seen a lot of cartoons by this point. I have seen the good, the bad, the ugly, the beautiful, the strange, the weird, the bizarre, the outlandish. I’ve seen action cartoons, wacky cartoons, subversive cartoons, serious cartoons, and surreal cartoons. I’ve geared myself to engage in every type of animation out there, whether for kids or adults, cracking my knuckles and prepping my fingers to explore what happens within the animated frame and how those events could affect viewers, and how over time those effects may be viewed in a modern context, or within any context at all.

Then there’s Road Rovers, a show that seems so stifled that it’s almost impossible to engage in. Almost.

Road Rovers is a curio. I kind of feel like Homer Simpson when he described what a Muppet is – that is, if you were to ask me what Road Rovers is about, I would respond: “Well, it’s not quite an action show and it’s not quite a funny show, but man… so, to answer your question, I don’t know.” Honestly. I’m not exactly clear on what the Road Rovers was aiming for. For a show spearheaded by Tom Ruegger and Paul Rudd, the geniuses behind Tiny Toons, Animaniacs and Freakazoid – three shows with enough narrative oddness to compete with the Bible – Road Rovers may be the oddest of them all, because it seems reluctant to commit to its oddness. Or anything at all, really.

Road Rovers takes its cues from the Power Rangers, and other super sentai shows that were popular (and still are, to a certain extent), in which five or six plucky characters are chosen to be a super-powered fighting force battling evil where ever it may be. Instead of humans, though, the show opts for dogs, which allows it to dip its toe into the early 90s badass, macho talking animal action-cartoon template as well. Road Rovers is clearly building off these two concepts and attempts to, more or less, undercut those ideas and ridiculousness of them.

Yet Road Rovers doesn’t exactly build into anything on its own. It doesn’t really even undercut the super sentai show or the talking animal action cartoon either. The show kinda plays into those elements with this weird, lackadaisical malaise, lightly elbowing and jabbing at all these elements – the action, the comedy, the story, the commentary, the metacommentary – without strongly committing to any of it, or even to the very premise of the show itself.

A lot of that probably sounded like gobbledygook. Let’s look at the pilot, “Let’s Hit the Road.”

Road Rovers Episode 1 “Let’s hit the Road” by dm_51e63c6f9122b

The first five minutes are played completely straight. It’s a bit slow (which isn’t necessarily a problem, but there’s a sense that it’s padding for time), and considering it involves a scientist being blown up, there’s a sense that viewers should be taking things seriously. Then the dogs are summoned. It’s a silly scene, but it’s portrayed with a quiet wonderment, and for a while it’s unclear whether it’s supposed to be funny or awe-inspiring. The first “joke” involves Shaggy, who’s whimpering in fear of his summons. We’re treated to Hunter, who saves his doomed doggy pal before he’s called upon, which gives us a direct indication that he’ll be the leader. Then they’re all transformed into their anthropomorphic, metal-suited selves, and present themselves before their “master”.

A few quips aside, everything is portrayed as direct and sincerely as possible. But that can’t be right, right? The machine that transformed them is called “the transdogmafier,” and it’s a phrase that is spoken by an actual person, and it’s not supposed to elicit chuckles? Then when the master tells the dogs to greet each other, it’s done via an off-camera gag with the Rovers’ tails in the air, indicating that their sniffing each others’ butts. The master sighs and laments he should’ve used cats. It’s a cute, easy gag, but I’m not sure how to take it considering we’re nine minutes into the show. It’s a gag that pushes it into the ridiculous realm, but the show doesn’t feel ridiculous enough to pull it off.

That’s just it. It’s hard to gauge how to respond to the show. In the middle of various action and dramatic scenes, characters will sort of shoot out these really casual comedy bits that seem tonally off. I get the sense that the creators were aiming for a “casual action cartoon,” something where the characters amicably shoot the shit with each other while things blow up around them, a thing that happens quite often with the Rovers themselves. It’s an admirable attempt, but the result rarely creates a solid comedy, and it drastically lowers the action/dramatic stakes. It creates a show that feels perfunctory at best, and ill-thought out at worse.

“Let’s Hit the Road” is actually part one of a three part series (along with “Dawn of the Groomer” and “Reigning Cats and Dogs” [I think – the episodes weren’t aired in any order that made sense]) that gets into the nitty-gritty of the master, Professor Shepherd, the villain General Parvo, and The Groomer (Parvo’s assistant and potential lover), and the origins of this transdogmafier. That is, there is a mythology. The show is dedicated to that mythology, but it’s inherently silly, and the show knows it is, but it’s an attitude that doesn’t adequately show up on screen. Plus, it’s a mythology that doesn’t hold up to even mild scrutiny, particularly when they start bringing in Egyptian spells and time-travel. It’s needlessly complicated, which again, would be fine if the show had fun with it. But it treats everything with this weird heavy weight, making it more off-putting then it needs to be.

Yet as mentioned before, the show feels like the joke is in placing its characters in tense situations, creating like a “hangout” show in the midst of an action show. Unfortunately the characters don’t have strong enough personalities to stand out individually, let along make a compelling exchange. Hunter is just a really positive guy. There’s nothing much going on with him other than his optimistic response to everything, but it’s always level-headed, not heavily exaggerated like a Spongebob or a Wander. Colleen is fine but kinda fits the “bad ass female” role, regulated mostly to quipping with Hunter and Blitz. Blitz is the comic relief, although he doesn’t really work. He freaks out at the sign of danger – but so does Shaggy, which defeats the purpose (Blitz and Colleen have a running gag where Colleen pretends not to know Blitz when he hits on her. This doesn’t work because 1) the sexism is too strong here, 2) Blitz is too stupid to vary the responses to this gag, and 3) Blitz works better as a goofy but functional member of the team.) Exile seems to be the writers’ favorite, with his relatively witty putdowns and depth of character that’s lacking with the others. His running gag – reading simplistic children stories in the middle of missions – work the best, because it’s fits his character AND it’s patently absurd.

Lacking a strong premise and a strong cast, Road Rovers kinda limps by with a non-committal attitude that makes it hard to really get behind. Still, the show has promise. The best episodes work with its undeveloped premise, inserts a simple story, and lets it loose. “Where Rovers Dare” is epitome of this. A scepter has been stolen and the Rovers have to get it back. It’s a simple, straight-forward action episode, not bogged down by too much information. It’s enjoyable to see the Rovers in their element, and their banter doesn’t pull too much away from the plot. (“Where Rovers Dare” also has a smartass allegory in its premise, written by this person on Deviantart and confirmed by Tom Ruegger himself. Problem is, the show isn’t overall an indictment of studio cattiness, so don’t expect to be looking for hidden messages everywhere.)

Once the show tries to be complex, though, it fails. The show is too silly to insert that kind of complexity because it raises too many questions the show is not adept at answering (like its mythology), and the obvious lack of a budget and quality writers makes it hard to look good. “Still a Few Bugs in the System” is just a disaster, introducing a bug-crazed scientist who seems like a caricature out of a wackier cartoon. But the episode is sloppy, with nonsensical storyboards and an even stupider plot. “Gold and Retrievers” has a blind kid who’s a native, but also seems to be a leader of a tribe, but it’s never made clear, and it’s frustrating (the show has an obsession with pyramids but nothing is ever done with it, narratively or thematically). “A Hair of the Dog that Bit You” brings in other talking anthropomorphic dogs, characters we never see again, and it’s a baffling reveal. We’re these dogs made by the transdogmafier too? Why is one sitting on a mountain, Dali Lama-style? The show isn’t wacky enough to get away with these kinds of absurd reveals; it’s unclear whether to insert them into the show’s mythology or place them as a comedic outlier. The other episodes are okay, with “The Dog Who Knew Too Much” containing a clever twist, but again, the show doesn’t engage with either its serious or comic sides, making it hard to support it.

A friend of mine is a fan of the show and spoken with a few of the writers/animators in light of the show’s fallout. They basically were working with less of the resources they had with Animaniacs, and it shows. Hunter’s eyes are different colors for several episodes, and Blitz sometimes will have Hunter’s fur colors. They recycle animation and scenes constantly; a post-Muzzle attack re-uses the same exactly shot and background, despite Muzzle being in two different locations in two different episodes. (An aside: the Muzzle-kills-everyone stuff fails to work because the audience doesn’t even get a sliver of an indication that Muzzle’s attacks are grotesque. Also, if he’s so effective, why not unleash him all the time?) I sympathize with the lack of resources, but the team behind this show is way too talented to let monetary concerns limit them.

Road Rovers 13 – A Day In The Life (Unedited… by extremlymsync

“A Day in the Life” seems to be the kind of episode Road Rovers was always going for, which suggests the show needed a gimmick or absurd frame story to situate its characters inside, so that its seriousness and its silliness can breathe in its own way. The title cards indicating the changing timeframes allow certain moments for the characters to hangout and chat, and other moments for them to kick ass. Hunter’s search for his mother is effective, as well as Colleen’s feelings for him are explored, which allows her to actually talk with Blitz in a mature manner. Exile works as a team communicator, and the little comic bits they come up with are, if not funny, enjoyable that deepens the characters instead of forcing dialogue gags to disrupt the momentum (the edited “Russian name bit” is too much – not because it’s offensive, but because it’s really just an Animaniacs gag forced into Road Rovers for no reason).

That bit is Road Rovers in a nutshell. Unable to commit to its drama, action, or comedy, the show tries to do all three but ends up doing neither. The passion is there. You can feel it pushing against the edges of the show. But as the cliche go, Road Rovers’ bark is worse than its bite.