Buzzfeed got the animation world talking quite a bit with its recent article “Inside the Persistent Boys Club of Animation.” And while it fits perfectly within the contemporary, aggressive call for more women (and PoC) creatives in the entertainment business – a call I agree with one hundred percent – it’s Lange’s exploration of how certain genders depict certain types of narratives that has my interest piqued. She writes:

And that difference shows up on our screens. According to a 2012 study from the Geena Davis Institute, female characters made up 31% of speaking characters in primetime children’s shows — less than a third. Only 19% of children’s TV shows had an approximately equal number of male and female characters.

Later:

And this mentality is drilled into women studying animation. In a class at CalArts, Cotugno recalled, an instructor lectured on the difference between “feminine” and “masculine” story elements — “which is a little hard to describe, mostly because it’s fucking bullshit,” she said. Elements such as linear storytelling and big external stakes were “for men,” while relationships and emotional storylines were “for women.”

The whole thing is a must-read, but those two paragraphs struck me because it clarified a lot of thoughts I had about how women characters function in cartoons. As you can tell, I watch a lot of animated “stuff,” and what’s weird is how, overall, male characters are fairly developed from the start while women characters tend to fluctuate. This is in extremely broad terms, but part of me wonders if the kinds of stakes that we’ve inadvertently gendered is a bigger issue than just poor, outdated teaching ideas. It’s a top-down problem worth exploring in deeper detail.

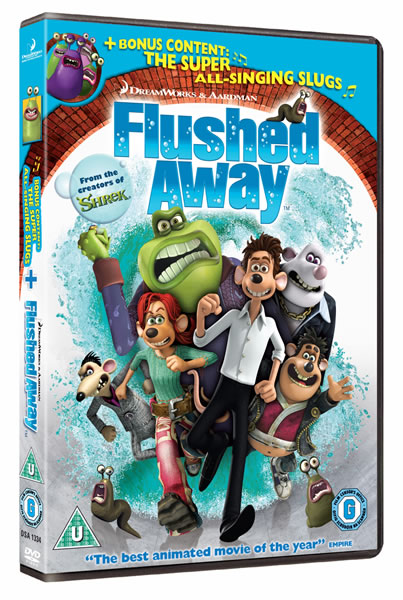

A few weeks ago, I watched Flushed Away, an Aardman/Dreamworks collaboration that did mediocre at the box office, so as to assure that Aardman and Dreamworks would never work together again. It was a film that garnered mixed to poor reviews, but with my current run to catch up on animated films, I thought I’d give it a go, with the requisite that I would Twitter rant about its flaws. And while it was flawed, I was struck by how fascinating the “secondary” character, Rita, was. Rita was an extremely strong, well-developed presence, much more than Roddy, the titular main character. She was voiced by an extremely game Kate Winslet, and had the tenacity of Lara Croft with a warm, engaging emotional appeal like Pearl from the early episodes of Steven Universe. With a few tweaks, Flushed Away could’ve been an precursor to Mad Max: Fury Road – a generic film masking a strong, almost-feminist bent, in which Rita was the real star and Roddy, at best, an annoying sidekick. I can’t tell if it was Dreamworks or Aardman who missed that narrative, but it goes to how we perceive certain narratives and gendered character roles within a piece of entertainment.

I’m not sure how anyone, within the pre-production period of a film, not look at the development of Rita and recognize that she is the star, full stop. She possesses the “big external stakes” and the main thrust of the film is built upon her goals. Yet placing Roddy as the film’s lead is just part of the overall trend with large-stake narratives (he’s front and center on the DVD cover). There are plenty of great female characters, but they feel isolated, the lone feminine figure in weirdly, excessively male-driven worlds. Yet there’s a little bit more going on here, because opening up certain types of characters to the feminine sphere might cause a bit of hand-wringing. In the past 35 years, how many villains, or even antagonists, in films have been female who aren’t mothers? And what about the henchmen?

(The role of henchmen is worthy of a talk of its own. From second-in-commands to the lowly grunts, being a henchmen is a seriously male-driven occupation. How much of this is Standard and Practices, though? How much of this is the overall fear of placing female characters in positions that is primarily set up for bumbling and red-shirting? Because animation has become a medium driven to appeal to kids, the fear is that placing women in roles that usually get abused would be disrespectful and cause kids to follow suit, but that’s damaging to both boys and girls, since it ignore girls completely as well as encourages that kind of disrespect among boys. But I digress.)

One of the most important aspects of the early Disney Afternoon cartoons was its general focus on appealing to a broad, mixed fanbase. Both The Wuzzles and Gummi Bears clearly were looking to appeal to both boys and girls, but the focus shifted as Ducktales hit the airwaves. The shows that came after – Rescue Rangers, TaleSpin, Darwking Duck – had enough content to keep young women hooked, but they were mostly the fare of boys. In addition, the grouping dynamics of the primary cast of cartoons shifted. Girl-to-boy ratios went from 2:3 to 1:3; if a show present a group of mixed-gendered characters as the show’s leads, it has never provided more girls characters than boys. Mostly all kids networks mimicked this, despite hit shows like The Powerpuff Girls showing the potential of female character-driven shows. And really, not since Hey Arnold! have a show really explored a rich, varied group dynamic.

It’s clear that gendering narratives is both harmful and lazy. But what is insidious is how ingrained this idea has become. Not only are certain “types” of stories have to be told from the perspective of boy characters, but the minute details of those stories have to fit certain parameters. There’s very little focus on emotions or vulnerability, although that is getting better: Wander (Wander Over Yonder), Steven (Steven Universe), and Gumball (The Amazing World of Gumball) are much more prone to wearing their emotions on their sleeves, and acknowledging that those explicit feelings are valid.

Female characters are getting better as well. From the Mane6 of My Little Pony to the spunky silliness of Star from Star Vs. The Forces of Evil, TV animators are not only allowing women characters to star as leads, but to engage in their audacious adventures while also letting their emotions out for all to see. The wall limiting what types of stories one can tell with gendered characters is changing, albeit slowly, without necessarily falling into the kind of traps that hurt other narrative forms – restructuring the “Strong Female Character” as “Masculinized Female,” for example.

The biggest problem seems to be that in our attempts to push down gendered limits in entertainment, we’re pushing more and more into segregated content. Strong, singular leads are great, but shows that demand broad, mixed casts struggle intermixing gendered characters, from the testosterone-driven brotherhood that is the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, to the female-coded Gems of Steven Universe. Which, inherently, is fine, but it hinders creative insight into how a full group of boys and girls can manage a situation and keep true to themselves. It’s a top-down problem, again – there’s an upcoming all-female Ghostbusters and an all-male one coming soon. There’s an all-female Transformers on the way, along with an all female DC-superheroes series coming as well. Genevieve Koski over the (sadly now-defunct) wrote about the problem with the “distaff counterpart,” but at the level of younger viewers, it implies that not only are the two genders markedly different, but that they can’t even interact without some kind of problematic “Mars/Venus” dilemma, as if two different genders thrive in two different parallel universes.

These ideas, taught to us as kids, have become de facto lessons, that the decision of creating a certain character male of female automatically define the basic beats of a story – beats that cannot embrace multiple genders in any narrative way. An evil force that wants to destroy the world has no ties to male or female characteristics, but more often than not, male characters are the heroes, thematically linked to paternal-leadership-protector themes. For the few women heroes that save the day, they’re linked to more emotional-maternal-caregiver themes. And it’s that core, basic thinking is more troubling than we realize. Thematic resonance is important to all narratives, but not when they’re built on vague stereotypes and gendered segregation.