Posts Tagged Writing

Star Vs. The Forces of Weirdness

Posted by Admin in Animation, Television, Uncategorized, Writing on July 6, 2017

There’s an episode in the second season of Star Vs. The Forces of Evil called “Trickstar.” Weird Al Yankovic voices a creepy magician named Preston Change-O, who is invited to the birthday party of Marco’s sensei (at this point in the series, Marco and his sensei are friends for some reason. I’ll get into this in a bit.) Star, she of the magical propensity from the alternate world of Mewni, vaguely recognizes Preston and begins to suspect that something is off about him. Indeed, when Preston performs a magic trick, and his audience cheers, Preston sucks up the energy from their enthusiasm. He literally sucks in their “joy,” and his hat grows longer. It’s kind of a ridiculous visual. Anyway, Star recognizes this danger and tries to warn everyone, but those around her deem her a spoilsport – someone who’s trying to steal all the attention from the sensei’s festivities. Ironically, the episode does purport that Preston’s joy-stealing is, at worst, just a small annoyance: no one is deeply affected when their joy is snatched, and Star’s obsession does make her seem overzealous (the episode never quite expounds on what exactly this “joy” is, undercutting the plot; I’ll get into that deconstruction later). Well, no one is affected but Jeremy, whose joy seems like it’s completely gone, and is left sitting on the sidewalk as an ultra-depressed husk. The show posits Jeremy as kind of a joyless loser, but not the kind whose captured happiness seems warranted. Jeremy is all but rendered useless, but other than that “Trickstar” tries to be clever and undercut a common animation plot trope (with… another plot trope?). It doesn’t quite work.

Star Vs. The Forces of Evil has had a hell of a second season. The first one was a fun, wacky romp of adventures and insanity, with a John K. sensibility that overcame the weaknesses of some of the characterizations (most notably in Marco’s friends, who are rarely seen in the second season). The show’s sophomore run toned down the abject silliness a lot, opting for something a vibe that is split between Steven Universe and Adventure Time; the aesthetics are more grounded, measured, and methodical. It’s a pretty notable shift, and it’s a shift that’s not just regulated to the animation. The characters are more… well, I don’t want to say mature, but they are more distinct, more complex in a way that suggests the writers are pursuing long term development for its cast. What makes that stand out, however, is in order to do that, Star Vs. has decided to travel down some insanely odd, unusual, unconventional narrative paths to get there.

I think about that “Trickstar” episode a lot; it’s such a good example of what the show seems to be trying to do, and yet, stumbles on at times. I think the idea of subverting the narrative trope of a figure who sucks some kind of “essence” from people is worthy of doing, but I question the end result when, essentially, one character is effectively destroyed by it, and the weird, tonally off, ambivalent/ambiguous/indifferent theme of the entire episode (let’s be clear: Preston is stealing something from people, and whether or not it’s “harmless” is besides the point – it never was his to take). Star Vs. is clearly eager to subvert and/or deconstruct the kinds of episodes we have come to expect in our animated series. I don’t think it does a great job; or, more accurately, I don’t think it has quite a handle on the full extent on the narratives it tries to subvert or deconstruct (certainly not to the extent that Gumball does, which understand its tropes in minute detail so that its subversions/deconstructions work beautifully).

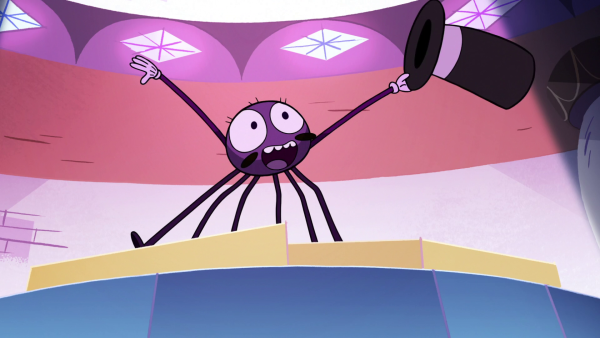

Take “Spider with a Top Hat,” a wildly off-beat episode in which we explore the lives of the very strange, whimsical animals that zap forth from Star’s wand. The creatures spend their lives within Star’s wand like a TARDIS, prepping their existence in order to do battle when summoned; a hapless, cheerful spider at the center plays the role of moral support for these magical warriors. The spider is also pining for his chance to be summoned into battle as well, even though he can barely break a wall with his head. This…. all works better in context, its baffling premise making more sense on the animated screen. It’s a narrative that’s certainly unexpected, but waddles into laziness when the spider, upon being summoned in desperation during a viciously tense battle, suddenly deploys a gattling gun from underneath his top hat. It’s a sudden, throwaway climax to a unique story with a unique premise: the kind of answer you’d find in a notebook of a eight grade boy. “He had a BADASS gun inside him all along” is flat storytelling.

That’s the kind of episode development that hints at Star Vs.’s core issue. It’s second season truly seeks to tell very unique, very audacious stories, but in many ways struggle to push that desire into something meaningful or perceptive. All of the crazy, wild narrative beats and questionable characters are put in place to throw audience expectations askew, but it’s clear that’s just all the writers want to do. The main thematic thrust is about insecurity, mainly centered around a jealousy Star develops when Marco and Jackie (a typical bland, “chill” female character) begin a relationship. Insecurity is part of most, if not all, the episodes of the season, and you can make the raw argument that these off-kilter storylines are meant to instill a level of discomfort and awkwardness in the viewers as well – you’re supposed to feel uncomfortable from the “incompleteness” of an episode, to best reflect the uncomfortableness felt buy all the characters, their relationships, and what they’re all going through.

It’s extremely tough for me to buy, though, as some of the decisions feel less like a bid for thematic resonance, or connections towards insecurity and discomfort, and more just narrative curveballs for the sake of them – both in characterizations and it storytelling choices. For example, Star Vs. opted to lean on an assortment of new characters defined by a “quirk” that’s less “pixie” and more “disturbing”. The first episode introduces a women who collects hair; when she admits this, there’s a music cue that indicates danger. But she’s anything but: she in fact helps Star through her predicament. Which is fine, within the broad, generic lesson of not judging books by their covers. The overall impact of her appearance is moot, though: other than a reference to this woman and her weird hobby later in the season, she feels like a waste of a unique character. Other weird characters include a dog suffering with depression, a insecure being with talking snakes for arms (who gets in way over his head), and a former Mewni warrior turned homeless-sociopath on Earth. Each character is unmistakably distinct, but they never leave a lasting impression. What purpose do they serve, particularly in a season clearly working its way towards a bigger, grander arc? Even recurring characters feel formless. I somewhat can abide by Tom and his anger issues, but he functions better as a toxic, masculine obstacle to Star than jerky man-friend to Marco. I can’t say the same for Marco’s sensei, whose friendship makes less sense than Marco’s original first season friends – at least they were in the same grade as him. Marco’s sensei is a pathetic manbaby who more or less guilts Marco into befriending him, which in and of itself is a pretty toxic event.

And sometimes, I think the show misunderstands the difference between insecurity and personal secrets. “Naysayer” involves a curse that’s supposed to get Marco to admit his deepest secrets, but the episode ties them to his insecurity, and fails to realize they’re completely different. Nervousness in asking a girl out – and the hundreds of reasons that one conjures up that would prevent said girl from returning the affection – is the key to Marco’s insecurity. “Naysayer” forces Marco to just say a bunch of weird personal stuff that he does. I get that the show is trying to tie those personal behaviors to his fear of asking Jackie out, but since we’re not clear on what specifically about himself and those behaviors that worries him in relation to Jackie, it comes off completely the opposite of what the scene probably intended. (You try telling someone you barely know all the weird shit that you do out of the blue.) But since Jackie is barely a character, she’s totally cool with it all.

This is, in some ways, a manifestation of an issue that bogged down the first season: Marco receives quite a bit of screen time for a show ostensibly titled Star Vs. the Forces of Evil. And it’s not as if Marco is a bad character. He’s clearly an important one as well. But Star’s conflict, whose personal sensibilities and attitudes butt up against Mewni’s expectations and historical legacies, is a juicier, meatier narrative than anything to do with Marco. While I admire the second season’s attempt to blend her conflict with the emotional struggle Star is going through upon learning of Marco and Jackie’s romance, it still remains at odds. It feels like a narrative step back from the lesson she learned in “Sleepover,” where crushes and desires ebb and flow overtime, but it also feels like a secondary conflict forced to the surface over the more intriguing narrative of the bizarre Mewni situation involved Ludo, Bullfrog, the return of Toffee, Glosseryk, and Star’s own mother. Also, to be blunt, the narrative building of this conflict comes off incomplete, a smorgasbord of mediocre, world-building, wheel-spinning that, to me, signifies a backstory that’s still being worked on. Nothing that occurred this season seems meaningful, important, or intriguing enough to follow. The reveal in first season’s “Mewnipendence Day” – that Mewni was most likely the aggressive force that subsumed the more innocent, native monsters – feels more worthwhile than the vague information that dripped out during the course of the season.

Looking back over that second season, eyeing episode descriptions while re-watching select ones, I admit that despite my criticisms, my curiosity is still piqued. Yet it’s not for a real desire to learn the secrets and truths of the world and history of this Mewni/Earth setting (and the characters that inhabit it), but more for the sake of relief – an assurance that the creative team does, in fact, have a real long-term arc ahead of them. I’ll swallow up Star’s personal feelings and heartache if that struggle is dealt with in strong collaboration with the greater conflicts and reveals that will emerge from what Ludo, Toffee, Glosseryk, and the entire Butterfly family holds. What do we know at this point, in terms of the overall story? We learn that Star is extremely powerful, which would have been better served to learn as we see Star’s power grow (we don’t really see this). We learn someone is “draining all the magic” in “Page Turner,” which is just a nebulous statement – why should be concerned about this? And by the season finale, we learn that Toffee is back, which is cool (Toffee was one of season one’s greatest characters), but we don’t know what this means.

And yet, I don’t think that the second season of Star Vs. is bad, per se. A lot of it is great, and interesting, and just weird enough to keep paying attention to, and it’s worth at the very least talking about, way more than any potential Marco/Star ships. I do think that, in its desire to be part of the pantheon of great cartoons like Gravity Falls, Gumball, Adventure Time, and Steven Universe, it sought depth and irony and deconstruction and subversions, but it all amounts to blank slates and purposely confusing oddities; its weirdness is the animated version of what Matthew Christman describes as (animated) TV becoming respectable without getting better. For all it’s faults, I do respect the hell out of Star Vs. The Forces of Evil, and maybe its third season premiere will tie this all together in some significant way. But it’s desire to be a game-changer makes the entire season seem like work: I can feel the effort and strain behind it to be “talked about.” What I don’t feel is the one thing that Star herself would want to be: fun.

Warner Brothers’ Storks Film Carries More Weight Than Just Babies

Posted by Admin in Animation, Film, Uncategorized, Writing on June 14, 2017

Storks received some minor attention when a Twitter account pointed out a montage from the film showcasing various couples – and singles – receiving babies from the flying avians. The recipients were of various races, ages, sizes, and sexuality. It was a slight scene, and it was really only for those who would take notice, but it still was worthy of attention. Storks seems like it’s part of the not-so-great trend of films playing minor favors towards progressive ideals – a sentiment that feels more like a “spot the trend” game than any real sense of modern acceptance of diversity. Storks, a movie as a whole though, is genuinely more interested in those progressive ideals than a tossed-off montage. Storks is generally dismissed as a non-essential children’s film. But it’s a funny, clever, self-aware bit of animated goofiness with its heart firmly held in its silent, but meaningful, progressivism.

Storks, at the onset, feels like its a film about nothing, really. It’s the off-beat, quirky story of a stork at a company, which no longer delivers babies, teaming up with a orphan human girl, to do just that. The movie runs through an assortment of wacky set-pieces and silly characters via a plot that on its surface is rather simplistic and superficial. Its reliance on heavy cartoony antics and self-aware gags can be a turn-off to a lot of people who prefer their animated films to be more grounded and sophisticated (an approach I find limiting in a lot of ways but that’s a topic for another day). Yet underlining all of that silliness, Storks exhibits a real sense of confidence in its characters and in its setting – a confidence that is exploratory and distinctive, noticeable with a closer look.

I hate saying this, and I hate how this will sound, but I need to say this only in order to clarify it: Storks is arguably the most “millennial” movie I’ve seen in a while. It’s a film in which its absurdity and irony attempts to, but doesn’t quite, mask its dramatic exploration of the confusion of life and complications that younger “20-somethings” face. It’s a film that comically but quietly explores their contemporary search for purpose and identity – in a wildly basic way, but in a way that feels necessary. Storks wears its heart on its sleeve. It is quietly, narrowly honest, but that honesty is cluttered in self-awareness, funny voices, and physical comedy – the kind of way in which millennials tend to approach their futures.

It’s tricky, almost dangerous, to explain myself without stereotyping, but hey, I certainly wouldn’t be the first critic to speculate on “what millennials are” these days. In my experience, I find that this particular upcoming generation is more honest and forward than the previous one, but often diffuses that honesty through irony, asides, and forced comedy. (You know, memes.) Storks isn’t a “meme” movie, in that it didn’t inspire an array of JPEGS and GIFs tossed about on social media, but its core sentiment is easily lost in its nonsense. One could suggest that the film’s failing is exactly that – its sentiment is belittled by its chaotic cartooniness. But I feel like that’s a shallow reading of cartoon antics in general, an implicit denial of letting cartoons be cartoons. That is to say, all of those antics don’t deny the film’s sentiment, even if the characters aren’t the utterly raw, broken characters, like the ones in Bojack Horseman or Rick and Morty. The cast of Storks are lost in deeply confused, deeply aimless ways, composed of characters who are coded in youthful exuberance and confidence but not necessarily a purpose: Junior the stork (note the name) is up for promotion without any idea as to what to do when he gets it, while Tulip the human is a literal 18 year-old orphan who has no idea who she is or where she belongs.

Storks is somewhat atypical of most animated movies in that it places much of its stock on those two characters for a good portion of its runtime. All the physical gags and loose plotting is secondary to the film’s confidence in the interplay between Tulip and Junior, and essentially the voice artists Katie Crown and Andy Samberg. And it is a delightful pairing. Crown and Samberg work off each other so well that it almost feels like certain scenes were added and/or extended just to pad their interaction. Their comic conflicts and camaraderie move fast and sharply, due to the power of two actors on top of their game. Yet even through those comic interactions, Samberg and Crown don’t deny or ignore the complication of their characters in this weird, specific moment in their lives; they instead manage to exude their current turmoil through their hilarious performances. It’s not nuanced, but millennials aren’t particularly nuanced (and I mean this positively). Just because someone posts a meme that dumbly describes their current feelings doesn’t negate the fact that they’re indeed feeling that feeling.

It’s immediately present early in the film, when Tulip gleefully asks Junior to stop calling her “orphan Tulip”; she comically, but bluntly, describe how the term “hurts her heart.” Later in the film, Tulip teases Junior over his ideas on what he would do once he’s promoted. After a bit of inane, silly prodding and subsequent deflections, Junior reacts in anger: “BACK OFF” he screams. It’s a hilarious but personal response to his dilemma – what does he truly believe in? What is his personal drive upon “earning” his position, and what will he do when he achieves it? Junior is terrified of self-reflection; throughout the film, he blindly recites the corporate slogan, he sings the commercial jingle to a baby, and he grows excited over Storkcon, a convention in which its cleverest innovation is a spherical box.

I don’t think millennials aren’t especially hostile to capitalism, so much that they’re more readily and willing to question and criticize it. “Climbing the ladder” is still the goal of many young people, but as it becomes clear that such an achievement is more complex and fraught these days (financially, socially, and mentally), millennials at the very least need a real sense of purpose within the system that goes beyond “it’s just what you do.” Junior’s mind literally explodes when he gets that promotion early in the movie, yet the story showcases his reluctance to articulate what, exactly, he would want to do once he achieves this. Tulip’s assured ideas push back against Junior’s smarmy question over what she would do in his position, but it also reinforces how specifically lost Junior is in this particular point in his life.

Speaking of Tulip: I just have to say that the Storks’ co-lead is a fantastic character. She pulsates with such life and personality, a funny and quirky being who also shades a lot of complexity in her actions and her vocal performances – and in her animation. Tulip is a brilliant young girl who never is given her due: she invented (and fixed) a flying machine that doubled as a boat after a plane crash, and her rocket packs actually work before one of her test subjects take things too far. (You then want to question whether “Tulip’s help” really was the cause of the company’s low profit margins.) Let’s be blunt: there’s a clear, prescient feminist message here. A smart, capable woman whose ideas are dismissed, who can’t even be seen as a real person without the “orphan” qualifier? Really, there’s enough here that could fit an essay on its own. (This also ties into capitalism’s problematic approach within a social context, but again, that’s worthy of its own, separate critique.)

What we get here, through the overall tale told in Storks, is two young persons of different lives (and species, which winks towards its own idea of a diverse co-lead setup) who struggle with modern ideas of personhood and livelihood, all while engaging with the ultimate symbol of the classic “success” traditional ideal: the baby. And here is where things get interesting. Junior and Tulip fit within a particular archetype. A young couple, both of different worlds, who find themselves suddenly in the care of a child, neither of them ready to care of it, let alone care for themselves. They’re literally figuring it out all their own. In this way, Storks attempts to bridge traditional ideas of social success while questioning it all the same.

And, to be very clear, Storks isn’t a movie that’s going to delve heavily in such an idea. It’s silly, audaciously funny, with the kind of animated physicality that rivals Tex Avery for delightfully dumb cartoon exaggeration. The last CGI film to do something of this caliber is probably Madagascar 3 (one of mistakes of the Penguins of Madagascar movie was arguably to pull back from that gleeful embrace of cartoon exaggeration). Storks delights in its visual nonsense: its bird characters with hilariously perfect teeth; it’s fun, revealing montage of Tulip’s cast of imaginary workplace characters; it’s most sharpest creation in the form of a male wolf couple (wink) who fall in love with the baby and commands its pack into sheer physical recreations of bridges, mini vans, and submarines.

But those exaggerations do not (and should not) distract from its richer, well-considered points; they reflect millennial confusion and fears over how to approach a society that continually questions the nature of livelihood and family. Storks feels like a movie in which its creators almost lucked into devising a smartly considered world and a thematic heft that balances the film more than its previews indicated (and which hinders its third act a lot, which I’ll get to in a bit). In Tulip’s brief idea, suggesting the company they work for invest in a more diverse set of birds and animals, Storks sparkles with potential of a world in which its animals have as much life as its humans. It’s present in the wolves and the throwaway scene in which Toady interviews a bunch of animals. Storks enjoys the world it created and meta-commentary that flows from it.

This, in some ways, is also reflected in the scenes involving Nate Gardner and his family. Here, tradition again is questioned, if perhaps not as rigorously as it is with Tulip and Junior. It’s as cliche as it comes when we see two overworked parents consistently neglect their own kid, but at the very least, Nate thrives with a clear self-awareness of the situation, as in with the scene where he guilts his father to help him built the baby-catching contraptions on his house. Storks smartly doesn’t dismiss out of hand traditional ideas of success and family; it simply requests that its characters understand why it wants to achieve those goals, and be assured in that achievement. Note that Tulip and Junior do NOT fall dotingly in love with the baby and automatically become a family. The wolves’ are seen as in the wrong for this behavior, and so is Jasper, who realizes his ultimate mistake (falling in love with a baby just because its “cute”) and resolves to return to just finishing his job.

This is Junior’s ultimate lesson, which he recites (ironically, when he recontextualizes Cornerstore’s slogan into a personal mandate) when he finds himself in a factory filled with babies and an assortment of unemployed storks around him. This is also Storks’ weakest moment; its third act is lost in its perfunctory need to create an over-the-top climactic moment (if you watch carefully, Tulip and Junior don’t do anything but watch the chaos unfold in the entire sequence). A friend of mine commented on the need to kill off (and, for all intents and purposes, he is killed off) Hunter when he just wanted to protect his company, and he has a point. Turning Hunter, an antagonist who just had a strict corporate/capitalist mandate, into an out-and-out villain was a mistake, but you definitely get the sense that even the filmmakers felt ambivalent about it. (This more or less is notable in their approach to Toady, whose antagonism and motivations are hilariously, and purposely, unclear; Tulip and Junior barely grasp his role in the chaos that unfolded in the end).

Storks is infinitely more interested in the kind of silly, cartoonish world it created and the lost, confused characters who inhabit it, who open up to their insecurities through funny voices and dumb expressions, but whose insecurities are still present and significant. In its final moments, Storks showcases the myriad of families, and family types, who embrace their babies (many of whom could indeed never get babies the traditional way, something a “woke” sequel could really delve into?). It provides Tulip her rightful family, but more importantly, it gives her a sense of identity (family) and purpose (delivery of the baby). It also provides Junior a sense of purpose (embracing baby delivery at Cornerstore.com) as well as identity (Junior was never as lost in knowing who he was as Tulip was, but establishing a personal connection with her, and her family, does seem to provide him a level of peace he never knew he lacked). As heartwarming it was to see Tulip and Junior embraced by Tulip’s family, it was also right, perhaps even more so, to see the two of them nod at each other confidently in the workplace, confident in their new role.

Why Bunnicula Is One of 2016’s Best Animated Debuts

Posted by kjohnson1585 in Animation, Television, Uncategorized, Writing on April 12, 2017

In 2016, Cartoon Network attempted to rebrand Boomerang, its sister channel that airs an assortment of classic cartoons and nostalgic ’90s productions. Along with the newly-fashioned logo, Boomerang broadcasted three new shows: Be Cool, Scooby-Doo, Wabbit, and Bunnicula. Be Cool, Scooby-Doo, which I reviewed here, was clearly meant to be the flagship show to capture new viewers for the “new” channel. Scooby-Doo fans are a quiet but dedicated bunch, and their eyeballs would help steer the channel in positive direction. Wabbit, the newest iteration of the Looney Tunes franchise, was essentially the version of what The Looney Tunes Show was originally meant to be. Its use of classic characters and short-length format would fit perfectly between old and new shows, and meant to appeal to those (dwindling) fans as well. Then there was Bunnicula – a curious show based on the classic book series of the same name. There wasn’t much of a big push for this show, certainly not in a way that would scream “check out the new Boomerang!” It’s hard to say what role Bunnicula was supposed to be in the overall rebrand, but it’s clear it wasn’t supported but CN bigwigs.

The rebrand was, for all intents and purposes, a failure. Be Cool, Scooby-Doo brought in its fans but they weren’t sitting around for the overall Boomerang change-over. Wabbit struggled to grasp the kind of manic energy that the best Looney Tunes works could muster; its skinny designs and muted color palette didn’t help much either. And, again, there was Bunnicula. The off-kilter cartoon by Jessica Borutski and Maxwell Atoms had a less-than-average pilot and made an strange choice in casting Sean Austin to voice Chester and Chris Kattan to voice Bunnicula – the latter of whom barely speaks any actual words. Using non-typical voice actors to voice cartoon characters is a fairly dangerous move, and that pilot suggested some basic, cartoonish antics – Tom & Jerry-level slapstick within a soft-horror atmosphere. Nothing suggested it was worth watching, in other words. But it’s now clear that this was all set-up. Bunnicula quietly uses its pilot and subsequent episodes to build a genuinely creepy and funny show that manages to depict three specifically-cliched characters with layers of complexity that become more and more noticeable over the series’ run.

[As part of a sudden new approach to Boomerang, a number of episodes have been placed on its online streaming site, which requires a paid subscription. Time will tell if this will be more effective than their cable rebrand attempt.]

It’s common for characters in cartoons to exhibit various stock traits that are utilized to incite conflicts that lead to comedic set pieces or low-key dramatic beats. The story usually take precedent, in which characters’ personalities and behaviors butt up against other characters’ personalities and behaviors, or some broadly ludicrous situation. The sillier the cartoon, the more exaggerated those traits will be. Traits may be slightly adjusted as episodes go along, but there’s rarely much examination on why certain characters are the way they are. The nerd kid is the nerd kid. The spunky gal will always be the spunky gal. The stupid goofball is, unfortunately, the stupid goofball, day in and day out. Bunnicula is different. It definitely exhibits the exaggerated energy of a silly cartoon, but it puts more careful consideration into its characters (particularly Chester and Bunnicula, but Harold as well) than you might expect. Bunnicula, on the surface, is about a scaredy-cat, a dumb dog, and a carefree demon bunny getting involved with wacky situations. Bubbling underneath is the story of a family of pets with strong, personal, problematic traits that they gradually work through so as to try and be there for not only each other, but for their owner as well.

Bunnicula is a far cry from its original source. They’re not old-hat pets owned by a boy and his family, but semi-new pets procured by a young, tomboy-ish girl named Mina and her father. Chester, Harold, and Bunnicula know each other of sorts, but it feels like they’re still getting the hang of being around each other, and around Mina. They clearly love her, but they’re working through the particulars of what that entails, particularly Bunnicula. They’re also working through how they exactly feel about each other, as their comic traits are used to mask or distract from their truer feelings for each other. All of this takes place within a New Orleans locale (an inspired setting to be sure), filled with various kid-friendly (but still creepy) horrors and monsters. Yet in the midst of all that, these three pets seem to grow… well, if not more fond of each other, at least more understanding of each other and themselves. They incrementally discover that their base traits are something that they need to work on and work through – not just specific traits for the comedic sake of it. (Even in the chaos of the pilot, “Mumkey Business,” it’s clear that Bunnicula expresses a slight change of heart towards Mina, upon realizing his causal associations with dangerous creatures could harm her.)

Bunnicula, at the base level, thrives on an old-school cartoon charm and sensibility. Molded off the basic premises of Hanna-Barbara cartoons (particularly Tom & Jerry), Bunnicula visually and narratively exhibits an artistic design that would be at home in the ’40s and ’50s. Harold is a clear homage to Scooby-Doo himself. The characters’ hands can transform from animal paws to actual gripping fingers in an instant. Characters pull items out of nowhere from behind their backs and possess pockets in their fur whenever they need them. Physical, violent humor is the norm, if not as extreme as those classic shorts were. It’s righteously self-aware. Chester, Harold, and Bunnicula function on a single trait that instigates, or mitigates, the plot. It does Wabbit better than Wabbit does Wabbit.

Yet unlike most classic shorts, its three leads are driven, at a base level, by genuine love. It’s probably the first cartoon of its type where characters actually say the words “I love you” to each other, even if after the stress of a crazy story. It’s a show where its cast deeply care about each other, even if they have to be reminded of it. Their endgame protection of Mina from the disturbing creatures around them keeps them successfully grounded, even when their intrinsic traits push them to their extremes. Bunnicula himself is wildly amused by these horrible creatures, but needs to reminded of their danger to Mina (and by proxy, Chester and Harold). Eventually, he calms down. Harold is less complex – a simple dog who often gets the buffoonish jokes, but he also is more emotionally open and honest. He’s the first one to express love for others and to whom Bunnicula and Chester most likely express their affections. (This is most notable in the episode entitled “Bearshee,” where Harold plays diplomat between the easily scared cat and a confused, frightened ursine specter.)

Then there’s Chester.

Using Sean Austin as the voice for Chester in retrospect was a good idea. Austin captures that over-the-top energy that’s often required from the character, but he also manages to nail a sad vulnerability in the character that becomes clearer in each episode. Chester’s fears are both exaggerated and sensible, but also weirdly indicative of something, perhaps, darker and lonely. (Nothing exemplifies this more than his final speech in “Chester’s Shop of Horrors.”) He often desires to be a human (“Curse of the Weredude,” “Nevermoar”), for example, and it’s tricky to tell if it’s just to escape being a cat, escape being afraid all the time, or to be respected for his “true” self. (Arguably, it’s all three.) He desires the simple, finer things: a good crossword puzzle, beat poetry, riddles, sci-fi. He’s also kind of a control freak, but it’s not driven by an inflated sense of self-worth – not entirely. It’s really to have some sense of control over his own life, in a world of random terrors and horrors that come to afflict him and his world (darkly captured at the end of “Puzzle Madness”). At times he will go overboard, torturing Bunnicula or deeply believing he deserves good luck at the expense of others’ bad luck. Chester’s fears and insecurities aren’t wrong, His reactions to them often are, but also, he can’t help it.

Chester, Bunnicula, and Harold are who they are, and Bunnicula takes care (for the most part) to make sure their actions and attitudes make sense, that even when they butt up against each other, that it’s all part of a “larger” struggle to find common cause or affection among each other. Bunnicula shows that that kind of emotional camaraderie is a hard thing to do. There’s no grand epiphany – partly because if there was, there’d be no show. But there is a gradual, tedious, comical struggle for the characters to accept each other, and their flaws, and their insanely divergent personalities. Bunnicula is about how love trumps all, even within the context of a wacky cartoon, but it also shows how tricky it is to let that love win out, especially towards those who represent things you don’t even stand for. There’s real affection between the characters, but it’s hard for them to see it, and the show somehow makes it fun to see them try.